Currency Wars before Helicopter Money

Key trends this year include a weaker USD and surprisingly stronger JPY and EUR. This is tending to render the remarkably expansive unconventional monetary policies of the BOJ and ECB ineffective. Japan and the Eurozone have been cajoled by the USA to not engage in competitive currency devaluation and this is worsening the unintended consequences of their policy easing. They fail to recognize that currency depreciation must go hand-in-hand with QE/NIRP policy if it is to work. The consequence of this combination of extraordinary policy easing and strong exchange rates is driving theirs and global yields to record lows. With near zero government bond yields, investors should be fleeing to gold as the alternative store of value. The diminishing power of their QE/NIRP policies is generating much market discussion about helicopter money. But these discussions fail to recognize that any sensible definition of helicopter money goes hand-in-hand with currency devaluation, at least in equal proportion to the inflation generated, and government default. It is clearly a last resort measure that comes after engaging in a currency war. There is a currency war going on; the USA is on the battle ground, while Japan and Germany have been mesmerized into thinking it’s not happening. Overlaying these underlying themes is Brexit fear. This has exacerbated the trend towards lower global bond yields and is pushing up gold. If Britain votes to remain, then there will be a correction in these trends. Whether this is a sufficient circuit breaker remains to be seen. If it votes to leave, it will reinforce these trends and we see potential for an explosive further rally in gold.

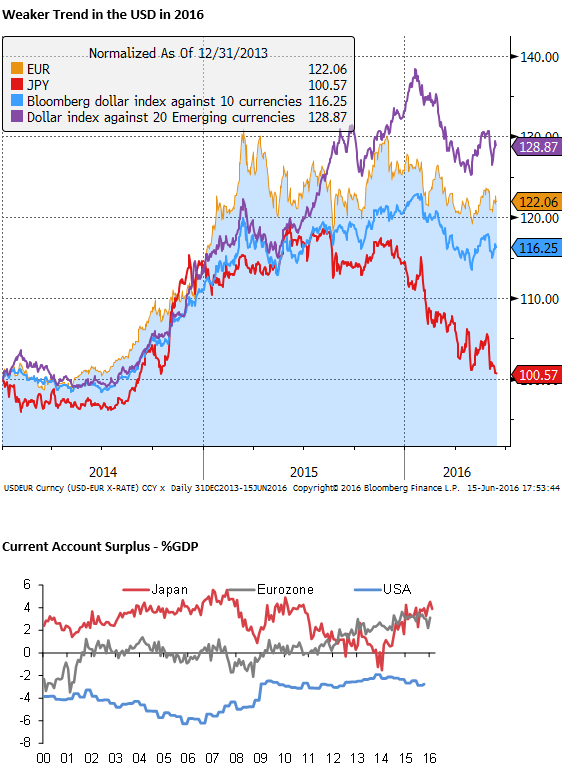

USD on a weaker trend in 2016

The USD has fallen more easily than it has risen this year. The weaker trend in part relates to a turn in the trend for the JPY and a more stable EUR despite further monetary easing by the BoJ and ECB.

Over 2014 and 2015, JPY and EUR were generally considered to be weak currencies as they adjusted to extraordinary monetary policy measures and asset reallocation by global and domestic investors (especially in Japan) towards foreign assets. However, both currencies became historically cheap during a process of asset reallocation and shifts in currency exposure from global investors, households and companies.

With cheaper currency valuations and lower commodity prices both the Eurozone and Japan current account surpluses swelled to relatively high levels historically. Combined with a largely completed major asset and currency allocation realignment, net demand has stabilised for both JPY and EUR to limit further downside potential, notwithstanding extremely accommodative monetary policies that tend to reduce net demand.

Eurozone and Japan stopped targeting weaker exchange rates

Furthermore, both European and Japanese officials, including their government, finance and central bank officials, appear to have agreed that they should no longer overtly pursue weaker exchange rate policies in order to achieve their inflation objectives. A key turning point in global investor opinion appears to have followed the February Shanghai G20 meeting. Since late last year, USA officials increased their pressure on other governments not to pursue exchange rate depreciation in a beggar-thy-neighbor approach to boosting their growth and inflation outlook.

This became more clear as the ECB started to discourage expectations that it might further cut interest rates and shifted the focus of its policy easing towards expanding its quantitative easing to including corporate bonds. And attempting to alleviate bank profitability risks by offering negative rate long term loans to banks provided they expand lending to the non-financial corporate and household sector.

