More Trouble for AUD and NZD

After the recent rise in global yields, AUD and NZD now appear to be in the process of unwinding strength generated by a ‘search-for-yield’ during the first three-quarters of the year. Both currencies have scope to fall to re-connect with narrower yield differentials following rate cuts earlier this year and higher rates in the USA. The bigger source of downside risk for these currencies is the pressure higher global yields may place on domestic economic growth as highly leveraged households face higher mortgage payments. Australian and New Zealand household leverage has risen to new records, exceeding pre-GFC levels, whereas USA household leverage has declined significantly. Australian and New Zealand banks still rely significantly on foreign funding sources. Higher global yields and regulatory pressure to switch to longer term sources of finance are already raising funding costs for Australian banks. Extended housing markets, an apartment glut in Australian cities, and macroprudential policy tightening in New Zealand also generate risks in the crucial housing market. A probable sovereign ratings downgrade in Australia is expected to feed through to somewhat higher mortgage rates in the year ahead. The recent sharp rise in Chinese rates and yields across maturity and credit segments points to financial stress in China generating risks for the Australian and New Zealand economies. Furthermore, both the RBA and RBNZ would prefer a policy mix of a lower exchange rate and higher interest rates, suggesting they will not be an impediment to further significant falls in these currencies.

Reconnecting to lower interest rates

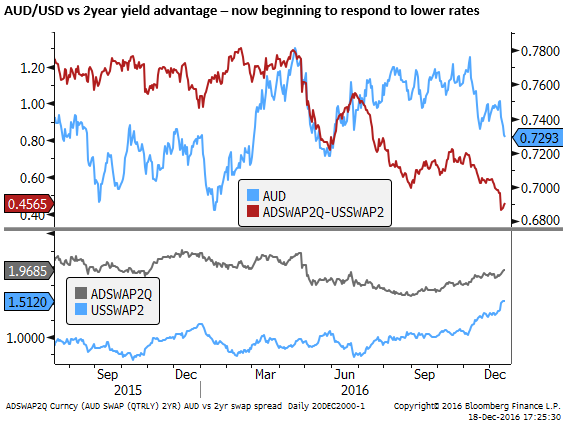

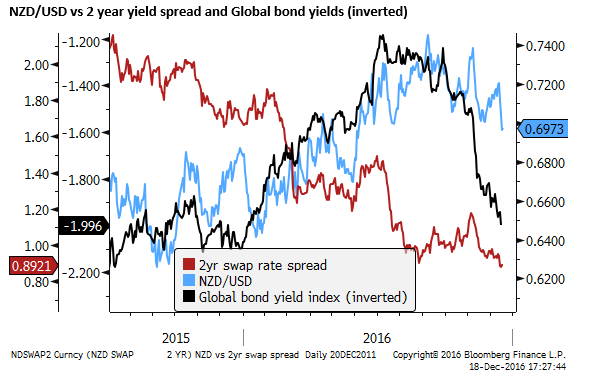

We have discussed in recent reports that higher global yields were likely to undermine the NZD and the AUD. Both currencies, along with other higher yielders, had benefited in the first three-quarter of the year from a ‘search for yield’ in a diminishing global yield environment. In recent trading, yields may have risen enough to start to have a more significant negative impact on these currencies.

Headwinds stiffen for Australia 2-Dec – ampGFXcapital.com

Two currency themes to unwind 16-Nov – ampGFXcapital.com

Both countries cut their policy interest rate further this year, in part to hold back strength in their currencies and boost inflation. This extended their rates to record lows, narrowing their interest rate advantage over USD to relatively thin margins. In a falling global yield environment, with yields at record low levels, the currency market paid little attention to the narrowing interest rate differentials. After the recent surge in global yields, we may now be in the process of reconnecting AUD and NZD to the earlier fall in their interest rates.

The chart below compares the NZD to the JPMorgan aggregate global bond yield index and the NZD 2-year yield spread over the USD. The global yield index has risen noticeable since end-Sep, accelerating higher after the Trump election victory in the last month or so. The NZD has fallen from its peak in September, although it is still at relatively high levels.

Since Friday, the NZD/USD is also flirting with forming a head-and-shoulders topping pattern, and breaking below its recent declining channel.

