Australian government tinkering with a ticking time-bomb

As Australia heads towards its May budget and a federal election later this year, debate over tax policy is heating up. The need to come up with fiscal plan is front and center in the wake of a collapse in commodity prices after it squandered the resources windfall. The debate is coalescing around reducing tax concessions on residential property investment. This is like defusing a ticking time-bomb that threatens to blow-up the Australian economy. It might be done smoothly, but the risk is high that it takes critical steam out the housing market just as it is approaching a peak. With one of the most leveraged households and most exposed banking systems to the domestic housing market in the world, the direction of government policy poses significant risks for the AUD and Australian financial markets.

Will an Australian government stand-up?

As Australia heads towards the mid-May annual Federal Government budget and an election around the end of Q3/beginning of Q4, politics and policy is featuring prominently in the Australian press and psyche.

The need to develop a feasible plan to return the budget to balance in the wake of a collapse in commodity prices and years of squandering the resources windfall has become the major discussion point in recent years.

The Liberal National Coalition (LNC) government that came to power three years ago on a promise to fix the budget failed miserably under the leadership of PM Tony Abbott and Treasurer Joe Hockey. Their bluff and bluster and three word slogans (“stop the boats”) so effective in opposition at dismantling support for the Labor led government of Kevin Rudd, then Julia Gillard, and Rudd again, failed to break through when in leadership.

After a gaff prone stint in power, Abbott was toppled from within his own party by Malcom Turnbull and Scott Morrison has taken the key post of Treasurer in only September last year. Turnbull himself had been leader of the opposition before Abbott when Rudd first rose to power in 2007, but was replaced by Abbott in a narrow vote, basically because many of the LNC members and the conservative loud-mouthed radio jocks they listen to wanted to oppose climate change policy.

The fickle Australian public have pinned considerable hope in the new leadership and confidence is at some of the best levels in recent years. The LNC looks like it will sail through the election later this year with the public still uneasy over the opposition Labor Party that was a shambles in government, and the opposition leader Bill Shorten is still tarred with that brush. That said, the current government led by Turnbull can ill-afford to blow it again after failing to make any meaningful budget reform in its first three-year term now drawing to a close.

In this state of nervousness, Turnbull snuffed out momentum that was building towards an increase in the Goods and Services Tax. Such policies are always hard to push through when it gets down to tick tacks over how to compensate the low income earners, whether goods should be exempt, where the funds should go, and what impact it might have on a fragile recovery. It appears he didn’t want to risk it. It remains to be seen if Australia has a politician capable of hard policy choices and a capacity to use political capital effectively.

Malcolm Turnbull’s task made harder by dumping of GST reform – AFR.com (by Allan Mitchell)

Scott Morrison: Tax reform is not Twenty20 cricket – AFR.com (by Jennifer Hewitt)

Playing with a ticking time-bomb

Debate now has shifted to increasing taxes (or rather reducing tax concessions) on retirement savings (called superannuation in Australia). And even more contentiously, reducing tax concessions on investment in residential property.

In the topsy-turvy nature of Australian political life, just as the ruling LNC appeared to have some ascendancy, the opposition Labor party has shown some Chutzpah and taken leadership in the tax debate, releasing a fairly detailed policy of limiting ‘negative gearing’ on residential property investment to newly built homes and halving the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) concession on investment property to 25%.

Debate over ‘negative gearing’ in Australia has raged for years, and is partly responsible for an irrational Australian love affair with property investment.

Since Labor leaked and announced this policy last weekend it has sparked a plume of press articles for and against. Those against primarily coming from people closely linked to the housing market.

Bill Shorten would take an axe to housing investment – AFR.com (by Robert Harley)

Negative gearing plan worth $7bn a year in a decade: Labor – AFR.com

Whether Labor has genuinely led the debate, or was smart enough to realize which way the debate was heading next, it appears there is now enough cover and discussion for the LNC leadership to release its own version of changes to negative gearing and CGT.

A proposal they appear to favor, probably to be different and not look like copy-cats, is to limit the number of properties that may be negatively geared, or limiting the amount of the tax deduction. Some form of change to negative gearing and GCT appears almost inevitable (according to housing market editor at the AFR Robert Harley).

This is more than an esoteric debate over how to raise government revenue; tinkering with tax policy on housing in Australia is like defusing an economic bomb. It might be done smoothly, but if you mess it up, you threaten to trigger an economic and financial collapse.