While Japan did engage tentatively in negative interest rate policies, the government failed to intervene to support the JPY at various opportunities as the JPY surged soon after negative rates were introduced; quickly negating any chance the policy may have had to be effective.

Turn in EUR and JPY extended to EM currencies

The fall in the USD against the JPY and EUR to some extent helped turn the trend for emerging and commodity currencies as well, creating a broad declining trend in the USD that may have been self-reinforcing.

Global investor exposure to emerging market and commodity currencies was extremely low early in the year as commodity prices slumped to extraordinary lows and fears over China’s economic direction and financial market stability increased sharply. As such, the market was underweight these currencies and this placed them in a positon to respond positively to even modest improvement in their outlook.

Dovish Fed tone has further weakened the USD

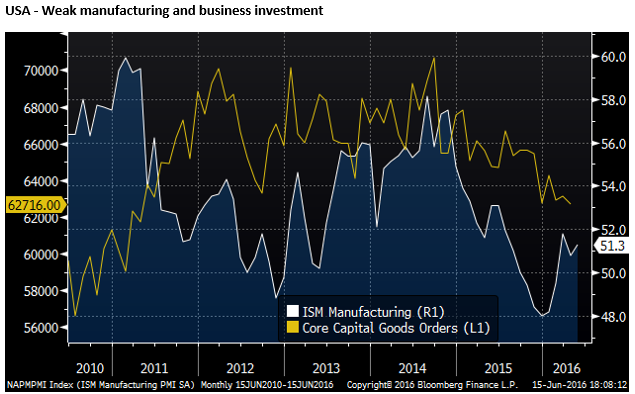

Furthermore, the USD was historically expensive early in the year and its export markets were suffering from the stronger USD for all of 2015. The US energy sector was also in retreat. The combination of weaker export and weaker energy sector contributed to a stalling in the US manufacturing sector and weak business investment.

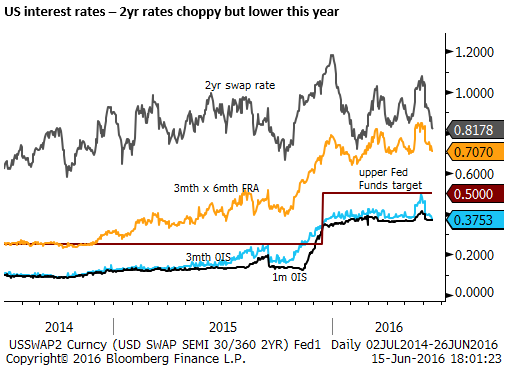

Low interest rates, low energy prices, decent household confidence and a steadily improving housing market continued to support USA growth although it had moderated. Global growth risks had increased significantly over 2015 and into early 2016 and, while the labor market appeared quite resilient, the Fed shifted to a less hawkish stance, considerably lowering its forecast profile for rate hikes over the short and medium term in its March FOMC.

The market, as it has done consistently over recent years, lowered its US rate hike expectations well below that of the Fed. The market moved to view the Fed as potentially permanently delaying its next rate hike, and seeing hikes as highly conditional on improved global growth prospects and/or a weaker USD.

The Fed’s policy stance contributed to the weaker trend in the USD. Combined with stronger net demand for EUR and JPY despite their negative rate policies, and recovering/oversold EM and commodity currencies, the shift in tone by the Fed contributed to a relatively powerful and persistently down-trend in the USD.

The fall in the USD was interrupted recently by some renewed expectation that the Fed may eak out another rate hike this summer. This was possible because the labor market remained resilient and continued to show evidence of tightening and exhibiting some evidence that wage inflation pressure was increasing albeit from a low level. Consumer price inflation also rose more than expected, although by the Fed’s preferred PCE core measure it remains significantly below its 2% target.

The weaker USD this year (albeit still historically high) was probably helping stabilize the US manufacturing sector and contributing to a rebound in oil prices and other commodities, helping stabilize the US oil-patch and global growth expectation. The recovery in emerging market assets and more stable conditions in China also helped stabilize a weak global growth outlook.

Fed nurturing the recovery and was again dovish in June

However, the recovery in US manufacturing is barely noticeable, US business investment remains weak, and some measures of the US services sector, such as the ISM non-manufacturing report have also shown moderating growth. The housing market, however, continues to sustain its solid recovery momentum.