A bigger threat is the fallout for household finances

The impact of higher bond yields on global investor attitudes towards higher yielding currencies aside, the other avenue through which AUD and NZD are vulnerable to higher global yields is via high household debt and an ongoing reliance by Australian and New Zealand banks on offshore funding sources.

The latter source of downside risk for these currencies may be the big kicker, switching these currencies into a more significantly bearish gear. If yields start to rise more significantly, it could spill over into weaker consumption spending in Australia and New Zealand as households find their finances undermined by higher mortgage payments.

Policy makers would welcome a lower exchange rate

It is conceivable that both countries find themselves in the unusual circumstance of rising interest rates and falling currencies. In many respects, policymakers in both countries would be happy with such a development. Rising household debt has been a bugbear for some time, fueling excessive housing speculation and generating financial stability risks. Higher rates would be seen as leaning against further credit growth.

Rising exchange rates in both countries have been undermining efforts to boost traded goods and services sectors and business investment. Both countries would prefer a policy mix of a weaker exchange rate and higher interest rates.

The RBNZ has repeated in its policy statement since August that “A decline in the exchange rate is needed”. And the RBA has said since May that an “appreciating exchange rate could complicate” economic adjustment.

As such, neither central bank is in a mind to stand in the way of weaker exchange rates. In fact, as described above, raising interest rates to support the currency may be counter-productive if it serves to undermine consumption and household confidence.

RBNZ measures to limit household and bank leverage

The RBNZ reported in its 30 November Financial Stability Report that the ratio of household debt to disposable income rose to 165% in June, above its pre-global financial crisis (GFC) peak.

It said, “Low interest rates have reduced the current debt servicing burden, but high debt levels leave some households exposed to future income and interest rate shocks. International evidence from past housing market downturns shows that highly indebted households are more likely to (i) default on debt and (ii) reduce consumption by more during downturns, leading to spillovers to other sectors and amplified bank losses during a housing market downturn.”

The RBNZ have been battling against rising household debt and related financial stability risks for several years now. It implemented controls on Loan-to-Valuation ratios (LVR) since 2013, reducing leverage in the housing market to help contain house price gains and bank exposure.

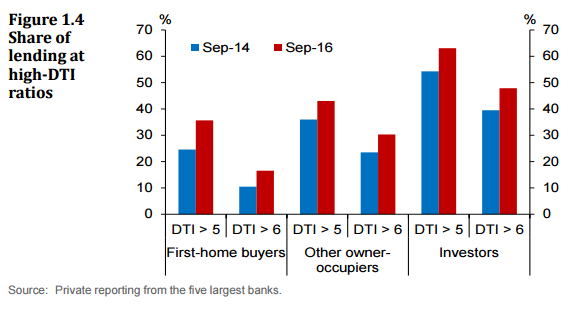

More recently it has shifted gear to express concern more directly in the rise in Debt-to-Income ratios (DTI). It said, “Lending at relatively high LVR and DTI ratios is particularly concerning because (i) borrowers with higher DTI ratios are more susceptible to income or interest rate shocks and (ii) high-LVR borrowers are less able to sell their house to pay off their debt, should they suffer an income or interest rate shock during a period of falling house prices.”

“The availability of loans to borrowers with DTI ratios greater than 5 has increased substantially since the GFC, as high house price inflation has reduced housing affordability and low interest rates have increased the debt capacity of borrowers. The share of lending at DTI ratios over 5 has increased for all buyer types since 2014 (figure 1.4). For example, the mean DTI ratio for a first-home buyer in the top half of the distribution has increased from 5.2 to 5.7, and has increased from 7.5 to 8 for investors.”

At the time of the FSR release, the RBNZ said that it had “asked the Minister of Finance to agree to add a Debt to Income (DTI) tool to the Memorandum of Understanding on macro-prudential policy. While the Bank is not proposing use of such a tool at this time, financial stability risks can build up quickly and restrictions on high-DTI lending could be warranted if housing market imbalances were to deteriorate further.”

The New Zealand economy appears relatively strong, supported by rapid immigration growth and construction activity and wealth effects from high house prices. However, the RBNZ has highlighted how the good vibe economy may be undermined by rising interest rates hitting highly levered households. If this were to then spillover to weaker house prices, economic confidence and financial stability in the banking system could deteriorate further.