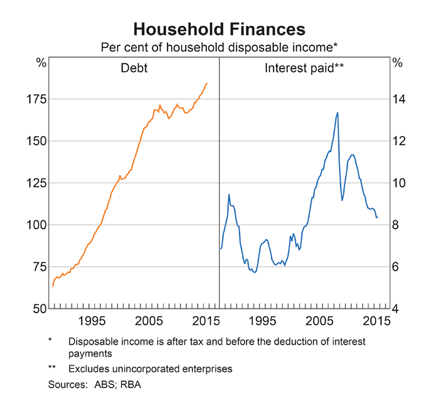

Australians have collectively run-up mortgage debt to be one of the most leveraged nations in the world in terms of debt-to-income ratio; both to buy their own home, and some also second, third, fourth and so-on additional properties; often with the aim of making capital gain.

The basic idea of negative gearing is that investors can deduct the interest costs on the mortgage for their investment property against not only the income from that property, but also his/her overall income. Negative gearing, therefore, encourages investors to highly gear, borrow as much as possible, against their investment property.

Furthermore, once people get the bug for property investment they tend to routinely use as much borrowing capacity as they can muster to keep going, using equity from capital gains in one property to increase their loan and provide the capital for a down-payment on the next. Some prominent commentators have described negative gearing as akin to a ‘Ponzi scheme’.

‘Ponzi scheme’ or vital investment tool: Business divided on negative gearing – AFR.com

Banks heavily exposed to housing

Banks have been complicit in this process, competing aggressively in the mortgage market, keeping mortgages relatively freely available compared to banks in many countries. While regulators in Australia helped prevent banks from making the mistakes of sub-prime and low-doc lending and aggressive securitization practices that brought the US and global financial system unstuck in 2007/08, Australian banks are more exposed to their domestic mortgage market than most other banking sectors in the world, in a country whose households are one of the most leveraged in the world.

Astute investors are often closely monitoring the Australian housing market for any cracks, since if and when this happens the fallout to households and banks and the overall economy is potentially very large, perhaps even catastrophic.

To date, the fabled Australian housing market crash has not occurred and the Australian financial system and economy sailed through the Global Financial Crisis and Eurozone debt crisis unscathed. So much so that Australian banks are now some of the strongest in terms of balance sheet, capital and profitability in the world.

It may not be a bubble, but it’s something

There are indeed a number of idiosyncratic features of the Australian property market that account for its resilience that are not well understood by foreign investors making comparisons with the US and UK property and banking system collapses in 2007/08. Australians are primarily large city dwellers and much more of its housing stock is concentrated in its large east coast cities. Large cities where land is scarce tend to have stronger more stable property prices. Immigration has supported demand, and in recent years, Chinese and other Asian buyers have sort property in Australia.

Arguably, Australian state governments have under invested in infrastructure and maintained archaic zoning standards that have discouraged faster growth in the housing stock. One might even argue that the State government system is biased towards encouraging higher property prices and property market turnover, allowing them to reap high tax revenue from stamp-duty on sales.

You might not describe it as a housing bubble, but it is widely argued that Australia would be in a better place and better served if households had not been so driven towards housing investment and more incentivized to diversify into a range of investments that might have funded business opportunities where capital has been more tightly rationed. Banks have in the past been far less interested in lending for small business.

Housing values remain central to the stability of the Australian economy, not only in terms of financial stability but also to the confidence of households that are highly levered and more invested in housing that most other nations. Prices could fall after several years of rising to new records without unravelling the financial system, but such an event would probably still contribute to weaker confidence and economic growth.

