Apartment glut fears may have hit the AUD and NZD

The abrupt turnaround in the AUD on Thursday may be indicative of a more erratic FX market this year. But it may also reflect two big risks that continue to lurk in the background – increasing financial risk in China and financial stress emanating from the apartment sector in Australia. The Australian employment data were also significantly weaker, fanning the concerns over under-employment expressed by the RBA in recent statements. Commodity price indicators have been quite supportive for the AUD recently, but apartment sector financial stresses may now be on the footstep of the RBA before the economy has had time to work through the final phase of the mining investment downturn. Australian banks’ are not too heavily exposed to apartment sector problems, but they have tightened credit to the sector. Much less is known about property developers, but they are thought to be highly leveraged and facing significant headwinds. They may prove to be a significant drag on activity and confidence and force the RBA to ease policy more than expected in coming months. The New Zealand property market will not be immune with their banks also tightening credit under orders from head offices in Australia and tough new macroprudential measures introduced since October.

Erratic FX behaviour

On Wednesday, ahead of the Australian employment report, the AUD broke through a key resistance level that may have indicated a sustained and substantial resumption of a rising trend. The gains could be explained by resurgent commodity prices and a more stable outlook for interest rates over the last month or so as the RBA appeared to sound more balanced, seeing the end of the mining investment downturn in sight and prepared to give the economy time to find its feet with reasonable growth in the non-mining sector and somewhat above average surveys of business and consumer confidence.

However, a day later, the AUD dropped sharply, leading falls in the global currency market after a weaker than expected labour market report, setting up a so-called outside range day topping pattern, made where a rising trend ends with a new high and a close below the previous day’s range.

Many have commented on the more erratic nature of the developed country FX market in the last year. The market has a degree of faux liquidity in the new regime since regulation and litigation forced banks out of the business of risk-taking. Spreads and volatility are blowing out around key events. The EUR’s spike after the ECB meeting Thursday, followed by a bigger fall, on what was largely an entirely expected outcome and press conference, is just the latest in a string of such instances over recent months. On a broader scale, we must be very careful in interpreting price signals these days.

In that vein, the most recent up and down in the AUD may say little about its underlying direction. Nevertheless, the failed break higher and subsequent sharp fall may reveal a degree of underlying weakness.

Weak Labour Market

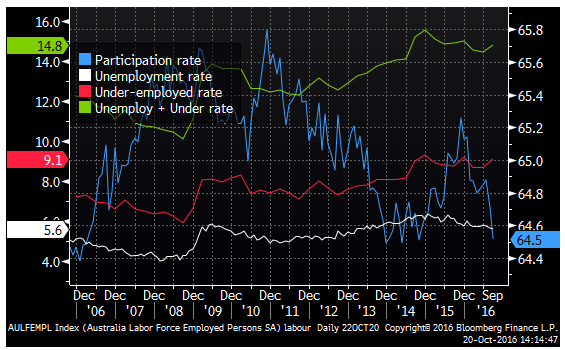

On the face of it, the labour data was not alarmingly weak, total jobs fell -10K and were modestly weaker than expected (+15K). The unemployment rate (5.6%) fell to a low since 2013, better than 5.7% expected.

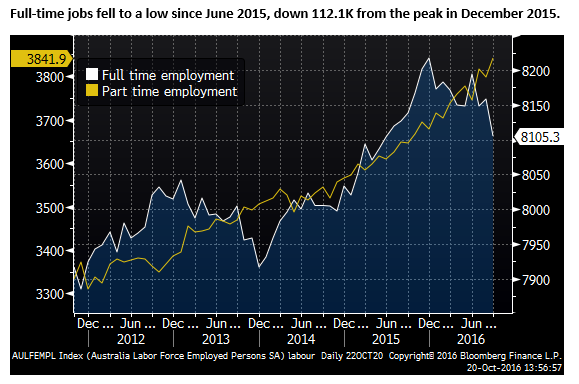

However, the RBA October policy minutes and RBA Governor Lowe speech released on Tuesday this week noted that the RBA was paying more attention to the underlying features of the data revealing more slack in the labour market. They noted a rising measure of under-employment reflected in rising part-time employment and falling full-time employment. The data for September on Thursday suggested this trend accelerated, raising the probability that the RBA may consider further easing policy.

Under-employment (that captures part-time workers that want full-time work and others that are employed below their skill level) has been around 9.1% since Q3-2014, a record high. The sum of under-employment and unemployment is lower in the last 18 months by virtue of a lower unemployment rate, but it rose in Q3, and remains relatively high over a long term comparison. Furthermore, the participation rate has resumed falling in the last two months to be around the low end of its range since 2006, suggesting discouraged workers have left the workforce.