The good times were rolling in a falling interest rate and low yield environment; they may deteriorate quickly and significantly in a rising interest rate environment.

The housing market in New Zealand has been losing steam since around Q3, not long before the RBNZ stepped up its macroprudential tightening measures by expanding the application of and lowering LVR thresholds for mortgage lending. This may have allowed the RBNZ some additional space to cut interest rates in August and November.

Rates in New Zealand may now appear to have bottomed, and perversely this may keep downward pressure on the currency as the market begins to see this as a threat to household confidence and the housing market.

Rising Bank funding costs set to tighten lending conditions

The other vulnerability for the New Zealand and Australian economies in a rising global interest rate environment is that their banks still rely on foreign borrowing to finance a significant portion of their loan assets, dominated by mortgage loans.

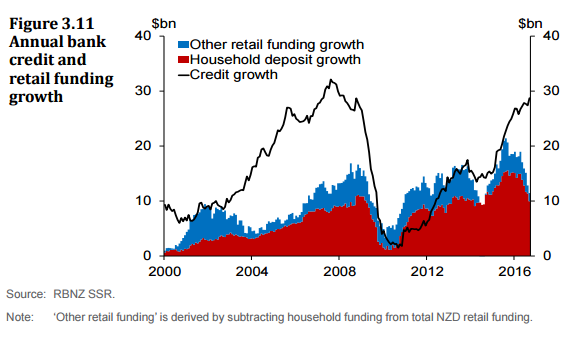

The RBNZ FSR noted that 30% of bank funding in New Zealand is from wholesale markets, (i.e. that portion not covered by deposits). And around 60% of this wholesale funding is raised offshore.

In recent years, since 2014, New Zealand banks have resumed expanding their reliance on offshore market-based funding (chart below).

As the cost of foreign funding sources begins to rise, banks are likely to become less eager to grow their mortgage books; applying tighter lending standards.

Since the GFC banks have been required to adhere to rules requiring longer-term funding. As such, their cost of funds is more driven by longer-term rates than was the case pre-GFC. As longer term rates offshore rise, they raise NZ bank funding costs. This, in turn, tends to increase the cost of funds onshore as banks compete for scarce onshore funding markets, including term deposits.

Banks then aim to recoup these costs, maintain their Net-Interest-Margins (NIMs), by raising mortgage lending rates, including on short-term or variable rate mortgages, affecting household finances.

In a falling global bond yield environment, apparent for the first three-quarters of this year, bank funding costs were falling, resulting in easier domestic monetary conditions. Banks were competing for mortgages by lowering rates, boosting household finances and confidence.

This trend is now reversing; even before the RBNZ considers raising rates, financial conditions in New Zealand and Australia are starting to become tighter, as banks respond by removing discounts on mortgages, apply tighter lending standards and raise mortgage rates in response to higher global bond yields.

It may be relatively subtle at this stage, but with high levels of household debt leverage, it can begin to impact on economic confidence relatively quickly.

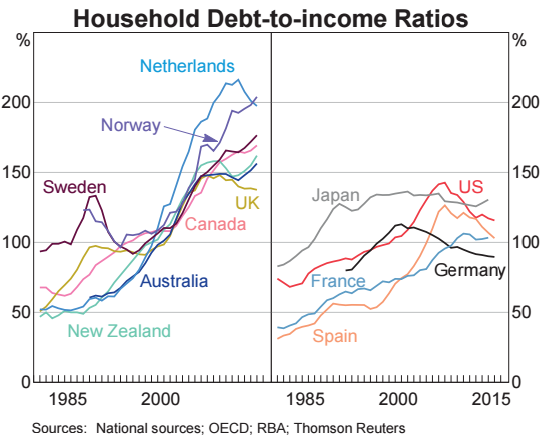

Debt headwinds ease in the USA and pick-up in Australia

The RBA 14 October Financial Stability report presented the following chart of Household Debt-to-Income ratios. High growth has been experienced in Scandinavian countries, Australia, New Zealand and Canada. Tax laws in these countries may have encouraged more household leverage, along with relatively easy bank lending conditions, even as these countries’ regulators increased macro-prudential measures to contain credit growth.

On the other hand, the USA has reduced household leverage since the 2008 GFC more than most other major countries; this process has frequently been described as a headwind that slowed the USA economic recovery relative to previous episodes. Countries like Australia and New Zealand have experienced faster economic growth in recent years fueled by strong credit growth.