Some housing headwinds in the last year

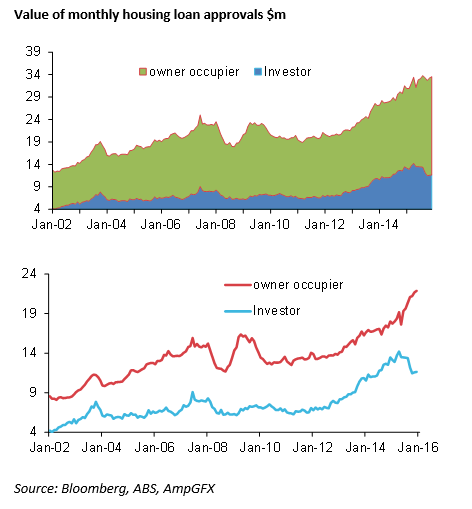

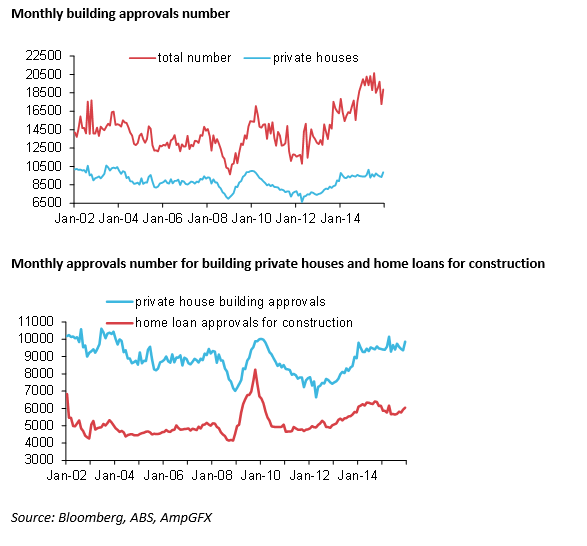

Residential building has been one of the strong parts of the Australian economy over the last two years, helping the economy transition through the down-turn in mining investment. The RBA has been in a bit of a confused state, on the one hand cutting rates to record lows and encouraging some rise in house prices to encourage investment and building activity. But from around Q3-2014 it started to worry about rapid investor loan growth and rapid price appreciation in the major cities increasing financial stability risks.

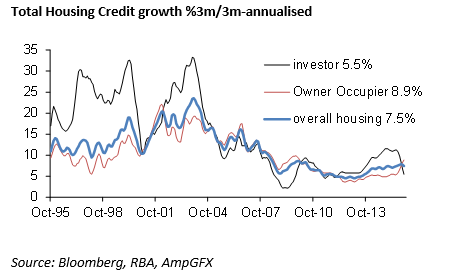

It led the discussion to impose some macro-prudential restraint on investor lending that began to gently restrain this segment of the market from around mid-2015 (albeit after what appeared to be a rush to expand investor loans in the first half of 2015). Cynically one might say banks and the housing industry lived up to their penchant for mortgage spruiking by helping the market get in ahead of speed limits on investor lending. However, since mid-2015, banks have tighten availability and raised rates somewhat on investor loans.

The ire many Australians felt watching Asian-faced investors on the phone to supposedly rich Chinese buyers snapping up properties at auction led the government to also crack-down on foreign investment rules and introduce some higher transaction fees on foreign investment.

Thirdly, in response to recommendations from a Financial Systems Inquiry tabled at end 2014, in mid-2015 the bank regulator APRA required banks to raise their average capital risk-weight applied to mortgages to at least 25% (up from an average of around only 16% of loan assets), and raise more capital in general. In response, in October last year, banks raised their mortgage rates on average by around 20bp.

As a consequence of these measures, and decreasing affordability after several years of rapid price growth and an increase in the supply of apartments, price growth in the Australian housing market has cooled and residential building approvals have started to stall at a relatively high levels.

Still some life in the party

However, it is far from clear that the housing market in Australia is spent. The most recent data on approvals, finance and prices have firmed a bit.

Even though the growth in investor credit has slowed from a too-rapid 11% annual pace around mid-2015 to around 5% annualized in recent months, a large part of this is associated with a reclassification of existing loans from investor to own-occupier loans, and overall mortgage credit growth has been stable at a cyclical peak of 7.5%y/y. With a stock of debt well above household income (in a ratio of around 180% and climbing), 7.5% annual growth in mortgages is still arguably too high.

Tax change may take critical steam out of the housing engine

The high volume of press around negative gearing and CGT changes coming at a juncture when the housing market may be around a medium term peak but is yet to clearly turn.

Just the increased discussion over these tax changes that influence a key segment of the market – investors – could be enough to take critical steam out of the housing engine.

There are many unknown variables. Will the changes apply to only existing housing stock (as Labor propose)? Will the changes be applied to only new purchases or investment properties already held? Will the government prefer a deeper cut in the CGT concession over cuts to negative gearing concessions?

If you were an investor worried about losing CGT concessions you might decide to sell earlier rather than later. If you were an investor worrying about negative gearing being removed on purchases made after a certain date, you might buy sooner.

Overall, however, the bigger concern for those with several properties may be lost CGT concessions and the risk of a down-turn in the market.

Talk around these tax changes is likely to both increase uncertainty and skew it more to the downside for investors. Therefore we should be wary of a down-turn in the Australian housing market occurring sooner and more clearly this year.