AUD facing growing headwinds

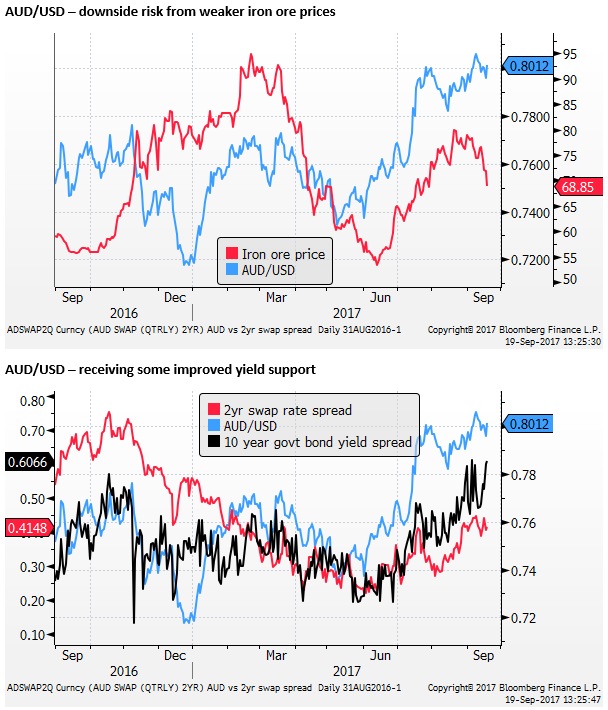

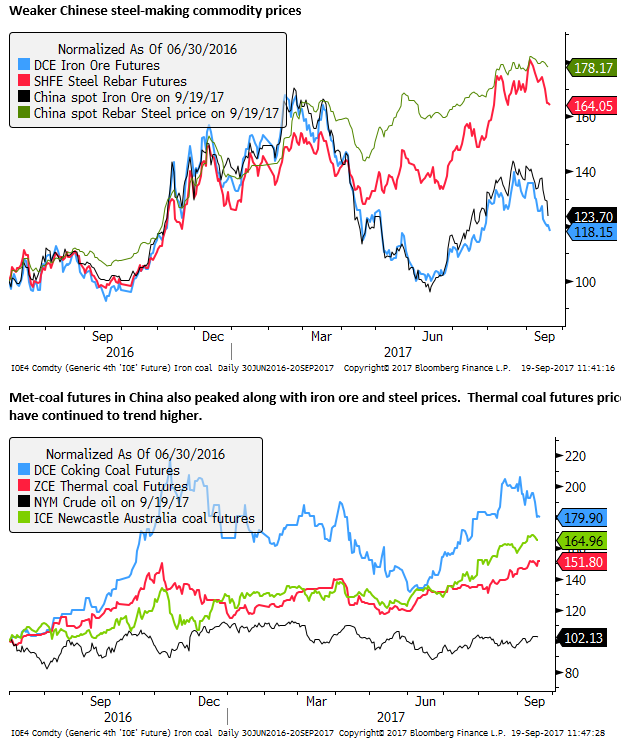

The outlook for the AUD is facing bigger headwinds. Chinese economic growth has slowed in recent months, and iron ore and met-coal prices are weaker over the last month. It appears that steel prices in China have turned over as fixed asset investment slows and steel inventories start to build; albeit from low levels. The RBA minutes released on Tuesday may fuel fear of weaker commodity prices. Its analysis suggests that Chinese long-term steel demand growth has peaked even as more iron ore supply is coming on stream. The RBA is also seeing clearer evidence that the Australian housing market is slowing down and residential construction has peaked. However, credit growth remains steady and household debt is still growing; increasing risks of a homegrown debt problem, even as the RBA frets about China’s debt problem. It’s a complex outlook; employment growth and the investment outlook have improved in Australia. However, compared to improving trends in many major and emerging economies, less leveraged to fixed asset investment in China, the Australian growth outlook is not so special.

Employment growth is not moving the RBA rates outlook

The RBA minutes on Tuesday noted the recent strength in employment growth that continued in the most recent data since the last board meeting. However, there was nothing in this discussion that moved the needle on rates. It did not specifically mention ongoing slack, but the discussion around state trends, steady unemployment rate, and rising participation, suggested no meaningful tightening in the labour market was in sight.

Wages outlook subdued

The RBA also expressed a subdued wage outlook. In particular, it said, “data showed that wage increases in new enterprise bargaining agreements had remained below the average of current agreements.” This even suggests some downward pressure on wages.

The bottom line is no change in the wage outlook. It said, “Members noted that these data were consistent with the Bank’s forecast for growth in wages to remain low for some time, before picking up gradually in response to the strengthening labour market.”

Housing construction peaking, price growth slowing

On housing construction, The RBA noted it is past its peak. It said, “members noted that building approvals had stepped down and the pipeline of residential construction work appeared to have passed its peak.”

Its views on the strength of the housing market were also subdued.

