Trump vs. free trade orthodoxy

Trump trade policy confuses an already muddled FX market. The loud howls from near and far decrying the Trump tariffs may be contributing to an already negative global investor view of the USD. However, most ways you slice it, Trump’s tariffs and broader economic nationalist policies should support the USD, particularly against EM and commodity currencies. In Trump’s view of the world, the USA has been taken advantage of by pursuing the high ground of free trade orthodoxy. If he is right, it makes sense to respond with trade protection even if that generates risks for growth. Most agree that there is global over-production of steel. If so, the US, as the largest steel importer, has the market clout to help address that problem with tariffs. Fears for a negative fallout to other US industries is probably over-blown. Threats of retaliation against the USA may be just that, as most of its trade partners have more to lose than gain if Trump plays hardball and responds in kind.

Surprising AUD resilience

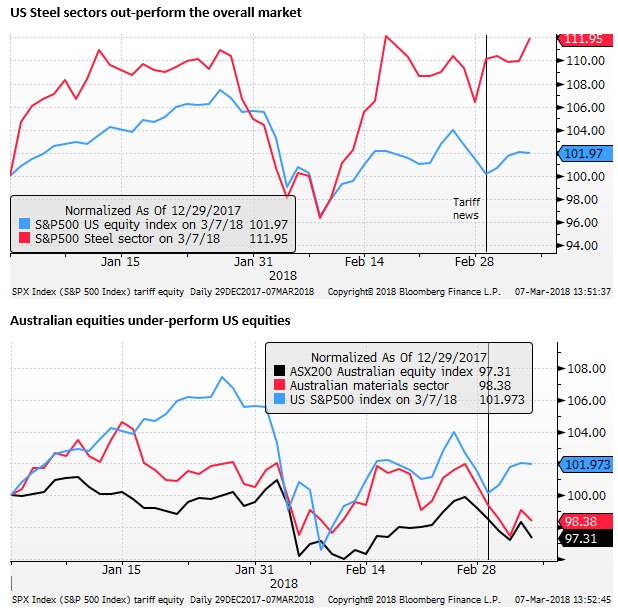

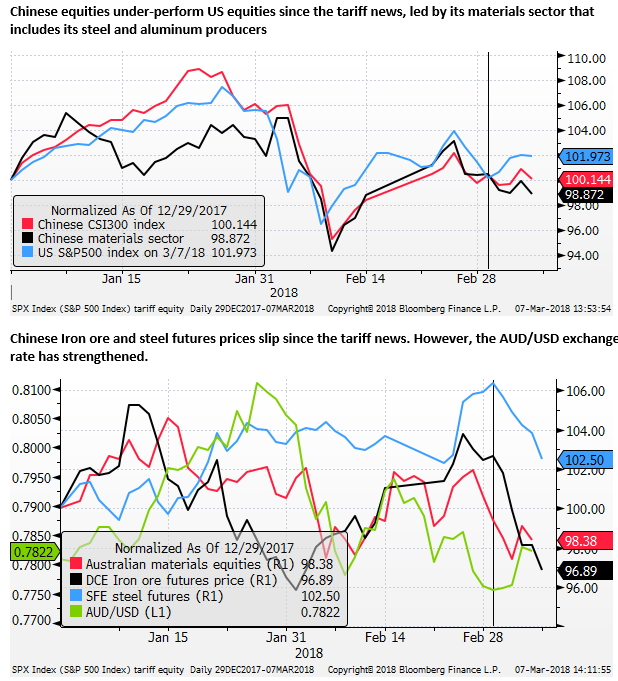

Steel tariffs pose economic risks for steel producers outside of the USA. The principal target of the tariffs is China.

The outcome should be that the US produces more steel, and takes a bigger market share inside the USA. Other steel producers will lose market share in the USA, and receive less return from sales in the USA (after paying the tariff). This is going to increase the fight for market share outside the USA and put downside pressure on steel prices.