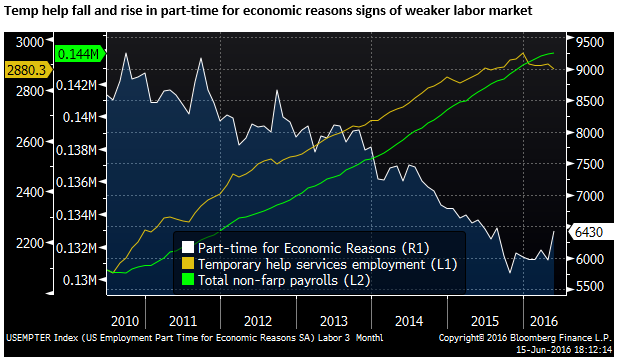

There may have been some lingering and lagging effects on the US economy from weak growth in Q1 spilling over to more recent employment indicators, including the closely watched payrolls report.

However, overall, labor market indicators are mixed with some evidence of strength and tightening, such as weekly unemployment claims, job openings, firmer wages, and lower unemployment rate. And some evidence of weakness, such as lower payrolls growth, weaker temporary help services employment, stalling in quits, stalling in the decline in part-time employment for economic reasons, and lower labor force participation.

The outlook for the labor market is still one of relatively resilience compared to other indicators of activity in the US over the last year, and it suggests that the recovery is continuing and has a reasonable degree of self-sustaining momentum. However, it may also be the case that it is need of more nurturing this year. The Fed has thus become more ambivalent on further rate hikes and it may continue to tread more cautiously in this direction.

This attitude may well contribute to a continuation of a weaker trend in the USD through the course of this year.

However, it is still the case that monetary policies are diverging between the major economies and this should work against a rapid fall in the USD and may eventually return the USD to a stable or rising trend at some point.

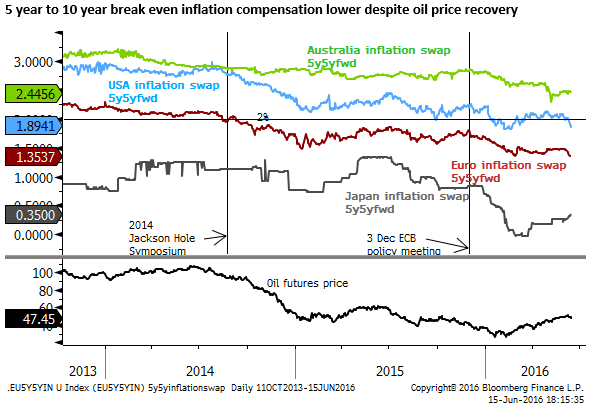

Effectiveness of Extraordinary monetary policy waning

A key development this year is evidence that highly accommodative, increasingly so, policies by the ECB and BoJ have failed to lift inflation expectations in their countries. In fact, despite further policy easing, inflation expectations have fallen and the economic growth outlook has failed to lift much in Europe and has deteriorated in Japan.

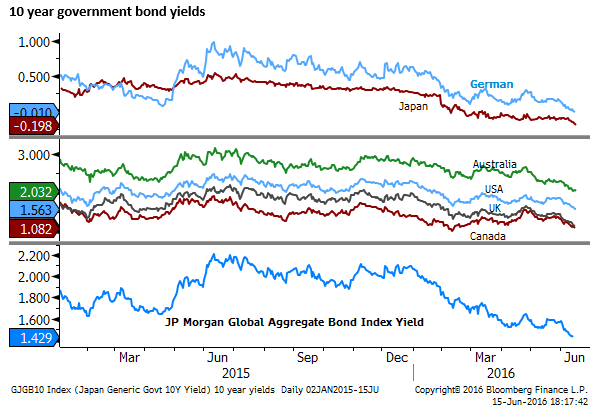

Low and negative government bond yields should boost gold

Both Germany and Japan have negative government bond yields out to at least 10 year maturities. This is a remarkable development. We need to ask why anyone would buy an asset that they are essentially paying to hold; surely cash would be better to hold, at least it doesn’t cost anything.

There is not much reason to hold these bonds at negative yields. Perhaps the only valid reason is for security and the cost it would take to securely warehouse cash. Or, via some game theory logic of the greater fool, investors might buy these bonds expecting yields to fall even further, perhaps on a safe haven flows from other assets (equities and corporate bonds) against the risk of deflation and default.

The demand for negative yielding government bonds only makes sense if investors at least expect the government not to default. Otherwise, even cash starts to seem risky to hold and investors might turn to something hard that has some intrinsic value, or at least is not a debt instrument of any government, such as gold.

