How Dovish will the Fed be?

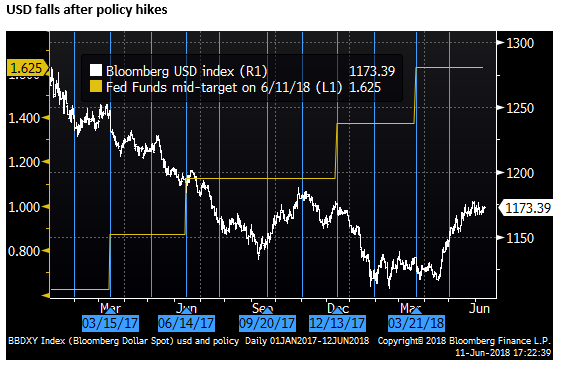

Every Fed rate hike over the last year and more has resulted in a weaker USD, suggesting the Fed has a habit of delivering ‘dovish’ hikes. There is every reason to expect the same this week. The May policy minutes sent a number of dovish signals; concern over a flattening yield curve, ambivalence on the labor market and wages, concern over trade policy, a desire for a period of above-target inflation, thoughts that policy is getting near neutral, and the Fed funds creeping up to the IOER. There is evidence that Fed policy tightening is causing financial stress in some emerging markets. A weaker USD may be seen as a good thing for stabilising global markets. The parallels between the weaker EM currencies and the USD (unsustainable fiscal policies, external deficits and populist strong man politicians) suggest the Fed and Congress should be preparing for their own reckoning.

Dovish Hikes

More often than not during the Fed policy hiking cycle in the last two years, the USD has fallen after FOMC policy meetings. In fact, it has tended to fall more often on the meetings at which hikes have been delivered.

