Bank of Canada decides to Grin and Bear it

The Bank of Canada established an easing bias, expressed worries over the rapid fall in the currency, but was accepting of a weaker trend in the exchange rate. It set out an optimistic set of economic growth forecasts, but delving deeper into their monetary policy report they hang more on a hope and a prayer. The risks appear clearly biased to the downside for their forecasts. We presume the Bank decided not to cut because it feared feeding uncertainty and volatility. As such it may not take much for them to ease policy in coming months. The performance of Poloz was hard to read; he appears to have tried to gloss over the risks and avoid giving any clear guidance. Some may conclude by highlighting the government’s infrastructure spending plans, the Bank might wait for the March budget before considering a rate cut. Perhaps, but this seems to be a bit of a smokescreen to justify inaction at this meeting. The bottom line may be that the currency is adjusting adequately to the weaker oil price and economic outlook and the BoC just wants to stay out of the way. The wide swings in the CAD since the Poloz conference is indicative of the confusing messages delivered by the central bank. We expect CAD to remain under-pressure and highly responsive to oil prices.

The Bank of Canada Grin and Bear it

The Bank of Canada decided to grin and bear it, rather than take-out insurance against the weaker outlook for its economy.

Governor Poloz gave some reasons why they decided not to cut rates on Wednesday, but they were relatively unconvincing. It was probably more about what was not said.

In his opening statement at his press conference, Poloz admitted that, “It is fair to say that our deliberations began with a bias toward further monetary easing.”

He said that decision not to cut reflected:

- the government’s plans for fresh infrastructure expenditure, to be announced in the March budget;

- The significant fall in the CAD exchange rate since the October Monetary Policy Statement. Poloz said; “Let’s remember that it typically takes up to two years for the full effect of the lower [$C] dollar to be felt”; and

- The risk that a rapid further fall in the $C, might trigger a jump in inflation expectations.

But the unspoken reason appears to be – There are a lot of moving parts at the moment, both domestically with the economy coping with opposing forces of lower oil prices and a weaker currency, and the global situation is also up in the air. Best not to spark more uncertainty by admitting the downside risks are much larger and potentially triggering a further sharp fall in the exchange rate just now.

My best guess is that Poloz and his team felt it would be better to demonstrate calm when all around were in a flap over crashing oil prices, fears over Chinese growth, and falling equity prices. The CAD had already fallen sharply over the last month, and was helping offset the fall in oil prices, so it was not necessary for the Bank to cut rates as well. But it was pretty clear from the downward revision to the domestic growth outlook, notwithstanding optimistic assessments for the outlook for US and global growth, that easier monetary settings were appropriate.

In explaining the case for not cutting rates, Poloz said, “we must be mindful of the risk that a further rapid depreciation could push overall inflation higher relatively quickly. Even if this is temporary, it might influence inflation expectations.”

Poloz offered no guide as to the appropriate level of the exchange rate and when asked whether the recent sharp fall was a cause for alarm, he argued it was consistent with the fall in oil prices.

We conclude that the BoC has no qualms with further declines in the CAD, especially if they occur in response to weaker oil prices, but would prefer them to happen more gradually than seen in recent weeks.

One thing that comes through in the statements on Wednesday, is that the Bank of Canada has adopted the best case scenario for its own, the USA and world economies’. It presumes the weak Q4 growth at home and the USA were temporary hiccups. I guess if you are not cutting rates, you have to present the best case scenario to justify it. You might say the Bank put lipstick on this pig in its opening remarks. But delving deeper in the Monetary Policy Report reveals a lot more of the muck in the sty.