Even if the market does not expect default by these governments, gold starts to look like a very good alternative to negative yielding bonds, as it is at least not negative yielding, is easier to store than cash, can be held as futures or ETFs, and thus not a logistical problem to store, offers potential capital gains, and over and above bonds avoids the risk of government default or more adventurous monetary policy measures such as so-called helicopter monetary policy.

ECB and BoJ missing the point of negative rate policies

A reason for negative bond yields across the government curve is that the EUR and JPY exchange rates have strengthened over the last year despite rate cuts. Surely a key reason to cut rates below zero is to drive investors and companies out of holding your currency. Negative rates are arguably a key tool in engaging in competitive currency devaluation. Central banks could intervene to weaken their own currency and actually earn positive carry, making this a profitable enterprise for their country. Theoretically, investors should be running for the hills away from these currencies.

But as mentioned, since the February G20 meeting in particular, it appears that European and Japanese officials have agreed not to engage in competitive devaluations, it suggests that intervention to weaken their currencies in support of their monetary policy actions is off limits. At best, the BoJ has warned it may intervene if the JPY were to rise too rapidly.

By giving up one of the key avenues through which negative rates can work, it has increased the impact of unwanted unintended consequences. Negative rates and falling bond yields has reduced bank profitability, reduced their capacity and desire to lend and weakened their share price, spilling over to under-performing equity markets dampening household, corporate and investor confidence.

Furthermore, with aging demographics, particularly in Japan, households may respond to zero returns on their savings by spending less to preserve capital over their expecting remaining life. This is exactly the opposite effect that the central bank’s hope for.

Younger people and companies may be encouraged by negative and near zero rates to save less and spend more, and borrow to invest, helping boost demand and inflation. But if they are seeing limited investment opportunities that may be dragged down by these negative unintended consequences, they too will be reluctant to spend and invest. This is especially true if deflationary forces are still apparent, discouraging borrowing even if rates are near zero.

As such negative rates in the Eurozone and more so in Japan are not only failing to help, they may be hindering the objective of raising inflation expectations. As such, directly and indirectly they are dragging down their countries bond yields.

Talk of further cutting rates in Japan is thus sending a chill through many policymakers and companies. They fear it is worse than pointless.

Currency Wars a necessary evil

It comes back to the exchange rate policies of these countries. They must not only accept that weak currencies are a necessary component of monetary policy easing, they must actively purse weaker currencies, particularly if they rally in spite of that policy easing, otherwise they risk failing to meet their objectives.

Some will argue that it is not fair to purse weaker exchange rates in pursuit of inflation targets, as this only steals demand from other countries and causes them problems. In a world where global demand is lacking vigor this seems unfair and self-defeating.

However, to not engage in currency war renders domestic monetary policy largely ineffective after some point. Other countries could pressure you to then push harder for fiscal stimulus and structural reform, and Japan has taken more steps in this direction recently, but it remains essential to keep monetary policy working in the right direction.

Currency wars are still effective, because they divert the deflationary problem of the country with the depreciating currency to other countries. If those countries still have room to cut rates or room for fiscal expansion they are pressured to do so, however reluctantly.

If all countries end up in the same deflationary boat, such that no-one is capable of devaluing their currencies anymore and rates everywhere are near zero, then the pressure builds for global coordination to expand fiscal policy or adopt further experiments with combined monetary and fiscal policy and so-called helicopter money.

What is Helicopter Money?

There is not a clearly defined understanding of helicopter money. Back when the Fed, under former Chairman Ben Bernanke, first implemented quantitative easing, purchasing Treasury and Agency bonds, the market referred to him as “Helicopter Ben”. Many thought that this original QE policy was akin to helicopter money.

Expanding the central bank balance sheet, we were taught in economics classes, was a sure fire way to generate inflation. The theory of Milton Friedman, widely accepted, is that inflation is essentially a monetary phenomenon, print more money, chasing the same amount of goods, surely puts up prices. Sounds obvious enough.

In fact in the early days of the Fed’s QE, the USD fell, gold rallied, US Treasury yields rose, because many feared the Fed might unleash uncontrolled inflation.

Perception is so important in the success of any endeavor, including monetary policy. The market expected it to work, so by-in-large it did, the US economy recovered much more quickly and persistently than other troubled major economies. But as mentioned above a weaker USD at the time was a key part of the equation.