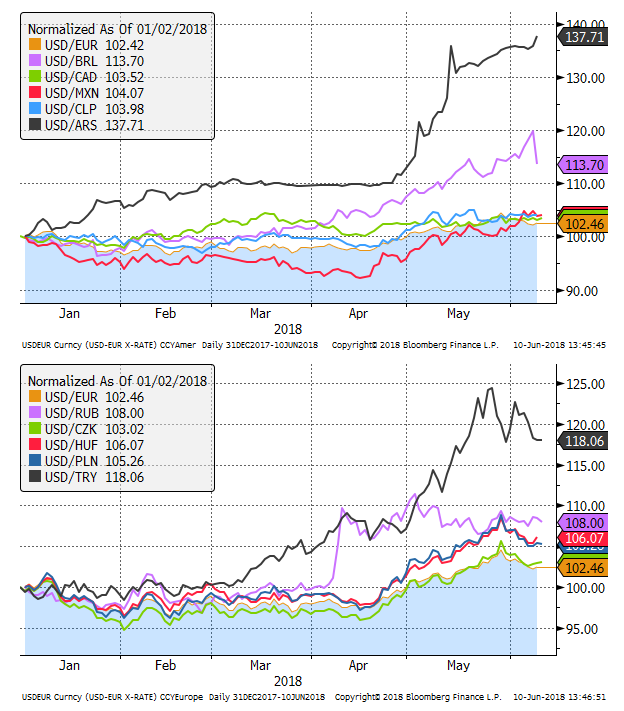

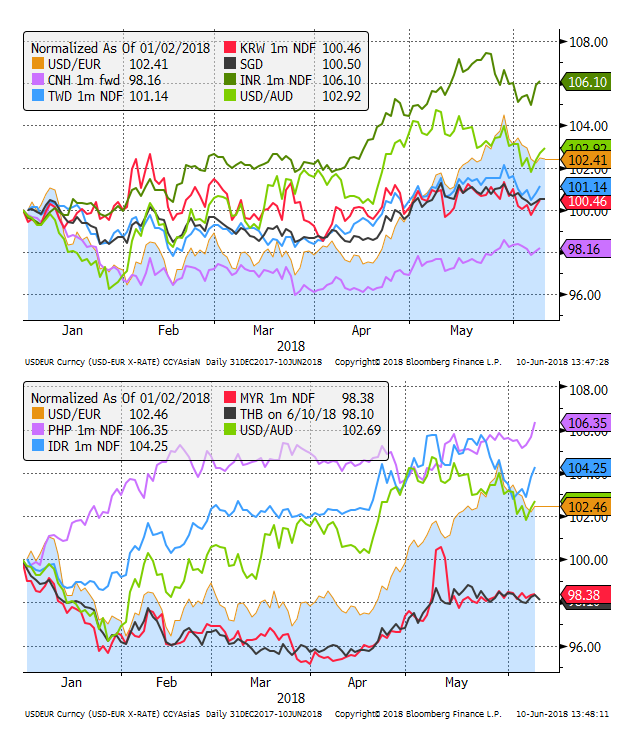

Global Financial market uncertainty

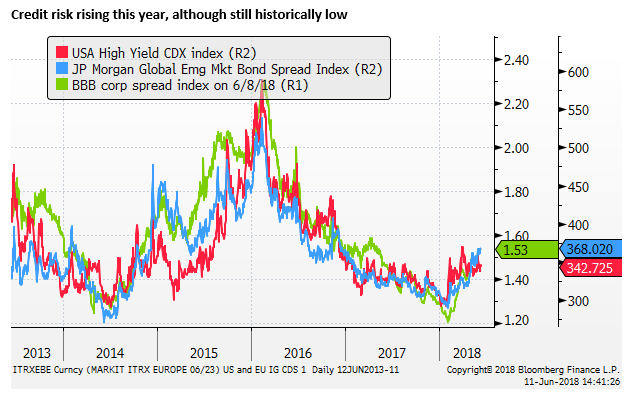

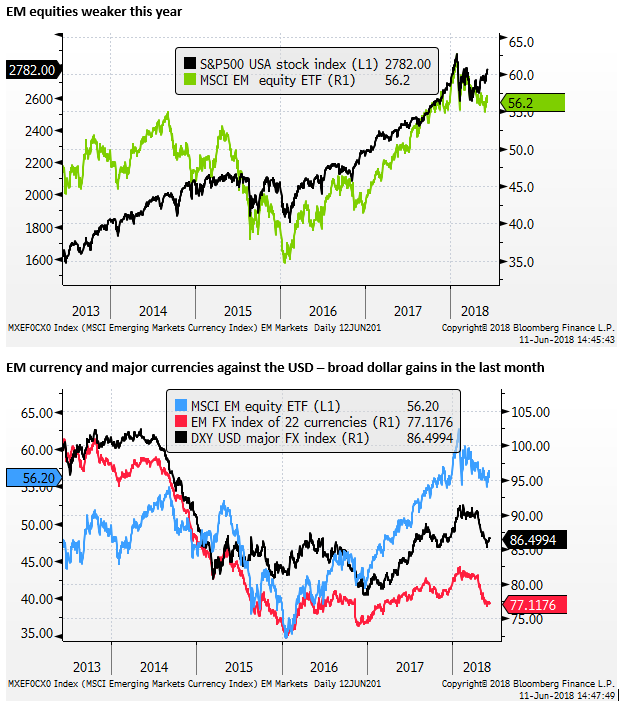

Global financial market uncertainty has increased in the last month and rose to a peak for some emerging markets last week. Those hit hardest are among the most vulnerable to rising US rates and tightening credit conditions; with high fiscal and/or current account deficits, and upcoming government elections with populists leading in the polls.

Populist strong men and weak currencies

A key factor in undermining financial conditions in vulnerable EM markets was the recent upheaval in Italian politics. Like Brazil, Mexico and Turkey, where elections are coming soon, Italian asset markets were befallen by populist politicians embarking on unsustainable fiscal spending.

Luckily for Italy, at least for the time being, it has the direct support from ECB asset purchases, which have probably prevented a worse outcome.