It said that, “In the eastern capital cities, a considerable number of new apartments was scheduled to be completed in the period ahead.”

It said, “In the established housing market, a number of indicators suggested that conditions had eased in Sydney, but to a lesser extent in Melbourne.” It referred to weaker prices, auction clearance rates and auction volumes in Sydney (although not yet in Melbourne). And it said, “Rent increases had remained low in most cities and rents had continued to decline in Perth.”

Contained enthusiasm on investment

The RBA minutes sounded more upbeat on business investment, but contained its enthusiasm. It said developments were “consistent with the Bank’s forecast for growth in non-mining investment to strengthen gradually.”

It said that it expected a moderate further decline in mining investment over the period ahead (2017/18), but “strength in public investment was expected in the subsequent couple of years.” This suggests a subdued few quarters building strength in a year or so for infrastructure investment.

China growth weaker and metals prices falling

On China, the RBA minutes said demand for commodities up to July had been strong. “In China, GDP growth had been a little stronger than expected over the first half of 2017, supported by generally accommodative policy settings. Strong growth in infrastructure investment had continued in July, and further sharp increases in crude steel production and electricity generation had continued to support imports of coal and iron ore from Australia. In the rest of east Asia, a pick-up in export growth as global demand strengthened had underpinned stronger domestic demand.”

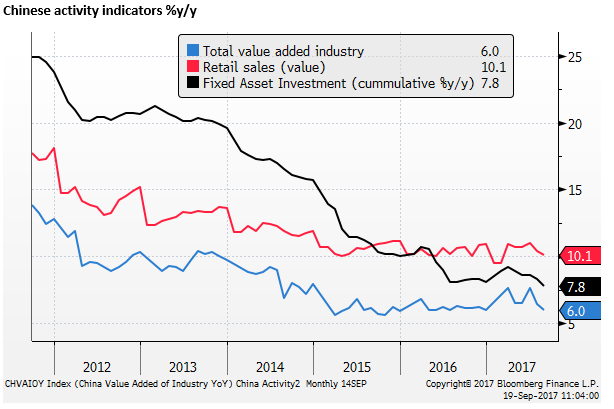

This view contrasts with the most recent data from China that has been weaker than expected in July and August. Fixed asset investment fell from 8.6% year-to-date-year-on-year in June to 7.8% ytd-yoy in August, which implies a pretty abrupt slowdown in the last two months. Industrial production slowed from 7.6%y/y in June to 6.0%y/y in August.

More consistent with the RBA assessment is that steel production has remained stronger, up 8.7%y/y in August. Compared to cement production that was down 3.7%y/y in August.

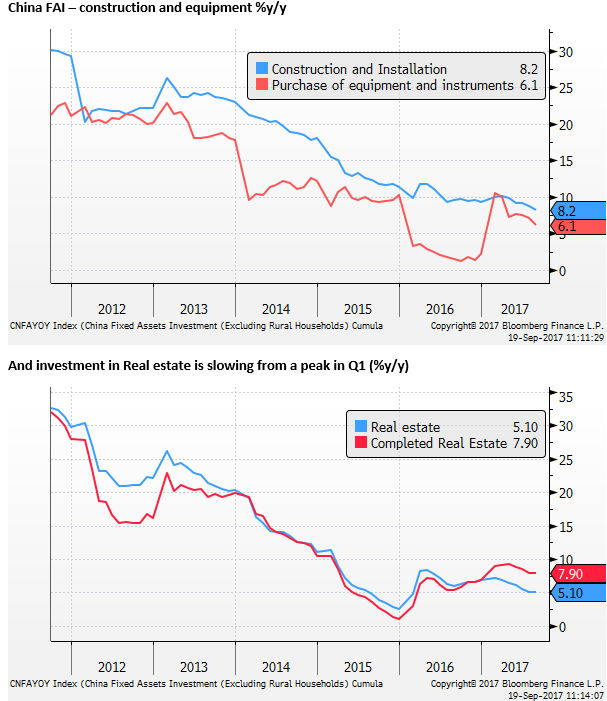

Looking under the hood of Chinese Fixed asset investment. Partial data suggest construction is slowing since April.

