Risks for AUD and NZD coming to the surface

The USA fired off its biggest missile yet in its trade war with China and has rolled up more artillery. There is little doubt that they are in for the long fight and this poses significant downside risks for Asian markets. AUD has been a proxy for tariffs and rebounded on Tuesday, in-line with a bounce in Asian currencies and equities. But the trade war suggests this reprieve may be short-lived. If you close one eye, the Australian economy is performing well, and the AUD looks cheap. But if you open both eyes, the downside risk coming from China, housing and the next election is large. The falling Australian housing market may bring to the surface more problems for banks over past lending practices. New Zealand economic survey data is pointing to a weak second half and rising risk of significant further RBNZ rate cuts.

Trade War – what is it good for?

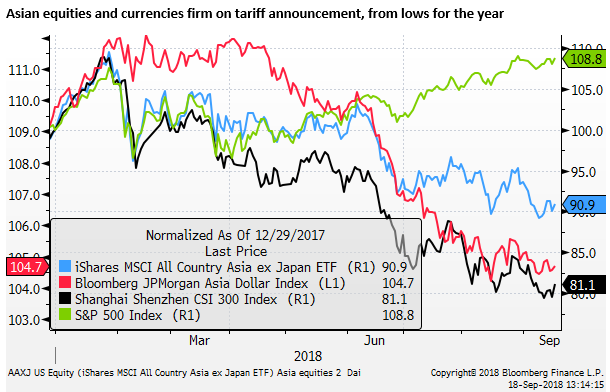

The long-awaited next batch of US tariffs on Chinese goods has been announced. Asian currencies have taken this in their stride, most rising on Tuesday after the announcement. After several months of declines in emerging markets, investors appear to have significantly reduced exposure to the Asia region and were essentially prepared for the tariff news.

However, the tariff news is hardly good news. The US administration has announced tariffs at the harshest end of expectations, increasing to 25% from 10% at year-end on $200bn in goods, and preparations to extend to a further $267bn in goods if China retaliates; which China has said it will. Last ditch trade talks led by US Treasury Secretary Mnuchin appear now likely to be called off. As such, this is hardly a time to move confidently back into Asian regional assets.

The debate will continue over how much these tariffs will affect commerce and economic activity in China, the USA and the rest of the world. But the broader message is that the US administration appears to have a firm policy of attacking what it sees as unfair trade and industry policy in China and is happy to use the blunt tool of tariffs. This points to a long-lasting threat to industry in China and additional inflation risk in the USA.

The Chinese economy is already facing challenges as it deals with excesses in its domestic financial system. The potential disruption to global supply chains may impact on global trade and global growth.

Rising US interest rates and yields appears to have contributed to financing troubles in several emerging market economies. The tariffs may place further upward pressure on inflation expectation and yields in the USA, with negative feedback to the global economy. As such, the US tariffs policy should tend to undermine confidence in Asian and other emerging market economies.

The risks to China may increase if the USA now pursues a more closed NAFTA agreement that tends to discourage Chinese investment and trade into Canada, Mexico and the USA. The US administration may also use inducement of better trade relations with the EU and other nations if they support its actions to pressure China to reduce its state support for strategic industries.

China, on the other hand, may hope that it can pressure the US to remove tariffs by targeting companies, sectors and states in the USA designed to undermine US public support for the Trump administration. It may hope that a poor showing by the Republicans in the mid-term elections might weaken support for Trump and his tariffs.

The twists and turns from here may continue, and the risk is high that an on-going trade war plays badly for business confidence in China, the USA and globally. At this stage, we sense that China is the most vulnerable, threatening the stability of the Chinese financial markets and currency.

AUD acting like a tariff risk barometer

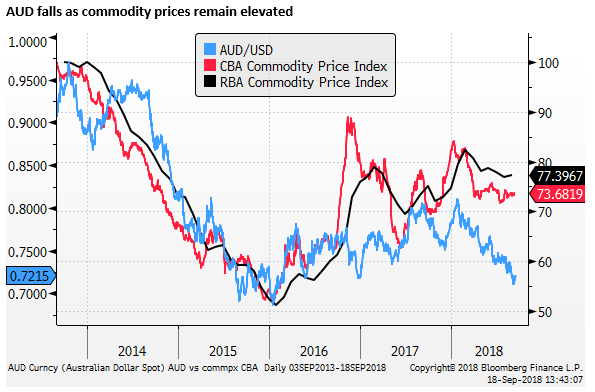

The AUD has tended to act more as a risk barometer for China and tariffs in recent months. Falling significantly, even as its domestic economy strengthened to be growing more consistently above-trend in the last year, further reducing spare capacity in the labour market and bringing the RBA closer to a date when it might consider raising interest rates.