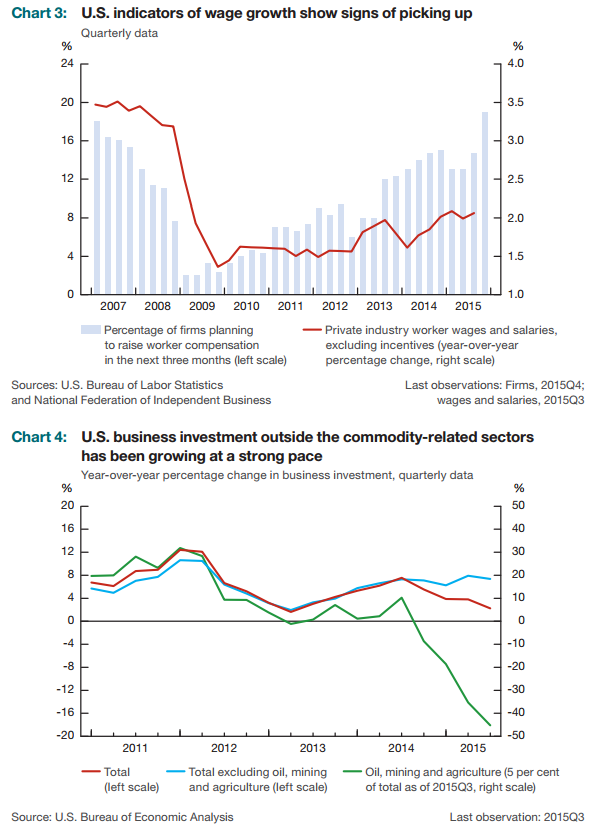

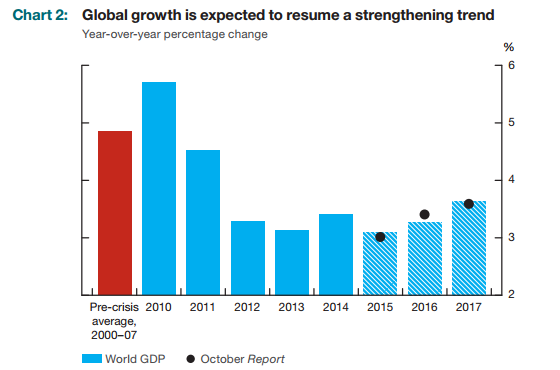

Optimistic base case for the USA and Global Economy

As far as the USA economy goes, The Bank of Canada would have you believe it is all rosy. Just ignore the weak Q4 as an aberration. It said, “Recent data indicate a softening for the fourth quarter that is not expected to persist, given strong underlying fundamentals. Labour income has benefited from robust employment gains, which averaged 221,000 per month over 2015. Consumer confidence has hovered near post-recession highs. Responses to business surveys suggest that a growing number of firms plan to raise wages over the next three months. Improving labour income and lower gasoline prices have supported private domestic demand, as reflected in near-record-high vehicle sales, robust residential construction and strong business investment outside the commodity-related sectors.”

“The softness in the fourth quarter of 2015 reflects, in part, the effects of temporary factors (e.g., a sharp weather-related decline in utilities consumption, new mortgage regulations) as well as slower growth in some areas of the economy that had been strong in the first three quarters of the year.

“The Bank expects the U.S. economy to grow at close to 2 1/2 per cent over 2016 and 2017, with private domestic demand buttressed by the improving labour market, low gasoline prices and still-low interest rates. The headwinds from the global economy are expected to diminish over the projection horizon.”

However, the bank did admit that demand from USA had not been, and may not be, all it’s cracked up to be. The Bank said, “While lower oil prices are providing some boost to consumption, recent data suggest that consumers are saving more of their income gains than expected. Lower commodity prices are also expected to lead to even weaker U.S. investment in the oil and mining sectors during 2016, a factor that is significant for Canadian exports.”

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)

Optimistic Base Case for the Canadian Economy

For its domestic economy there is no getting around the weak Q4, and the drag expected from the further hit to the energy sector from recent oil price falls. As such, growth in 2016 has been revised down and the time frame for closing the output gap pushed further out until end-2017.

But, again optimistically, the Bank projects growth in Canada rebounds to above potential in Q2-2016. It said, “The contraction of investment is expected to end around the middle of 2016. In the second quarter, real GDP growth is projected to begin to exceed potential growth, leading to a narrowing of the output gap.”

From there it projects a steady recovery; it said, “Real GDP growth is expected to strengthen gradually through the projection horizon, with fourth-quarter-over-fourth-quarter growth of about 2 per cent in 2016 and about 2 1/2 per cent in 2017.”

It said “The growth trajectory reflects the ongoing adjustment, with the contraction in the resource sector waning and economic activity in the non-resource sector gaining traction. In view of the extraordinary uncertainty, in the Bank’s base-case projection, the Canadian economy is expected to return to potential later than anticipated in the October Report, around the end of 2017.”

Needless to say, there are substantial risks around the timing of stabilization in the resources sector and the spill over this may yet have on the wider economy. The bank does at least admit to “extraordinary uncertainty”.

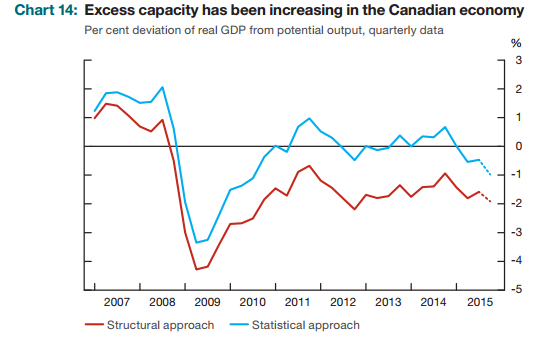

A Hope and a Prayer

There does appear to be quite a bit of hope and prayer in this projection. When delving into the Monetary Policy Report the recent data suggest downside risks are considerably higher. Activity and the output gap have recently been moving in the wrong direction.