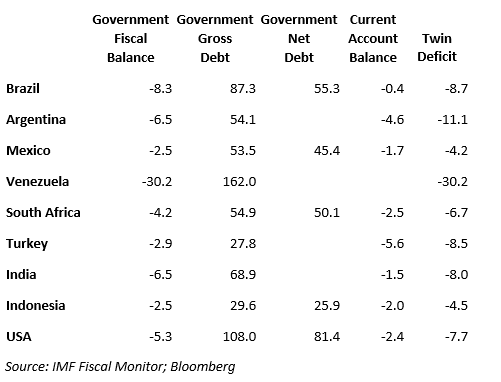

The parallels in the USA should not be ignored. While US financial markets are strong, it too has a populist government that has succeeded in blowing out its fiscal deficit with no plan and little hope of reigning it in any time soon.

While the Fed is tightening policy at the moment, it is arguably complicit to the government excess. It has made little comment on the sustainability of US government finances. US President Trump arguably dumped the previous Fed Chair (Yellen), to replace her with one (Powell) that, to get his job, had to hold his tongue when commenting on US fiscal excess.

As the table above shows, the US fiscal and external position is hardly any better than some of the more vulnerable emerging markets. It is fair to say that the USA is relying on its reserve currency status and the dollarisation of global financial markets to provide it stability.

US policy tightening screws on EM

One of the more interesting observations from high profile officials in the last week was the op-ed by the Indian central bank governor Urjit Patel in the UK Financial Times.

Emerging markets face a dollar double whammy; Urjit Patel – FT.com

He said, “Dollar funding of emerging market economies has been in turmoil for months now.”…. “The upheaval stems from the coincidence of two significant events: the Fed’s long-awaited moves to trim its balance sheet and a substantial increase in issuing US Treasuries to pay for tax cuts. Given the rapid rise in the size of the US deficit, the Fed must respond by slowing plans to shrink its balance sheet. If it does not, Treasuries will absorb such a large share of dollar liquidity that a crisis in the rest of the dollar bond markets is inevitable.”

“That shrinkage will peak at $50bn a month by October and total $1tn by December 2019. Meanwhile, the US fiscal deficit is projected to be $804bn in 2018 and $981bn in 2019, implying net issuance by the US government of $1.169tn and $1.171tn, respectively, in the two years.”

Indeed, as it stands, the USA is soaking up a bigger share of global savings, making it harder for EM markets. The central role the dollar plays in global finance and the pseudo-safety that US government bonds provide, allows the USA to crowd out and take first dibs on capital that might otherwise be available for EM countries.

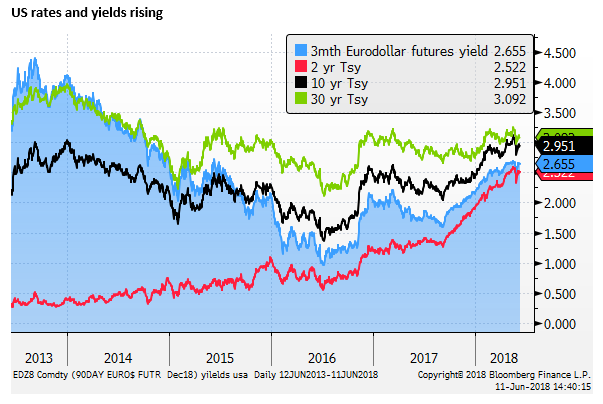

The way the USA government crowds out EM borrowers is by offering somewhat higher yields, and indeed US yields have moved up moderately. Not so much yet to significantly tighten US financial conditions, but sufficient, it seems, to place pressure on weaker less attractive asset markets abroad.