However, in a rising interest rate environment, the tables may be turned in favour of faster USA economic growth, facing fewer headwinds from higher interest rates than other more highly indebted countries.

Australian and New Zealand banks are highly interconnected

Financial Stability Risks in Australia and New Zealand are highly interconnected because the four largest banks in Australia are the major owners of the largest banks in New Zealand. New Zealand bank assets account for around 10% of Australian bank assets. Banks in Australia and New Zealand have very similar balance sheets and operations, dominated by mortgage lending accounting for over half of Australian bank balance sheets.

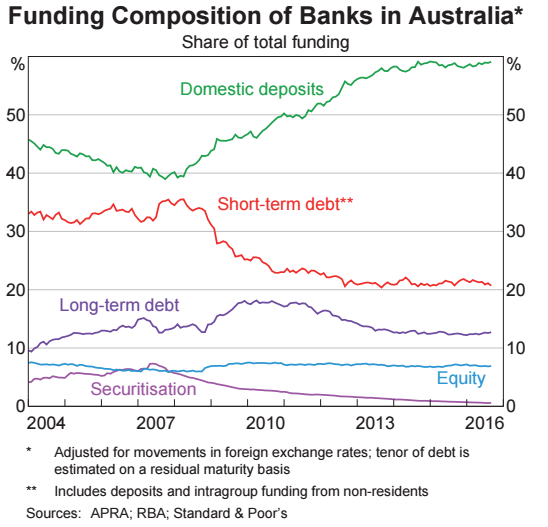

Australian banks have a similar reliance on offshore wholesale financing to New Zealand banks. Over 30% of funding is in wholesale funding and much of that is from foreign sources.

Regulators have forced Australian banks over recent years to move toward longer term financing. This has intensified this year and is expected to continue in 2017 ahead of the introduction Basle III Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) in January 2018.

This process may have helped reduce bank funding costs through the first few quarters of this year in a falling global yield environment. However, higher global yields in Q4 point to rising bank funding costs ahead.

Australian banks have been reported recently tightening lending condition and raising mortgage rates modestly.

CBA, NAB, Westpac turning up heat on property buyers – AFR.com.au

Mid-tier banks say calm restored in home loan market – TheAustralian.com.au

Ratings downgrade predictions in Australia

S&P ratings agency placed Australia on a negative outlook in July, threatening to downgrade its AAA rating. Since then weaker GDP growth and political inertia have generated increasing speculation that Australia would be soon downgraded. There was much focus on the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook (MYEFO) delivered by the government on Monday as a key determinant of the S&P rating decision. Few anticipated that it would trigger a downgrade, but a consensus is developing that a downgrade will follow the May budget next year.

The resurgence in coal and iron ore prices this year has helped underpin the budget outlook, but few see the rebound in prices as sustainable, and the government decided to forecast a fallback in commodity prices over its 5-year projection. On the other hand, it still forecast a pretty optimistic assessment of income growth in coming years.

The $25b commodity price gift that Scott Morrison rejected – AFR.com.au

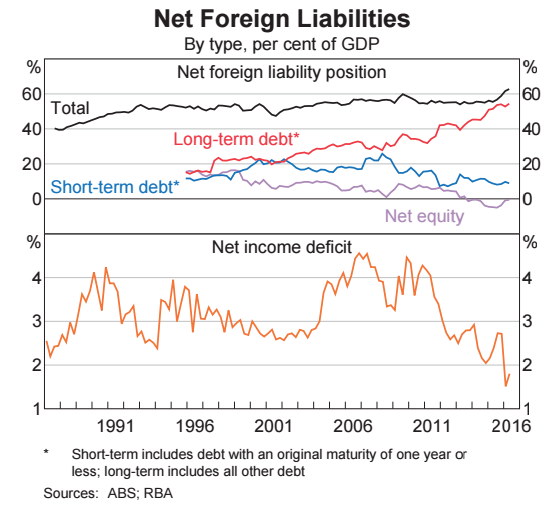

However, the ratings pressure in Australia is not driven by government finances. Certainly, S&P are looking for the government to demonstrate a credible plan to return to budget surplus, but the main issue is the high level of household debt, contributing to relatively high national foreign debt that rose in the last year to above 60% of GDP.