The Bank said, “Estimates of the Bank’s two measures of the output gap—the structural and statistical approaches—point to material and increasing excess capacity in the Canadian economy through 2015

Overall, the Bank judges that the amount of excess capacity remained material in the fourth quarter of 2015, between 3/4 and 1 3/4 per cent.

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)

The Bank said, “Labour market data also indicate continued slack, and there is little evidence of wage pressures. Similarly, the Bank’s winter Business Outlook Survey reported that the incidence of labour shortages remains low and their intensity continues to trend downward.”

And further, “Employment growth in late 2015 was more modest than the relatively strong performance registered in the first half of the year, suggesting that labour market conditions could be softening, in part as a result of spillovers from the resource sector that are increasingly weighing on the rest of the economy.”

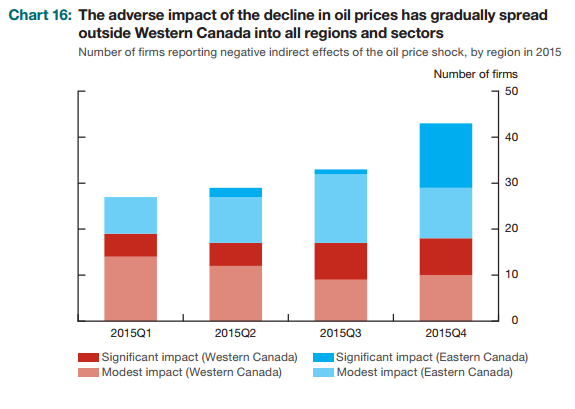

The chart below from the statement also points to bigger downside risks to the Q2 bounce back theory. The impact of weaker oil prices is spreading beyond the main oil producing regions. More companies are reporting adverse effects.

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)

Major risks in Energy Sector

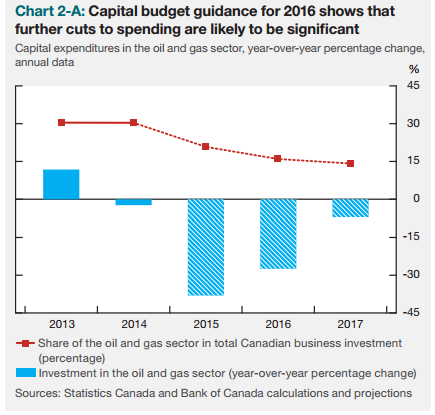

In his press conference, Poloz made a virtue of the fact that energy companies had not significantly further revised down their investment plans for 2016 since the October policy statement. However, revise them down they did, and the commentary around this suggests the risks are biased towards a deeper and more prolonged down turn.

“In light of the challenging environment, firms cut capital spending by about 40 per cent in 2015. Recent discussions with energy firms indicate that spending would be cut by roughly 25 per cent in 2016 (compared with the 20 per cent cut anticipated for 2016 in October) should WTI prices remain close to current levels.”

“Even at prices between US$40 and US$50 for WTI, many energy executives view the current composition of the industry as unsustainable.”

“As the industry reshapes itself to cope with low oil prices, the necessary structural adjustments will require more fundamental changes to operations and could be more profound than the already difficult adjustments made in 2015.”

It further said, “It is important to note that currently assumed prices for oil are approaching break-even prices on a cash flow (i.e., average variable cost) basis for many producers. As a result, there are greater downside than upside risks to production and investment stemming from oil price movements.

“Some firms have indicated that if prices were to fall further, threshold effects would occur. A sustained price increase of a given amount might not have a material impact on the investment and production decisions of firms; however, a sustained price decrease of the same amount could force some firms to cease operations, triggering sharp falls in production, investment and employment, and lead to expectations of more consolidation in the industry.”

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)

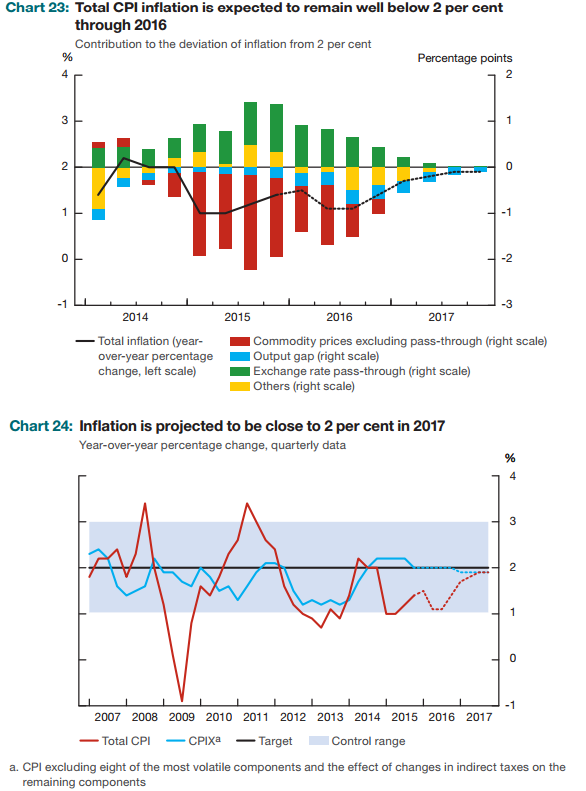

Inflation outlook balanced

The bank is forecasting core inflation remaining close to its 2-percetn target. It projects the pass-through from a lower exchange rate to higher inflation to be balanced by the disinflationary effects of economic slack.