Considering these underlying elements, the data was significantly weaker than expected. It may not be enough to move the RBA to cut rates again. It may prefer to give the economy more time to adjust as the downswing from mining investment runs its course, but it does place more pressure on the RBA to consider a cut, especially if the CPI data next week fail to show underlying inflation stabilizing after its sharp fall in the first half of the year.

Big risk factors may be infecting sentiment, one is China’s worsening financial risks

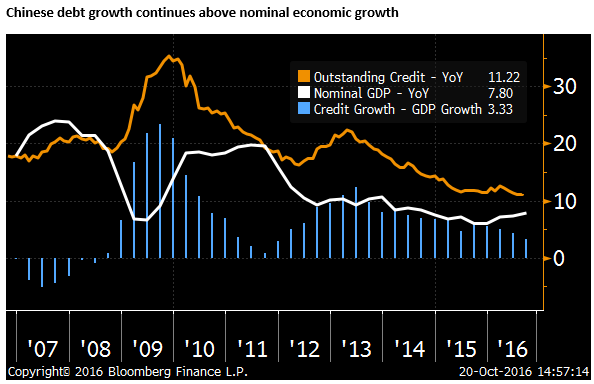

In the meantime, there are two big risk factors that continue to lurk in the background for Australia. One is the sustainability of the Chinese economic recovery. The Chinese economic data released this week continued to show modest recovery underway. However, the strength of that recovery is weak in comparison with the easing in monetary and fiscal policy this year.

The RBA October minutes said, “Members noted that the risks in China associated with the build-up of debt in an environment of slower growth and questions about the sustainability of current policy settings remained a source of concern for economic prospects in China.”

In its Financial Stability Report (FSR) last week, the RBA said, “In China, the level of debt is high and rising despite slower economic growth and signs of excess capacity in some areas; much of the new debt is being extended by the more opaque yet interconnected parts of its financial system. Non-performing loans (NPLs) are increasing, albeit off a relatively low base. While the authorities in China retain levers to support growth, using many of them would likely entail a further increase in debt that could increase the risks to longer-term reform and stability.”

The RBA is certainly not the only one watching with increasing concern over China’s finances. Most private and multilateral institutions are making similar noises. Some researchers are seeing comments in the Chinese financial press suggesting that they are now starting to re-tighten monetary conditions and tighten rules on property investment. It may take several months for these efforts to have an impact, but Chinese economic growth may weaken next year.

Bloomberg analysts’ produced the chart below showing that national debt growth in China (11.2%y/y) continues above nominal GDP growth (7.8%y/y), continually since the global financial crisis in 2009. This suggests debt dynamics that many consider already excessive, continue to deteriorate at a fairly rapid clip.

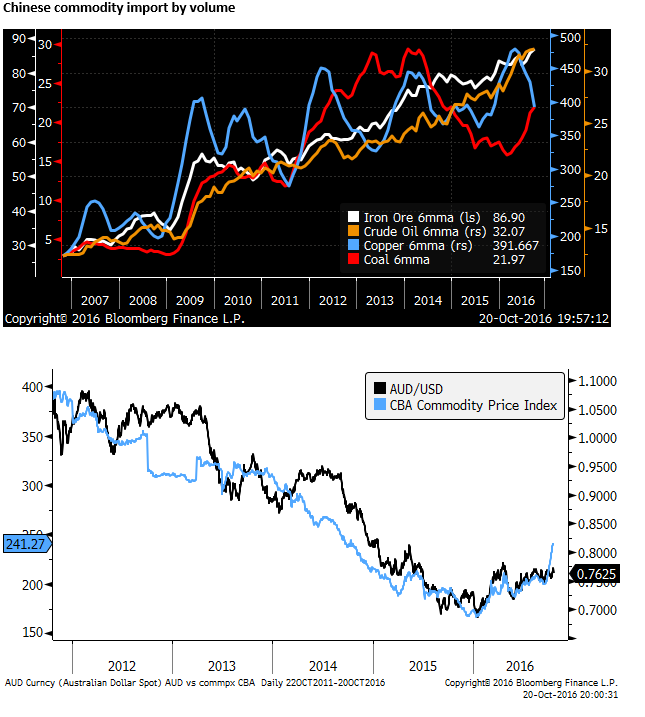

However, at the current time, Australia is benefiting from the recovery in Chinese demand for commodities, and a reduction in its production of these commodities. Lifting both volume and value of Australia’s key exports this year. This should improve the trade balance and fiscal balance. But only so much of this income boost is likely to flow to Australians. Mining companies are unlikely to re-start investment and jobs in this sector appear to still be declining.