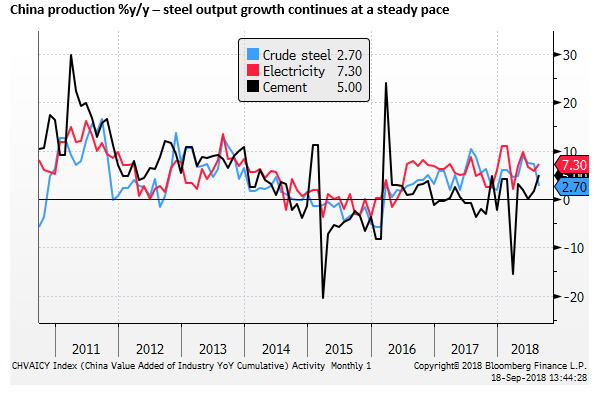

If you cover one eye, the Australian economy is on a road to normalization, and the AUD might seem cheap. Part of that apparent strength is the stability in Australian export prices. Chinese steel production has remained relatively sold despite a gradual slowing in the Chinese economy. The most recent Chinese residential property market activity has gained momentum, supporting the outlook for steel demand.

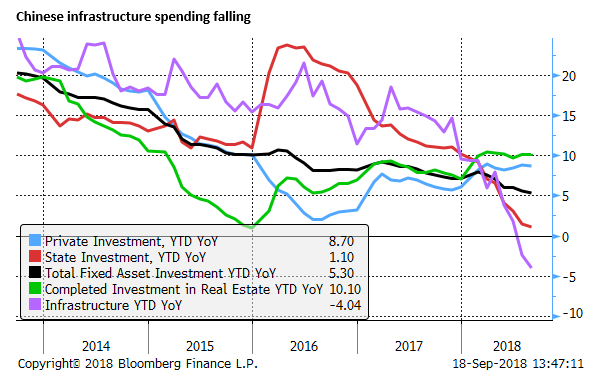

Chinese infrastructure activity has been falling surprisingly fast this year, but observers, including the RBA, expect China to ramp-up infrastructure investment to help support the economy. Growth risks from tariffs may encourage policymakers in China to use fiscal and monetary policy to boost domestic demand, supporting import demand from Australia. It is possible to construct a favourable scenario for the AUD notwithstanding the larger more sustained threat to China’s economy and financial markets arising from US trade policy.

Significant risks weighing on AUD

However, if you open both eyes, there are some significant risks for the AUD that may continue to weigh on the currency. In fact, they provide a scenario where the AUD could yet fall substantially.

The first of course is China and the down-draft that may arise from weaker Chinese financial assets and currency.

A second is if broader weakness in the Chinese economy does spill over to Chinese steel and related commodity prices.

A third is the weaker Australian housing market and the pressure being exerted on banks to tighten lending standards in the wake of the Hayne Royal Commission into misconduct in the financial services industry.

A fourth in a likely change in government in Australia at the next general election expected by May next year. A change to a Labor Party government raises downside risks for the housing market, pursuing a policy of removing negative gearing and halving capital gains tax concessions for investments in housing.

Financial stability risks in a falling housing market

An article in the Australian Financial Review last week, quoting a lawyer working on “test cases” against banks, I think, highlights the risks that excesses in the Australian mortgage market may be exposed and threaten financial stability in Australia.

Banks face years of litigation, billions in costs after Hayne; 16-Sep – AFR.com.au

It has long been argued by regulators, rating agencies, and analysts that the Australian banking system is well capitalised, safe and maintains strong lending standards. However, the Hayne Royal Commission has revealed what appears to be significant weaknesses in the assessment of loan quality. The mortgage market has incentivised maximising loan value and inflating the capacity of borrowers to repay.