The downside risks for steel producers may spillover to commodity (iron ore and met coal) producers. The biggest is Australia that sells most of these commodities to Asian countries that are likely to feel the brunt of the tariff effects.

The uncertainty in the steel industry and lower steel prices pose a downside risk for Australian commodity exports. China, for instance, may respond by accelerating the consolidation in its steel industry, reducing demand for iron ore and coal. As such, the tariffs should place some downward pressure on the AUD.

Perhaps the market is assessing that the impact of the tariffs on global steel markets is not big enough to turn the dial for the AUD. However, the US is the largest import market for steel, and equity and commodity markets have shown some response to the news.

EM and commodity currencies surprisingly resilient to broader trade war risks

Furthermore, the tariffs signal a new tougher phase in the US administration’s approach to foreign trade. Trump has talked tough on trade deals since coming to power. The administration has placed tariffs on washing machines and solar panels, and lumber from Canada. It pulled out of the TPP trade deal in the first days of government, and has initiated a renegotiation of NAFTA, which reportedly is not going well.

Surprisingly, the market seemed to think earlier this week that Trump was going to walk-back on the tariffs as opposition from abroad, his own party and inside his administration became very vocal.

However, Trump has only doubled down on his intent to push forward. This increases the risk of retaliatory action from other countries, followed by further tit-for-tat reaction from the USA.

The evidence that the US is not finished with steel and aluminum tariffs is piling up. Trump’s rhetoric goes far beyond these industries and he is making threating comments towards Asia and European trading partners.

As such, the market should already be building in the risk of a trade war. Equity markets are displaying some risk of this, but it is far from clear that currencies have responded.

Emerging market currencies, particularly those of large exporter nations should be weaker. Furthermore, investors should be reducing their risk appetite, potentially seeing capital outflow from higher yielding and EM assets. This should further undermine emerging market and commodity currencies. However, there has been little evidence of this.

The EUR might be seen as a safe haven as a major reserve currency with a large current account surplus. However, the Eurozone has plenty to lose from a trade war, with a larger share of exports as a percentage of GDP than the US, and a large trade surplus. The market also appears to have amassed a significant net speculative long position in the EUR over the last year, anticipating ECB QE taper. In a period of risk reduction, we might expect position cleansing to weaken the EUR. The EUR has rebounded significantly since the tariff news.

Weak USD trend still pervasive

The currency market has often become divorced from fundamentals over recent years. It has frequently reacted only after the event has been slapped in its face, or even later, rather than building in the risk ahead of the event. As such, we need to be wary of a potential delayed reaction in FX markets, such as a sudden fall in EM and commodity currencies.

The USD has been weak over the last year or two, despite rising US interest rates and yields, so the theories that have gained more credibility in recent times are those that explain a weaker USD.

These include twin deficits, rising inflation expectations, an approaching end of the US tightening cycle (albeit still potentially more than a year away), normalizing monetary policy at the ECB, and approaching in Japan (albeit still probably more than a year away), a revival in capital flows to EM, and political risk in the USA.

There is a building sense that US hegemony and the status of the USD as a reserve currency is in decline.

A recent theory that is gaining traction is that the USD fell during previous US protectionist policy developments and, therefore, it should fall this time as well. The USD fell after former President Bush imposed steel tariffs in 2002.

There may well be some validity to these reasons for a weaker USD, and these may account for the apparent underlying down-trend in the USD over the last year. They may account for why the tariff story is failing to have much impact on currencies.

The trend in markets can be a powerful driver in its own right. You may have been rewarded for latching onto a weaker trend in the USD and trading from the short side. As such, you are likely to stick to this strategy. Those on the other side of the market, often where I have found myself, have tended to lose from this strategy, and have thus become more cautious traders. The trend towards a weaker USD may be washing out, for now, the impact of tariffs and a rising risk of a trade war.

Trade orthodoxy vs. Trump

Another argument that might explain a weaker USD is that the US has come under wide condemnation from near and far for proposing steel and aluminum tariffs.