Apartment Glut

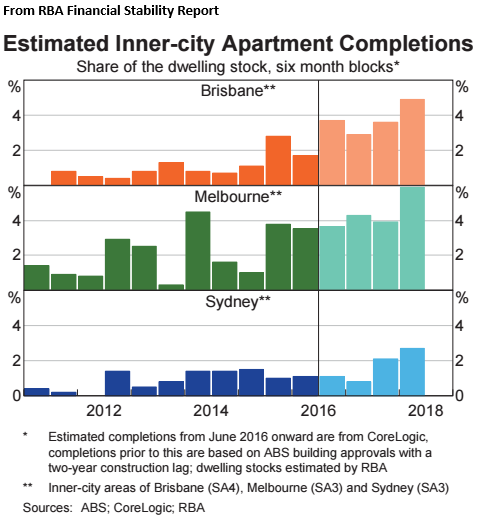

The other big risk factor is a fast approaching over-supply of apartments in Melbourne and Brisbane, to be followed by Sydney a year down the track.

The apartment glut story has been kicking around since the beginning of the year, but it may be coming close to having an impact, perhaps over the next six months.

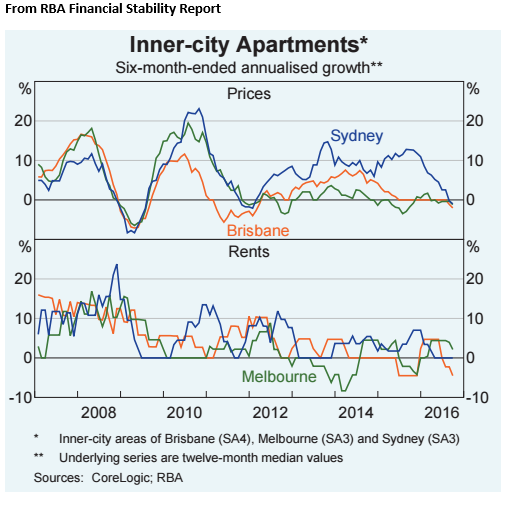

Prices in this sector are now falling, and this is likely to increase settlement risk and may generate a self-perpetuating slide in prices and increase the risk of developer defaults.

RBA rings alarm Bell

The RBA Financial Stability Report spent considerable ink analyzing this problem including a special box on the topic.

In its overview, it said, “Risks around the projected large increases in supply in some inner-city apartment markets are coming to the fore, especially in Brisbane and Melbourne. There are signs that some settlements are taking longer and lending valuations are coming in below their contract price, though settlement failures to date remain low. Banks have recently tightened their serviceability requirements further by restricting lending to borrowers relying on foreign income; this might weigh on demand in some inner-city apartment markets. They have also taken steps to mitigate the associated risks by tightening lending conditions for new property developments. This could also help forestall future oversupply in some inner-city areas.”

We need to keep in mind that when the RBA talks about these issues, they are not going to ring alarm bells too loudly. They want to warn the market without causing a panic for the exits. There are some that see this issue as much more problematic.

As an aside, it is amusing that the RBA’s special box on the issue said the problem is unlikely to be as bad as Spain or Ireland’s post-Global Financial Crisis experience. I’d bloody well hope not!

One of the more alarming voices on this issue is the business reporter Robert Gottleibsen, who has written numerous articles sourcing those close to the industry. While we might caution he is likely to be ringing the alarm bell a lot more vigorously, he does a good job of outlining the detail in how risks could unfold and have wider contagion to the economy.

He accused the RBA in his latest piece of taking a too narrow view on the oversupply.

The RBA FSR estimated that there would be “16,000 [inner-city] completions over the next two years in Melbourne, 12,000 in Brisbane and 10,000 in Sydney. The numbers in Brisbane and Melbourne represent ‘a far larger increase in the dwelling stock than Sydney.”

Gottleibsen quotes Corelogic data from May this year that estimates the number of apartments due for completion in these three cities as over 200,000 over a similar 2-year time frame (perhaps over even a shorter period since the estimate was made in May this year) – more than five times the RBA estimate.

The topic was given considerable further public airing on Thursday with a report from Morgan Stanley Economists led by Daniel Blake and an appearance before parliament by the Chairman of the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority, Wayne Byers.