S&P also revised the outlook for Australian banks to negative in October. The big four banks have strong ratings of AA- in part because of perceived high level of government support. A sovereign downgrade is expected to flow through to Australian banks and, therefore, is likely to add to their cost of funds in international wholesale markets. As such, a government ratings downgrade is assumed to generate some flow-through to higher mortgage rates paid by Australian households.

AAA rating cut will push up home loans – AFR.com.au

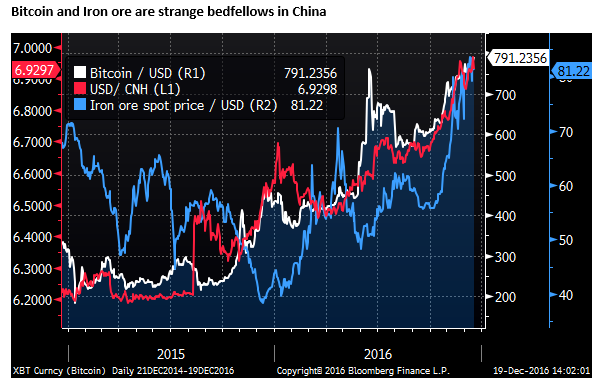

Bitcoin and Iron ore acting as currency alternatives for Chinese investors

Stronger Chinese growth this year and capital outflow to the Australian and global property market has been a source of support for the Australian commodity prices and the AUD this year.

However, the AUD exchange rate has been reluctant to take on board the rebound in commodity prices at face value probably because Chinese growth has been fueled by easy credit conditions worsening China’s already stretched levels of debt. Furthermore, the persistent capital outflow from China and a weak CNY point to weak domestic confidence in Chinese financial stability.

Many suspect there is a highly speculative element in the surge in Chinese commodity futures prices this year. The rise in iron ore prices is inconsistent with a build-up in stockpiles at Chinese ports.

One thought is that controls that limit the flow of Chinese capital out of China encourage Chinese people to buy commodities to escape exposure to CNY.

The strange performance of Bitcoin, the virtual cryptocurrency, may be another version of this distortion. Despite the broad rally in the USD in recent months, Bitcoin has continued to strengthen against the USD and appears highly correlated with the performance of USD/CNY.

It seems that Chinese investors, looking to escape the CNY, but with limited capacity to buy foreign currency, have bid-up the price of bitcoin as an alternative.

It may be the case that a weak outlook for their own currency and capital controls to limit sales of CNY may be similarly contributing to a rise in iron ore prices and other commodities.

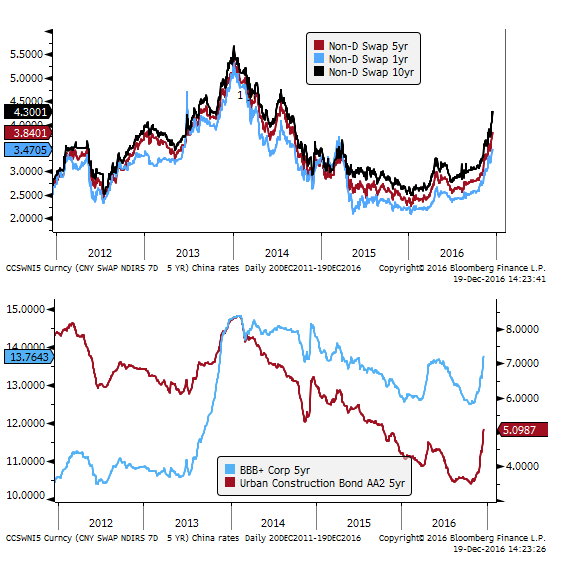

The economic data in China continues to support the notion of a reasonable demand for commodities. However, the recent broad-based surge in Chinese interest rates and yields points to developing financial stress.

Rates have risen abruptly in the last month across the yield spectrum to highs since 2014. This may reflect tightening liquidity conditions deriving from capital outflow and/or increasing reluctance within China across institutions to lend to each other beyond the very short term. The Chinese government may be able to control the rise in rates and yields by injecting liquidity and instructing policy banks to lend to other institutions. Nevertheless, higher rates imply tightening credit conditions that may undermine economic growth in China and send a message to global investors that financial stability risks are more elevated.