There is a lot of breathless criticism of the trade policy damaging US industry from most US politicians and commentators.

Whether this criticism is valid or not, it tends to further diminish the hegemony of the USA. The market might expect the world gang up on the US with retaliatory trade restrictions, while promoting more free trade outside the USA. And encourage less use of USD in global finance.

Foreign governments might feel the Trump administration is vulnerable, facing much internal criticism and facing mid-term elections, emboldening them to attack the US with retaliatory trade restrictions.

Is Trump right this time?

The alternative view is that the USA is still a large and significant market for the world’s exporters. In a trade war scenario, other nations have more to lose, and thus their bite will be worse than their bark.

Critics inside the US see the steel tariffs raising costs for a broad array of US manufacturers, reducing their profitably and threatening jobs in other US sectors. However, steel prices may not rise all that much in the US. The tariffs will reduce steel prices abroad. To gain market share inside their own country, US steel producers will aim to undercut prices in steel from abroad; albeit after the tariff is added. The cost increase for US manufacturers, like car producers, may not be all that large.

Furthermore, the US government has recently cut corporate taxes, doing much more to improve profitability for domestic producers, essentially improving their capacity to compete with producers offshore. It seems unlikely that the tariffs will be a big hit to broader manufacturing confidence. The prospect of broader toughening in trade policy may help bolster broader manufacturing confidence.

The Trump argument is that the USA has been too open for free on trade in the past. It has been a champion of the free-trade orthodoxy; that free trade floats all boats. However, Trump argues that this has allowed other nations to take advantage of the USA, exporting freely to the USA while protecting their own industry. The administration is now arguing that its trade policies are fighting fire with fire, they want “fair” and “reciprocal” trade.

In this view of the world, the steel and aluminum tariffs are justified and are aimed at forcing other countries to address their overproduction and remove subsidies.

In this way of looking at it, the USA is forcing other countries to review their policies on protection if they want to trade freely with the USA. This is an example of the US economy using its market clout, its remaining hegemony, to force changes to its advantage.

Many of the issues that the US administration has are with newly industrialised emerging markets. In the earlier stages of their development, major economies may not have worried too much if these EM nations employed protections for their industries. However, the USA administration now feels that protectionism in these nations is creating too much harm to the US economy.

Most other developed nations are arguing for the US to stick with free-trade orthodoxy and if it has disputes to work through the World Trade Organisation. The US administration does not believe this will be effective and is taking a more direct approach.

Free-trade orthodoxy is a high ideal, and indeed a more integrated global trading system would lift global output and should lift all boats. But if there are significant parts of that system that have barriers to trade, attempting to take a bigger share of the pie, then it makes sense for other nations, such as the USA, to introduce their own protections.

Many commentators tend to think that there is an over-supply of steel, and much of it comes from China. There is probably also a national security issue in steel and aluminum that maintaining some domestic production capability is a good thing. This has always been the case, and why this industry has been more subject to protection over a long history. As the largest import market for steel, the USA has the clout and arguably a justification on economic and national security grounds to protect this industry more than any other.

There is widespread criticism that the steel tariffs hurt US allies, more than China, and other more targeted measures should be employed. However, in a global market, it is hard to see how more targeted measures would be effective. In fact, they may even be counterproductive, simply causing more transshipping with little net impact, except more distortion.

The standard response of everyone is free trade good, tariffs bad. But it may not be so cut and dry, and there are reasonable arguments to suggest that this time Trump may be right to challenge the established orthodoxy. A little more economic nationalism might be a better balance in US policy. It’s probably time to stop worrying about sticking to free-trade that boosts global growth, and using US economic power, while it still has some, to ensure it is getting its share of the benefits from global trade.

Steel and aluminum tariffs may be a good place to start. And if a trade war breaks out then so be it; it may shake the global trading system up and improve it over the medium term, making all sides reconsider what barriers and protections they have in place. Trump may be right; the USA might be still in a good place to win a trade war.