According to news reports, Morgan Stanley estimates that 160,000 apartments are due for completion by the end of next year, and estimates an around 100,000 national housing over-supply by 2018.

Apartment glut could put a brake on the broader economy – TheAustralian.com.au

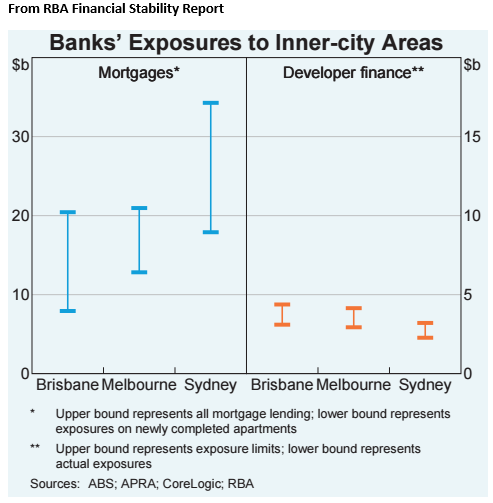

Australian banks’ exposure contained

The RBA estimates that “around 2–5 percent of banks’ total outstanding mortgage lending is to inner-city Brisbane, Melbourne, and Sydney, and this share is likely to grow as the apartments currently under construction are completed. At around $20–30 billion, mortgage exposures are estimated to be larger in Sydney, reflecting Sydney’s higher apartment prices and a greater number of mortgaged dwellings, than in Brisbane and Melbourne where mortgage exposures are estimated at around $10–20 billion in each inner-city area.” (However, Gottliebsen has warned that these figures are a narrow subset of a larger apartment supply problem).

The available data suggest that around one-fifth of banks’ total residential development lending is to these areas. Development exposures are a little larger in Melbourne and Brisbane than in Sydney, due to the greater volume of apartment construction currently underway, though they are each less than $5 billion.”

The RBA analysis suggests that banks’ exposure to potential losses on mortgage or developer defaults are pretty low compared to their overall balance sheets, so we can be pretty comfortable banks are not likely to be even close to being in trouble.

The Chairman of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, Wayne Byers, told parliament that the biggest exposure to the apartment boom has been taken by foreign – principally Asian – banks rather than the Australian banks.

Australian Developers carrying a lot of risk

The RBA admit that it is a much harder task understanding the financial state and exposure of property developers.

Wayne Byers comments suggest a good deal of it is foreign banks funding foreign developers. So less will be known about the state of this finance, but we might conclude that this is more stable than that for Australian developers.

The RBA notes that there is a paucity of data on unlisted developers, who account for a large share of the sector, and foreign developers are becoming increasingly active in Australia. But it appears that debt funding (leverage) of developers is high, suggesting they are a significant source financial stability risk.

Gottleibsen writes that developers rely on off-the-plan pre-sales to secure a bank loan that typically constitutes 40 to 60% of their financing, and the rest of the financing comes from other private investors at a much higher cost of finance. These non-bank lenders pool funds from households and various small institutions. There is very little data on this tier of finance. Gottleibsen notes that banks are also indirectly funding some of this higher risk tier of capital.

Gottleibsen and the RBA analysis indicates that there is a lot of scrambling already underway by developers to keep solvent in a variety of ways. The RBA mentions buyer incentives and discounts, project delays, and in more severe cases, sales of development sites.

Banks have significantly tightened credit to apartment investors. This is increasing the risk of settlement failures. Banks have essentially stopped lending to foreign investors. Gottleibsen notes that many Chinese buyers could pay the 10% deposit, and might be able to pay up to 30% of the purchase price at settlement, but they face difficulty meeting the entire payment due to Chinese government restrictions on capital outflow. They had been relying on being able to borrow from banks in Australia to settle.

Some developers are lending to investors from their own balance sheet, or seeking alternative non-bank sources of funding, at much higher rates.

Gottleibsen makes an important point, that developers are very reluctant to take apartments directly onto their own balance sheet since doing so would take them out of foreign hands. Australian law only allows foreigners to buy newly build property. They would not be allowed buy property if it had been taken onto the developers’ books, as it would become a resale. The property would then have to be sold to Australian investors at a deeper discount.

As the supply of new apartments keeps rising, the scrambling by developers not to be caught holding property with no way to repay their financiers, be it banks or non-bank (shadow) lenders, is likely to become more desperate. This is likely to cause more severe downward pressure on apartment prices and threaten to cause defaults in the sector to spiral.