In his opening remarks, explaining why the Bank did not cut at this time, Poloz warned of an upside risk to inflation triggered by a rapid further depreciation.

The Monetary Policy report said, “When a large depreciation occurs over a short period, the pass through to prices could be relatively rapid and thus have a greater impact on annual inflation. In such a situation, inflation expectations might increase, posing an upside risk to projected inflation.”

It seems a bit odd, when central bankers in many other parts of the world are worried about falling inflation expectations that the Bank of Canada would obsess about a temporary rise in headline inflation, but there you are.

In any case the main concern appears to be about the pace at which CAD declines. It has probably been a bit rapid of late for the Bank’s comfort.

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)

Government Fiscal Expansion plans

The bank highlighted the government’s plans for fiscal expansion funding infrastructure investment, expected to be announced in March. Of course this helps, but it hard to rely on this to support the economy in its time of need. No matter how shovel ready these projects are, it is practically hard to spend the money. Infrastructure projects by their nature are prolonged affairs, they provide support over a long period. Furthermore, the government is constrained by a weaker budget, undermined by weaker commodity prices and negative income growth in the economy, it is not projecting a massive program here. They have been talking about $C5bn per year.

The Bank of Canada said that, “government infrastructure investment tends to generate broader spillovers to the economy and thus is associated with larger multipliers than other forms of government spending or changes in taxes or transfers. At the same time, infrastructure spending typically involves longer lags between decisions to increase spending and actual expenditures.”

“The Bank has not yet incorporated into its projection the impact of fiscal measures expected in the next federal budget.”

“The drop in commodity prices and its impact on income and wealth will continue to put downward pressure on government revenues. However, overall, fiscal policy in Canada is expected to provide an increasing contribution to economic growth over the projection horizon.”

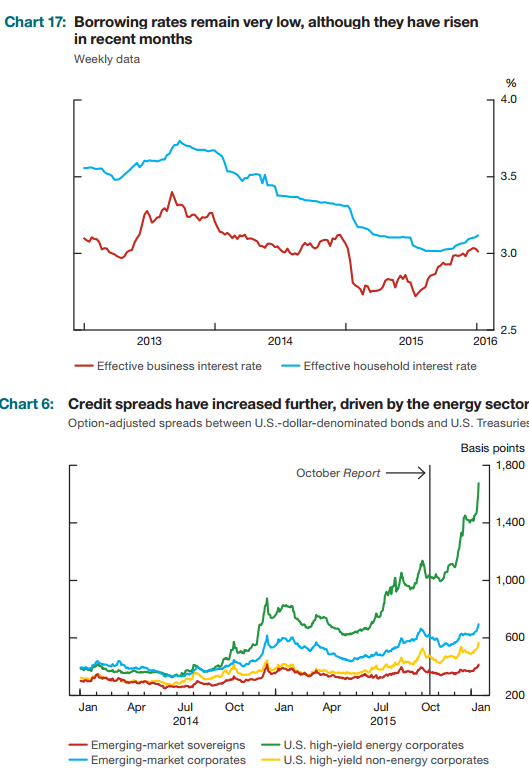

Tighter Credit conditions

The Bank spoke of overall easy monetary conditions, supported by their rate cuts earlier in the year. However they also noted that borrowing costs in the economy had risen lately, indicative of tightening credit conditions.

It said, “For example, yields on 5-year Government of Canada bonds are now roughly 80 basis points below their average level in December 2014. However, bank funding costs have been edging up more recently, prompting some financial institutions to increase mortgage rates by about 5 to 15 basis points. As a result, effective borrowing rates for households, while still low, have risen slightly since the October Report.”

It said, “Credit spreads have widened on high-yield bonds, reflecting a pickup in market volatility and declines in the valuations of riskier assets globally. In particular, issuers of corporate debt in the energy and resource sectors are facing higher borrowing costs and tighter credit conditions, based on responses to the Bank’s Senior Loan Officer Survey for the fourth quarter of 2015.”

The chart below shows business borrowing costs are at their highest level since the beginning of the year, above their levels prior to the most recent BoC rate cut in July. Household mortgage rates also appear close to where they were before the last rate cut, suggesting the July rate cut has been more than nullified.

(charts extracted from the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy Report, January 2016)