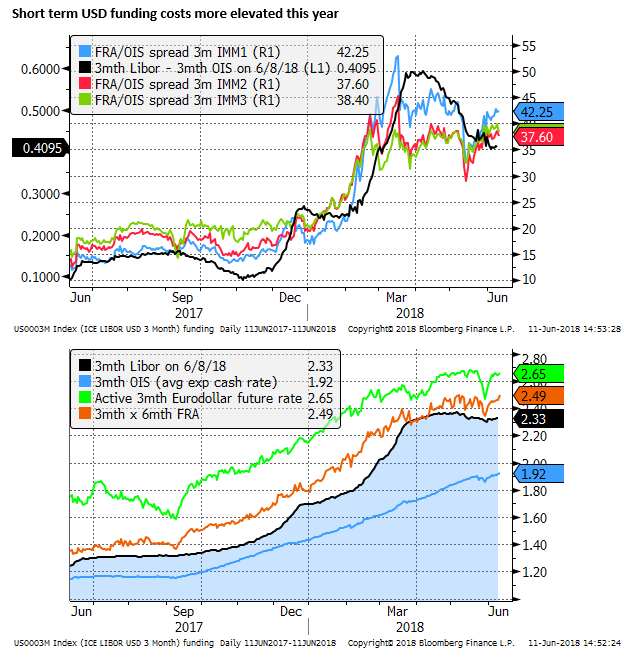

The tightening in financial conditions is also apparent at the shorter end of the yield curve, where a higher issuance of US T-bills has contributed to wider spreads in dollar interbank money market funds.

Another contributing factor is thought to be the US tax policy changes that have encouraged US company repatriation of offshore retained earnings and more onshore borrowing by foreign companies’ subsidiaries in the USA.

This has added to dollar funding costs. Most officials and commentators do not see it has a sign of broader credit tightening. Corporate credit spreads in the US further out the curve have not widened much. Cross-currency basis swaps have not widened. Nevertheless, it is a part of some tightening in credit conditions that may be affecting weaker credits and EM markets.

The global economy may still appear in reasonable shape, but certainly, we should expect some moderation in global growth confidence as rates and yields rise in several emerging markets, and availability of capital diminishes.

The chart below shows the spread between 3mth USD LIBOR and Fed-fund cash rate expectations (OIS) widened sharply from around 13bp to around 50bp over the first three months of this year. It has since eased to around 35bp. However, forward expectations of this spread have started to widen again to around 40bp over the last month.

Is Patel asking the Fed to monetise excessive fiscal spending?

What is also fascinating about RBI governor Patel’s comments is that he is calling on the Fed to slow the pace it winds down its balance sheet. Not so long ago, central bank buying government debt was considered an “extraordinary” measure, and a threat to currency stability. It was thought to be very much like “monetising” government debt, the type of actions that threatened to debase a currency and lead to hyperinflation. The only difference was that officials convinced us it was intended to be only temporary and expected to be reversed after the emergency (deflationary spiral) was over.

However, now, not so long after the music has been turned off, Patel has started the call to keep it going. He has, at this stage, only called for a slowing in the pace of Fed asset wind-down. But the comment has bigger implications. The need for the Fed to re-think its asset wind-down, according to Patel, arises because the US government has increased its borrowing. It is not too far from saying the only way to prevent a global financial crisis is if the Fed offers to monetise its government’s debt.

Fed needs to warn Congress

More sensible, would be for the Fed to start to warn Congress that it is out of control. Its borrowing is not sustainable, and the Fed does not want to have to provide a backstop for its rising supply of bonds if/when the next economic downturn comes.

However, Congress appoints the Fed Board of Governors. Trump has already effectively kicked out the last Chair, in my view, because she might have been less complicit with his fiscal and banking deregulation plans. Powell is still considered a safe pair of hands, but he has gone out of his way to say little about fiscal policy and has supported less banking regulation.

Fed independence may be tested down the road

There has been little pressure on Powell’s policy direction so far; a policy of gradual rate rises and a steady unwinding of the Fed’s bond asset portfolio. However, both these policies were set in place before he took the helm, and there has been no reason, as yet, to alter course.

The only pressure has come from some upheaval in a few weaker EM countries. There are some visible risks abroad, but not yet enough to spill over to the USA, or force a big shift in the mindset of FOMC members.

Having added asset-purchases to the Fed’s policy tool-kit, it appears that the Fed is fully prepared to use them again. They are no longer considered extraordinary or emergency measures. It is not even clear that the Fed would cut rates to near zero again before re-starting asset purchases.

If financial and economic conditions in the USA begin to weaken again. You can only imagine the pressure Trump would place on Powell and the Fed to ease policy.

Luckily for Powell, Trump can’t just fire him, but Trump is hardly the type to respect the sanctity of central bank independence. Consider the impact on the TRL recently when Turkish President Erdogan suggested he would take more responsibility for monetary policy if re-elected.