Markets have lost faith in the effectiveness of even more intense QE policies now being employed by the BoJ and ECB, and so it goes that they are not working so well.

The experience of Zimbabwe, post-WWI Germany, and a variety of other emerging market economies in the not so distant past, suggests that Milton Friedman was right, inflation will occur if you print enough money. But again we must remember than in past instances of hyper-inflation, exchange rates have collapsed even faster than inflation rose, rendering the currencies worthless.

So inflation without exchange rate depreciation in the context of unfettered central bank money-printing does not happen.

In the current situation in Japan and Eurozone, central banks are expanding their balance sheet at an alarming rate, essentially printing money. But money base is but a fraction of broader definitions of money, and if banks don’t on-lend the money, but hold it on reserve at the central bank, broader definitions of money do not increase, in fact they may decline. If banks take the money and invest it in government bonds, as they used to do before they were negative yielding, then it still does not add to credit growth and broader money in the economy, and thus does little to boost demand.

Now Japanese banks appear to be spreading out the cash that they are chocking on by investing in US Treasuries and other foreign government bonds, but hedging the currency risk via cross-currency swaps, happy with any hint of positive yield to avoid losses.

Demand for credit in the private sector remains relatively weak, corporations are hoarding cash and don’t need to borrow, and even if banks could lend to corporations or households, this increases their risk weighted assets and they are restricted in growing their balance sheet by financial regulators and weak profit growth.

To really emulate the inflationary success of Zimbabwe or the German Weimar Republic, the central banks need to lend more to a wildly spending government; i.e. the government needs to expand fiscal policy and spend directly in the economy to boost demand, and or simply give the money to households via tax cuts.

If they do so with little or no plan or intention to wind back that spending and rebalance the budget in the future, then inflation will result. But of course default risk on government bonds will rise, and the exchange rate will fall as the central bank becomes the only genuine source of demand for these bonds.

Again the key ingredient here is that the exchange rate will fall, and at least as fast as inflation rises. This might be one version of what people refer to as helicopter money.

Some people seem to think helicopter money might just mean combined monetary and fiscal expansion. But that has in a way been done to some degree in the post crisis era. Certainly the BoJ has already tried this, both delaying its second consumption tax hike and providing supplementary spending in late 2014 as the BoJ further expanded its QE.

But if the government presents the fiscal expansion as temporary then it may not work. The presumption in Japan is that they still intend not to default on that debt and sometime in the future everyone must prepare for fiscal tightening to resume. In which case, government spending will mostly only crowd out spending in the private sector.

It does not make sense to expect any form of helicopter money to work without currency depreciation. Combined short term fiscal and monetary policy easing may help kick start demand and get inflation going, but this surely must be accompanied by higher risk of government default, causing yields to rise, the curve to steepen, and currency to depreciate. If the currency does not depreciate this in itself must reflect an expectation that the policy is not genuine and the government is not expected to expand its debt in the long run.

Helicopter monetary policy is a guarantee of government debt default

Money is debt, base money is the liability side of the central bank balance, there is no such thing as printing money without increasing debt. Helicopter money presumably means the bank prints money and the government increases debt, it thus increases the risk of default thus rendering the value of that country’s currency less valuable.

Countries that have engaged in this policy invariably default on debt. As such Helicopter money is essentially guaranteeing that the government defaults.

Even if a country does not actually default on debt, while engaging in helicopter money, this could only be achieved by currency devaluation.

If handled extremely deftly, a country could theoretically engage in helicopter fiscal and monetary expansion, achieve higher nominal GDP growth made-up essentially of just higher inflation, matched by equivalent currency devaluation, and thus maintain a stable debt to GDP ratio.

But of course this is a default of another kind in the sense that the government would be paying back debt in a lower valued currency.

The essential point to come back to here is that helicopter money policy in whatever form you choose to describe it can only work, and really only be called helicopter money policy if it causes exchange rate depreciation. That depreciation will almost certainly be at least as much as the inflation it induces.

Currency War or Helicopter Money? – The choice is clear

For any country, it will always choose to engage in competitive currency devaluation over engaging in helicopter money.

As described above Helicopter money must cause your currency to depreciate, probably alarmingly so, and in a way that no competitive advantage will be achieved. Since inflation will probably rise faster than the currency depreciates, potentially causing the real exchange rate to rise even as the nominal exchange rate falls.