This has never been a problem in a rising property market. But, as has happened many times in financial crisis events in other countries, the extent of problem loans and systemic weaknesses do not reveal themselves until the market is falling.

The AFR article highlighted tends to rhyme with history. It suggests that litigation against banks is likely to increase in a falling property market where borrowers begin to feel they have been duped into borrowing too much.

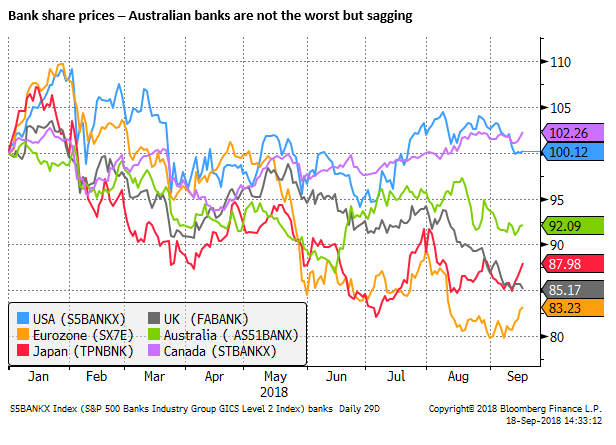

The Hayne Royal Commission has provided the ammunition for class action litigation and a falling property market increases the risk that it is fired at banks. Banks in response have, and are likely to further, tighten lending, creating a snow-balling inter-connecting deterioration in confidence in housing and bank profitability.

It is a matter for debate how vulnerable the Australian housing market is and the quality of lending in the market. It is probably nowhere as bad as the US sub-prime crisis. But it may not be as good as the RBA and regulators have assured us either. It is likely, in our view, that it will appear worse in a declining housing market, as this will bring to the surface problem loan areas.

On the whole, banks have endeavoured to lend to people with solid incomes and fallout to banks’ profitability from a housing downturn is unlikely to generate severe crisis-like problems.

But it is also true that credit availability has been relatively easy compared to history and other counties for many years, the envelope has been stretched and corners cut in determining capacity to borrow. Easy credit conditions have helped pump up housing prices rapidly in recent years to new records, not least because interest rates have been cut to record lows.

Credit conditions have now been tightened. Borrowers for housing investment, in particular, are facing higher costs as many are forced from interest only loans onto principle and interest loans as part of the regulatory effort to address excesses in lending practices over the last 5 to 10 years.

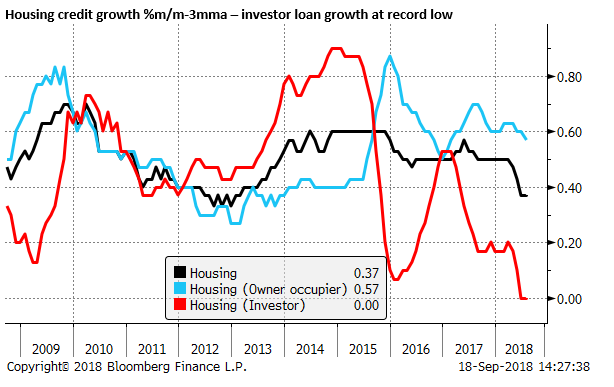

The housing market is now in a moderate downturn, investor credit growth has fallen to a record low (zero% m/m-3mma). In a falling housing market, tightening credit, and potential government policy tax changes afoot, the risk is that investor credit will soon decline outright.

A potentially bigger risk for banks is that borrowers who happily accepted high LVR loans in a rising market, now claim they were pushed into borrowing too much, and join class action lawsuits against the banks, seeking financial damages for buying real estate at above current market prices. This would threaten to further sour the housing market and bank share prices, and perhaps lead to excessively damaging tightening in credit conditions.