Trump is very much in the same mould of a strongman populist leader that is weakening confidence in some EM currencies. And the USA fiscal, debt and current account position is in the same weak state as these EM countries.

Pressure on the Fed is building

As mentioned, the Fed hasn’t been under pressure yet. But pressure is starting to build. As the FOMC meets this week, the labour market is tightening to a crucial degree, inflation has crept back to approach its target, wage growth is still modest, but creeping up, interest rates are getting closer to perceptions of neutral, and government borrowing is higher and not sustainable over the long term.

There is some stress in emerging markets. Trump has started a trade war with his allies and China. He has pulled out of an Iran deal and a climate change deal and has arguably scuttled years of goodwill and US power internationally.

The Fed might not feel the heat yet, but the fire is burning outside its door from domestic and international sources.

Fear of over-tightening

The Fed has been raising rates, and this has supported the USD. But the USD has struggled because the market suspects that at the first sign the economy is losing speed, the Fed will change course. What is more, if that happens at the same time that inflation is rising, and demand for US government bonds weakens on fears its debt trajectory is off the rails, then the Fed will be in the same awkward position some emerging markets find themselves; deciding whether to hike rates to save their currency and halt inflation, or allow a deeper domestic economic collapse.

As we head into the Fed meeting this week, deep down, FOMC members may be feeling the pressure building. This is likely to make them fear over-tightening policy. They are likely to take more risks with inflation in the near term to ensure the music keeps playing.

The inner voices of FOMC members may say that the USA and the global financial system is not well prepared for sustained strength in the USD or substantially higher US yields. As such, this week may be another ‘dovish’ hike by the Fed.

It will be far from a convincing act that they can douse the flames burning just outside their doors. What they need to do is start warning Congress that it needs to get its fiscal house in order.

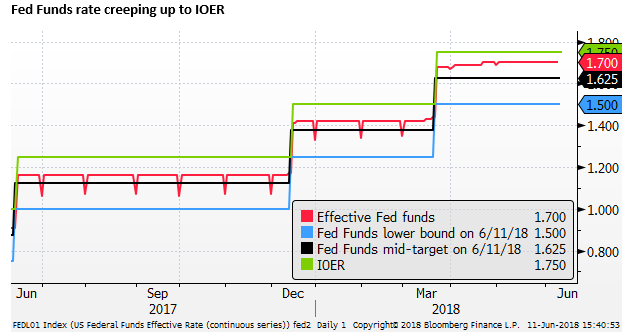

A lesser hike for the IOER

The FOMC is likely to raise the Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER) a bit less than the Fed-Funds target rate. And this could be interpreted as a dovish tilt.

The IOER is the rate that the Federal Reserve pays banks for the funds left on deposit at the central bank. It has been set at the top of the Fed Funds target range (currently at 1.75%).

In the 1-2 May FOMC minutes, the Fed staff noted that the effective Fed funds rate had been creeping higher (above the mid-point of the Fed’s target range – 1.625%); currently, it is around 1.70%. This reflects the increased supply of T-bill issuance by the government this year, and the related broader rise in dollar funding costs described above.

The Fed staff suggested in the minutes raising the IOER 5 bp less (+20bp) than the Fed funds rate target band (+25bp) next time the FOMC hiked. The aim would be to place a little downward pressure on the Fed funds rate to sneak it back nearer to mid-target.

This would no doubt be presented as a technical adjustment; nothing to do with monetary policy. But the bottom line is that it will be intended to lessen the rise in rates that filter through the money markets, to counter some of the unintended rise in rates this year.

Dropping forward guidance

A real kicker in the more dovish than expected department would be if the Fed acknowledges that policy is getting close to neutral. They could drop their ‘forward-guidance’ on rates by removing or adjusting the sentence in their policy statement: “the federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run.”

The May FOMC minutes said that a ”few participants noted that if increases in the target range for the federal funds rate continued, the federal funds rate could be at or above their estimates of its longer-run normal level before too long.”

In addition, “a few observed that the neutral level of the federal funds rate might currently be lower than their estimates of its longer-run level.”