This will probably exacerbate long term structural weakness in your domestic economy and cause other problems, tending undermine real GDP growth and raise unemployment, making it hard to stop once you’ve started. It would be like bringing in cane toads into Australia to control the sugar cane beetle, leaving Australia with an uncontrollable cane tone infestation.

Generating domestic inflation with helicopter money should therefore be the last resort after all else has been tried in the hope that the other problems it creates can be cleaned up later on.

Much better to engage in a currency war first and explain the weak exchange rate policy, just as the Fed essentially did during its QE phase, as simply a consequence of a domestic policy objective, and say we are not responsible for the effect on and choices of other countries.

Global disinflation or Helicopter money – buy gold.

If after the currency war, the world has still not slain the deflationary demon, then presumably the trend goes towards helicopter money. Some or all governments opt for central bank funded government fiscal expansion with the intention of debt default.

I Mean just issue some bonds to the central bank and immediately write them-off, so there is no increase in government debt. The central bank incurs losses, but so what, it doesn’t have any shareholders, it prints the money. The people might be regarded as the shareholders indirectly, and they share the losses incurred by the central bank in the form of being paid less valuable money, in that it buys less goods as inflation rises.

If every country is in the same boat, sure then there is no currency depreciation, but inflation results and the market goes scrambling for any inflation hedge instead of holding money. This includes anything with intrinsic value, gold, property, shares, certainty not fixed income securities.

The missing point though for many that may be advocating helicopter money is that by any sensible definition it is tightly linked to government debt default.

Any country that decides to take this path in isolation will necessarily incur currency devaluation, there is no having your cake and eating it too, you either keep your currency value or you generate inflation.

Back to Reality

While many are now discussing helicopter money as a viable policy choice, the reality is that it is not a path that any government is going to walk down unless all else has failed.

We have quite some distance before we get there, but what we are now seeing is a continuation of the currency war. The USA has subtly taken back leadership in the competitive devaluation stakes.

On the one hand it has placed political and moral pressure on the G20, in particular the G7, not to engage in policies that directly weaken their currencies and to not jaw-bone for a weaker currency. And then on the other, the Fed has stopped raising rates and is openly arguing that weaker exports, the result of a strong USD, is preventing further policy hikes.

The USA has essentially reengineered policy to support a weaker USD trend and the hapless Eurozone and Japanese policy makers have mis-interpreted the situation and have accepted stronger exchange rates that are incapacitating their own QE monetary policies.

Perhaps the ECB and BoJ may even be convinced that because already unconventional monetary policy easing is failing they might have to try helicopter money policy.

Either that or they wake up to their folly and get busy engaging in the currency war again, perhaps by directly intervening in the FX market.

I doubt they will see it this way and they may drift into some form of further simple QE expansion, with some tepid unconvincing fiscal expansion. This could help in turning the tide on inflation, but probably only if their currencies weaken in spite of their lack of direct action.

These policy choices again fuel my enthusiasm for gold. If the USA is winning the currency war this supports gold vs the weaker USD. If the BoJ and ECB are drifting towards more QE and negative rate polices, then this makes their government bond yields even more negative and raises demand for gold as an alternative store of value.

What about Brexit – circuit breaker or catalyst?

Overlaying these underlying themes, driving yields to record lows and weakening the USD are the Brexit vote and ongoing Chinese economic and financial problems.

Brexit could explain some of the recent trends that I have described as a function of currency wars, weak global demand, and ineffective BoJ and ECB monetary policies.

Brexit risks have probably quickened the recent pace of falls in global yields, and made JPY and gold stronger. As such, if on 23 June, Britain votes to remain, we will probably see a correction of some of these trends.

We may well see global risk appetite improve, JPY and gold fall, some renewed expectation that the Fed might raise rates sooner, supporting the USD.

If Brexit fear has been a significant factor driving the broader themes of low yields and stronger JPY and Gold, undermining global growth confidence, and preventing the Fed from hiking, then a vote to remain could render much my concern over underlying weak global growth and ineffective BoJ and ECB monetary policies as obsolete.

However, this remains to be seen. Perhaps the end of Brexit fear will only be a short-lived reprieve. Either way, the Brexit vote is dominating market focus and it will generate significant volatility after the vote.

Should the UK vote to exit, it is likely to reinforce recent trends towards lower global yields and a stronger JPY and gold price. We see potential in fact for an explosive scramble for gold as the market contemplates more adventurous global monetary policy easing and more downward pressure on global yields from already alarmingly low levels.