Potential for broader economic fallout

While there may not be a material risk of a banking crisis, banks can see the rising and substantial risks in this sector, and they have responded by significantly tightening credit conditions for investors and developers. This is certainly going to deepen a developing downturn in the sector, increasing the risk of defaults, intensifying the downward pressure on prices and cause a faster and deeper slowdown in building activity.

It may spill over into weaker house prices more broadly, undermine consumer confidence, cause banks to incrementally tighten credit conditions beyond the inner-city apartment market, and cause a degree of broader economic weakness. It is always difficult to judge the broader economic consequences of a relatively narrow property over-supply. But it clearly opens up the potential for weaker activity that the RBA responds to by further cutting rates.

The RBA note that it is a good thing that banks have tightened up credit conditions for investors and developers, limiting their exposure, and likely averting significant risk of a banking crisis. It also notes that by cutting back funding for developers, the apartment glut may be less than otherwise, delaying projects. However, of course, such actions mean less economic activity and fewer jobs, so it raises the chances of a rate cut.

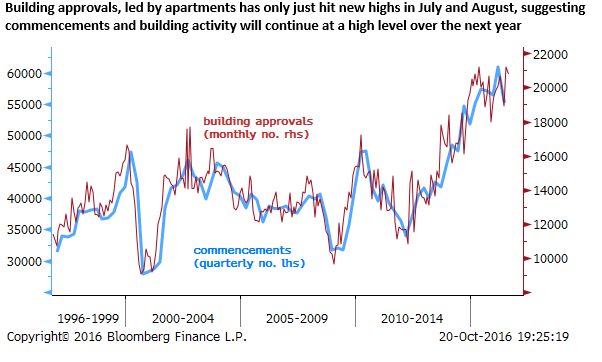

Morgan Stanley Economists wrote that “We believe the growth contribution from the housing boom has already peaked and look for a plateau over 2017 and decline through 2018,”

“New apartment projects should slow sharply as focus turns to settlement of the existing pipeline. For growth, this implies a double-unwind with resources capex, driving our bottom of consensus, 1.9 percent GDP growth forecast for 2017.”

The investment bank contends 200,000 housing-linked jobs are under pressure from the looming standstill in construction, potentially lifting the unemployment rate almost 1 percentage point higher to 6.5 per cent.

“Liaison suggests valuations are consistently below settlement in ex-Sydney markets,” Mr. Blake and his team wrote.

“Non-bank credit is moving to plug the gap at higher interest rates, but we expect some projects will land with the receivers.

“If not contained (this) could set up a negative feedback loop through lower valuations, less credit availability and developer distress, with contagion through unemployment and the hit to household balance sheets.”

The timing of such events is unclear; as shown above, building approvals have only recently made new highs in July/August, Building commencements have moved in lockstep through at least to mid-year. It appears that there remains significant momentum in the building industry over the year ahead. The hard evidence of building activity slowing is yet to show up in the data.

However, financial pressure on developers appears to have been building since early in the year, and we could be on the cusp of deterioration in building activity and meaningful financial stress.

Mixed property market trends

The Australian property market has become more segmented and regionalized. The weakening apartment sector has not yet spilled over significantly to the broader property market in the major cities. In fact, the RBA noted that “housing market activity in Sydney and Melbourne has shown signs of strengthening in recent months. In both cities, price growth has nudged higher of late and auction clearance rates have risen to high levels.”

Furthermore, while banks may have tightened lending to investors in inner-city apartments, they have recently eased lending conditions for better quality mortgage borrowers. The RBA FSR said, “The cost of mortgage finance has declined, and lenders are competing for new customers. Competition for investor loans, in particular, has increased, and banks have recently narrowed the pricing differential between investor and owner-occupier loans. But the tightening of lending standards in recent years has meant that the profile of this new lending is lower risk than it was a year or so ago. For both owner-occupier and investment lending, the share of loans at high loan-to-valuation ratios (LVRs; those greater than 90 per cent) is now around its lowest level since the series began in 2008.”

New Zealand property will not be immune

New Zealand’s property market is a step removed from the apartment glut in Australia. But its property market may well feel some pressure as well. All the main banks in New Zealand are Australian owned.

News reports suggest that Australian banks that have tightened credit conditions for apartment developers and investors in Australia are essentially applying the same conditions across the Tasman as well.

This has been reinforced by a considerable tightening in the RBNZ’s macroprudential rules setting nationwide LVR thresholds. Banks in New Zealand are tightening credit conditions in response to pressure from head offices in Australia and its own banking regulator. There is evidence that housing activity has slowed and this is likely to be a factor taking some additional steam out of the relative hot New Zealand property market.