The “central tendency” of FOMC estimates for the long-run neutral rate is between 2.8 and 3.0%. Assuming the FOMC proceed with a hike at its next meeting, it will have Fed Funds between 1.75 to 2.0% (around 1.9%).

At what point does the Fed conclude that the Fed funds rate is close enough to neutral that it need not keep saying it is likely to remain below neutral for some time? It will be within one percent after this week, and some think the current neutral rate is less than the long run neutral rate.

There is a high probability that the Fed drops the “some time”part of its forward guidance in its statement this week. This will be seen as leaving them more options to pause on further rate hikes ahead – a dovish tilt.

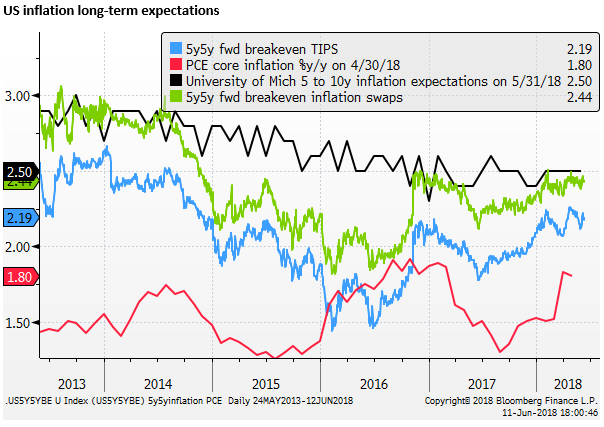

The FOMC is happy to see inflation run above target

On inflation, there is a school of thought in the FOMC that running inflation above 2% for a while would be a good thing to help lift longer-term inflation expectations.

The May FOMC minutes said, “In light of subdued inflation over recent years, a few participants observed that adjustments in the stance of policy should take account of the possibility that longer-term inflation expectations have drifted a bit below levels consistent with the Committee’s 2 percent inflation objective.”

In addition, “It was also noted that a temporary period of inflation modestly above 2 percent would be consistent with the Committee’s symmetric inflation objective and could be helpful in anchoring longer-run inflation expectations at a level consistent with that objective.”

This viewpoint accounts for the Fed’s inclusion of an extra (second) reference to the inflation target of 2% being “symmetric” in the May policy statement.

While most Fed members have avoided publicly saying they want to run inflation above target for a time, it certainly appears they would not think it a bad thing.

Mixed feelings on the labor market

The Fed has expressed mixed feelings on the tightening in the labor market. It appears that they are reluctant to preempt any pick up in wage growth, and are willing to wait until wage growth rises more clearly before concluding that the labor market is tightening too far.

Minneapolis Fed President Kashari is a lead voice of “several participants” that see scope for more people to join the workforce, as has been seen in some other countries, and are less convinced wage growth is about to take-off. He made this point even after the recent fall in the unemployment rate to 3.8%.

The May minutes said, “some participants thought that a strengthening labor market could bring a further increase in labor supply, allowing the unemployment rate to decline further with less upward pressure on wages and prices.”

Trade policy risks to growth

The May minutes said, “in a number of districts contacts expressed concern about the possible adverse effects of tariffs and trade restrictions, including the potential for postponing or pulling back on capital spending.”

In light of the recent Trump administration policy maneuvers and rhetoric, those concerns are likely to have increased.

The survey and hard data do not suggest that investment plans have been derailed. There is every reason to see the government’s tax policy as significantly boosting corporate investment. And indicators have been robust coming into this meeting. As such, business investment is likely to be still be considered a strength and a reason to hike further.

Nevertheless, FOMC member reservations about the impact of trade are likely to be seen adding uncertainty and downside risks to their outlook. Something Powell may feel he is compelled to acknowledge if, as is very likely, he is quizzed on trade policy at the press conference.