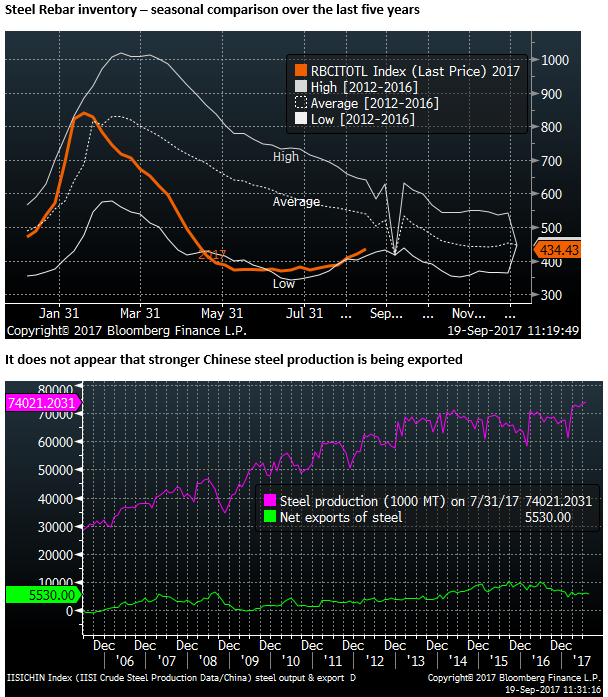

Against this fixed asset investment data, the recent strength in steel production looks out of place. Perhaps there has been some restocking from low levels of inventory after strong demand in 2016 and earlier this year.

The chart below suggests that steel inventories are low for this time of year, but are now starting to grow faster than the seasonal average.

Steel prices and, more so, iron ore prices have turned down recently; iron ore peaked around mid-August, steel in early-September. This may reflect slowing in Chinese demand for steel catching up with restocking.

Peak steel in China

These RBA minutes had a lot of longer-term references in the discussion. One of those was on Chinese steel demand. It suggested that Chinese growth in steel demand has reached a long-term peak, and projected a fall in iron ore prices.

It said, “Iron ore prices had been supported at higher levels because of sustained strong demand for steel in China. However, prices were expected to fall in the period ahead because of the ongoing expansion of global iron ore supply following an extended period of strong investment. Members also noted that Chinese steel production per capita was likely to be close to its peak and that growth in Chinese steel production would not add much to global demand for iron ore in the future.”

Further on the long-term theme, it said, “in the longer run, there was potential for India to have a noticeable effect on commodity markets as investment in residential construction and transport infrastructure increased.”

It is hard to pin the fall in iron ore prices in the last month on these long-term dynamics, but growth in China has slowed, iron ore prices are weaker, and the RBA is forecasting weaker commodity prices for the foreseeable future.

China a financial stability risk

China was a special topic researched and presented to the Board at this meeting. The RBA has highlighted China’s economic and financial restructuring as a risk to Australia’s growth outlook for some time. This concern was again in the minutes.

It said, “Members noted that the outcome of the 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in mid October would affect the pace and focus of further reforms, and influence how the authorities address the tension between achieving short-term growth aims and managing the build-up of risks to financial stability associated with rising debt levels.”

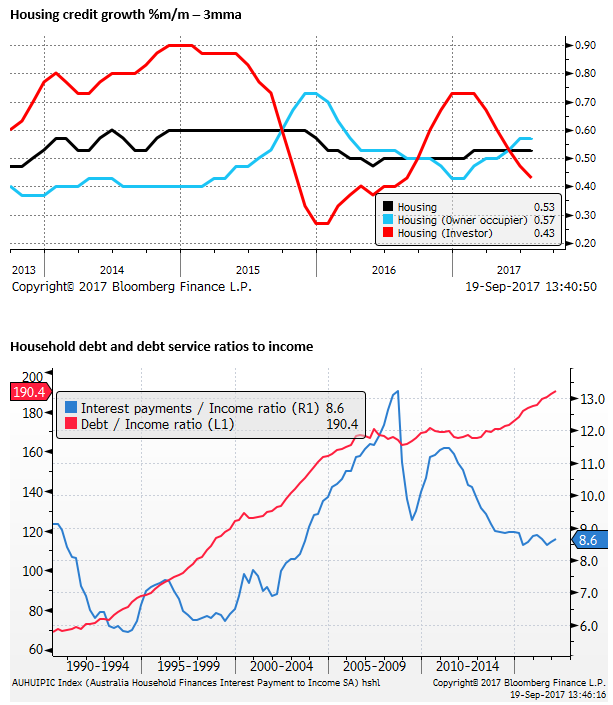

Homegrown debt problem

The RBA may be worried about China’s credit growth, but it is arguably not doing enough to deal with its homegrown household debt problem.

The RBA notes slowing credit growth to housing investors, but owner-occupier credit growth is taking up the slack. While banks have raised rates on investor loans, the RBA noted that “the average interest rate on new variable-rate loans was estimated to be around 30 basis points below that on outstanding loans.” And that “Average lending rates were estimated to have increased slightly over 2017”.

If the housing market is slowing down, despite the still stable overall credit growth, this may be a warning that the market is indeed heavy and vulnerable to a deeper correction.

A complex outlook

The broad analysis of the Australian economy is that its growth had been below trend over the last year, but employment growth, and thus total income growth, is strong. The investment outlook is improving gradually. A steady policy outlook should help reduce slack in the labour market and a gradual recovery in wage growth and inflation over the year or two ahead.

However, the risks to this rosy scenario are that slower growth in China and weaker commodity prices, and rising household debt and weaker house price growth in Australia, undermine the economic outlook.