New Zealand economy surveys weak

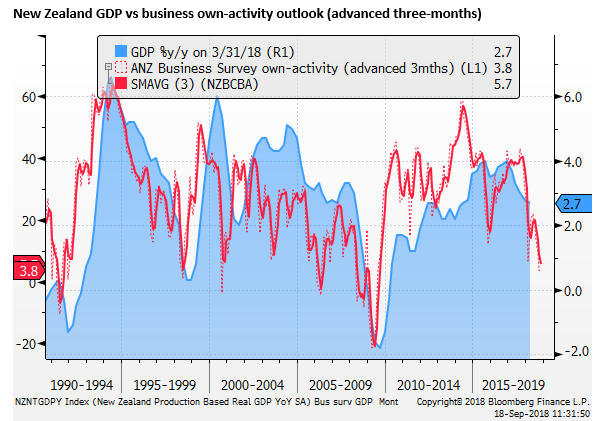

While the Australian economy has been showing solid momentum, the New Zealand survey data is pointing to weaker (significantly below trend) growth, increasing the risk that the RBNZ cuts rates again to new record lows.

On Thursday, NZ GDP data are released, and the partial indicators for the quarter are reasonably solid, such that the market is expecting a 0.8% q/q rise in Q2. But the annual growth is expected to slow from 2.7% to 2.5%y/y, which would be the lowest growth rate since Q4-2013, running below the perceived trend/potential growth rate somewhat above 3%.

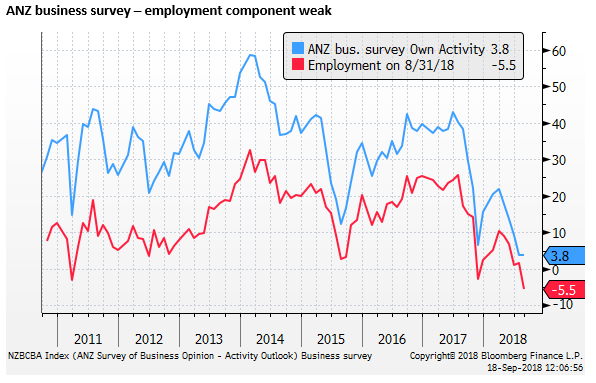

The RBNZ has been forecasting a recovery in growth from the slowdown in the last few quarters, but survey data points to further slowing in the second half of the year. The chart below shows the closely followed ANZ business survey own-activity index at a low since 2009.

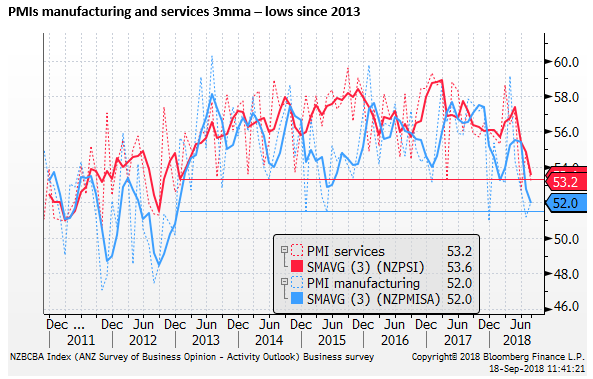

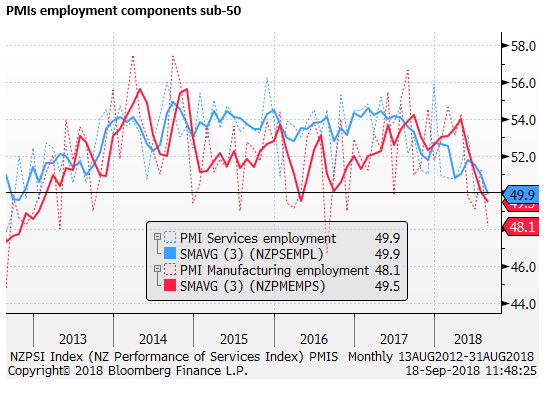

The weakness is apparent in the PMI surveys for both manufacturing and services; both at their lowest three-month averages since 2013

The components in these surveys are equally weak; the important labour market components even more so. The three-month averages for the PMI services and manufacturing employment components are both below the 50 level.

The ANZ business survey employment component fell to its lowest level since at last 2010, pointing to a significant slowing in job growth.

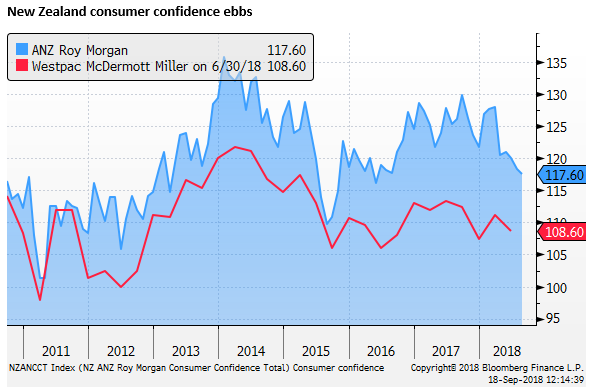

New Zealand consumer confidence has not deteriorated as much, but it too appears to be significantly weaker since Q1.