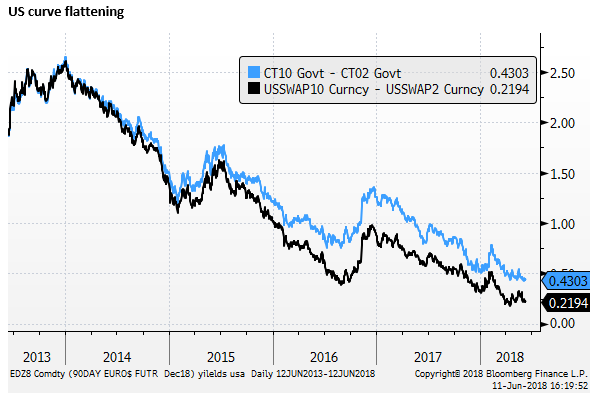

Curve shape worries

Curve flattening has been seen by some Fed members as a sign that financial conditions are tightening and the Fed may be closer to reaching neutral rates than generally thought.

The May minutes said, “several participants thought that it would be important to continue to monitor the slope of the yield curve, emphasizing the historical regularity that an inverted yield curve has indicated an increased risk of recession.”

The Fed is fully expected to hike rates this week. Q2 GDP is expected to accelerate sharply from the soft Q1 and lift annual GDP growth to around 3%. The Atlanta Fed GDPNowcast is predicting a 4.6%q/q SAAR rise in Q2, which would be the biggest increase since 2014.

But there are a number of reasons for the Fed to play it cool on the rates outlook. It actually want inflation to run above 2% for a while, it is still not convinced wage growth is about to pick up, It is seeing more risks from stress in global markets and trade policy uncertainty. Policy may be approaching neutrality. The Fed may be wondering if the stress in global markets has got something to do with its policy tightening and it is time to proceed with more caution.

Elections are coming in Turkey, Brazil and Mexico

Populists from the left and the right are reported to be gaining support in the election race for President of Brazil set for Oct-2018. Centrist candidates associated with the reformist administration of Michel Temer are reported to be well behind in the polls. The fear is that a new President will risk derailing fiscal consolidation.

The IMF Fiscal monitor forecast the Brazilain fiscal deficit at 8.5% of GDP in 2018, and net government debt of 55.3% of GDP. Its current account appears in good shape at -0.4% of GDP according to Bloomberg data.

Brazilian general election, 2018 – wikipedia.org

The Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan called an early election (on 18 April) to be held on 24 June. While his AK Party may lose a parliamentary majority, Erdagon is expected to be returned as President. And in doing so gain more powers since the constitutional referendum in 2017 set Turkey on a path to switch from a parliamentary system of government to an executive presidency.

The IMF Fiscal monitor forecast the Turkish fiscal deficit at 2.9% of GDP in 2018, and gross government debt of 27.8% of GDP. Turkey’s current account appears more troublesome at -5.6% of GDP according to Bloomberg data.

Turkish general election, 2018 – wikipedia.org

Mexico elections are set for 1 July. The clear front-runner is Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO). As Leader of a Leftist party, he is campaigning to reduce poverty and end corruption. He say’s he’ll take on President Trump, but his nationalist ideas are similar in many ways to Trump. The market again fears his populist policies might blowout fiscal spending.

The IMF Fiscal monitor forecast the Mexican fiscal deficit at 2.5% of GDP in 2018, and net government debt of 45.4% of GDP. Mexico’s current account appears in reasonable shape at -1.7% of GDP according to Bloomberg data.

Mexican general election, 2018 – wikipedia.org

Further undermining the MXN is the threats from Trump to pull out of NAFTA. The blow-up between Trump and Canadian PM Trudeau over the weekend, after the G7 meeting, poses further risks that a NAFTA deal will remain elusive; undermining economic confidence in Mexico.

India, Indonesia and Turkey hiked rates

Indonesia has raised policy rates twice in May 4.25% to 4.75% to stabilise the IDR.

Argentina secured a $50bn credit line from the IMF after a series of rate hikes and intervention in recent months failed to arrest a precipitous fall in the ARS

India raised its policy rates for the first time since 2013 from 6.0% to 6.25%

Turkey raised rates for a second time in less than two weeks on Thursday last week to 17.75%, from 8.0%. The decisive rate moves halting falls in recent weeks.

On Friday, the BRL rebounded on central bank intervention, after reaching a new low on Thursday since 2016.