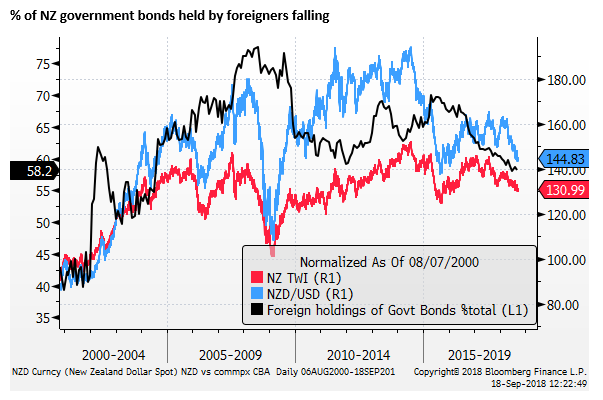

Foreign demand for NZ bonds around lows since 2004

New Zealand yields are no longer so clearly high enough to attract foreign demand. The monthly series on foreign holdings of New Zealand government bonds has fallen steadily in recent years to around its lowest share of outstanding since 2004.

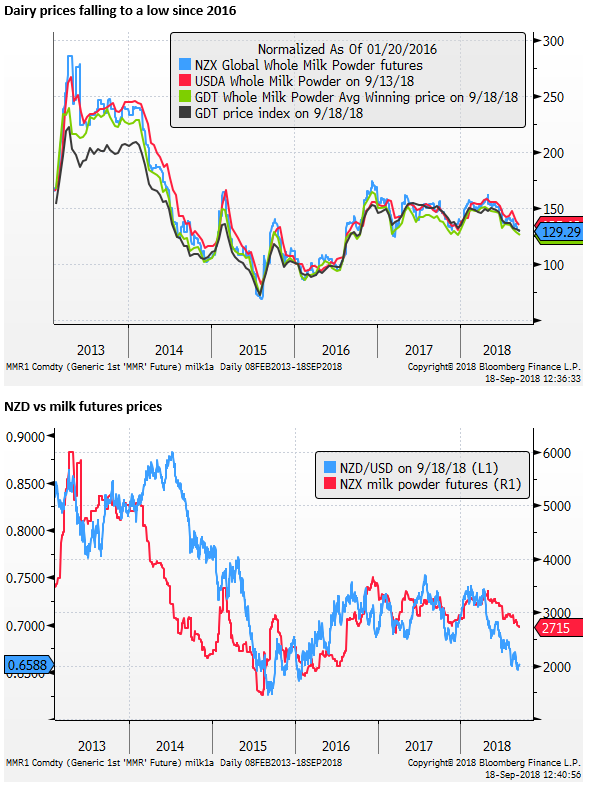

Dairy prices falling

New Zealand dairy prices have also been declining since around mid-year. The NZ dairy cooperative Fonterra owned Global Dairy Trade auction index has fallen to a low since 2016.

While the level of commodity prices might still justify a stronger NZD, falling dairy prices in recent months, combined with a negative and falling yield advantage may keep downward pressure on the NZD/USD.

RBNZ said they would cut rates

The growth outlook is beginning to look more like the RBNZ’s growth risk scenario, where GDP growth stays below 3% in the coming year. In which case the RBNZ said in its August MPS that “As it becomes clear that growth is not picking up as expected, the OCR would need to be reduced by around 100 basis points.” (from 1.75% currently).

As it stands, the market is pricing in a gentle downward slope for expected cash rates, with the cash rate priced at 1.68% in 12-months (about one-quarter of a 25bp rate cut).

Considering the weakness in business and consumer surveys, it seems that the market may be underpricing the risk of rate cuts.

The RBNZ is unlikely to change policy at its meeting next week. But it may begin to wonder why spending programs by the new government, including the various support packages for families that began in July this year, have not done more to bolster confidence and spending.