When does political risk matter in New Zealand? EUR now a high beta currency

EUR failed to rise on upbeat political developments. It appears that EUR is trading more like a high-beta growth currency; unusual for a low yielding current account surplus currency. EUR has probably benefitted from unhedged equity inflow and is vulnerable to a correction in equities. The market is also net long EUR and, in a risk-off environment, position squaring and deleveraging is likely to see EUR selling. The NZD is vulnerable to some evidence that the, until now, strong New Zealand economy is peaking; GDP later this week may underwhelm. The market also appears too complacent that the National Party will be returned to power in the 23 September election. Anti-immigration NZ First may return as a king-maker and has more in common with the Labour Party, which has tougher policies on housing investment. The Bank of Canada have shown surprising optimism in the face of increasing risks and have wrong-footed the market.

EUR trading like a high-beta currency

EUR is trading like a high-beta currency, more positively correlated with equity performance and investor confidence than would normally be the case for a low yielding current account surplus currency.

In a low yield environment globally, capital appears to have been drawn more to equities in general, and investors have paid less attention to interest rate differentials and hedging costs.

EUR has probably benefitted from unhedged equity inflow and is vulnerable to a correction in equities. The market is also net long EUR and, in a risk-off environment, position squaring and deleveraging is likely to see EUR selling.

If the correction in tech stocks in recent sessions builds and undermines equities more generally it is possible to see a bigger correction lower in the EUR, despite its improving economic and political outlook.

The Euro STOXX index peaked on 5 May, just ahead of the second round of the French Presidential election of Macron. European equities have struggled in the last month, and this may help explain some stalling in the EUR in recent weeks.

When does New Zealand political risk kick in?

New Zealand faces a general election on 23 September. The National Party has governed for three terms since 2008. It will be the first election for Bill English as Prime Minister, after he replaced John Key on 12 December 2016.

There are a number of complexities in the first past the post system, requiring voters to vote both for a candidate in their local electorate and make a party vote (Mixed-member proportional representation MMP).

New Zealand elections are hard to predict. A key point of uncertainty is the 5% threshold. If a party wins 5% of the party vote they receive a number of seats based on the proportion of the vote they received. As such, parties on the cusp of 5% can change the result depending on which side of the 5% threshold they fall.

Parties can gain a seat if they win the vote in an individual electorate, even if they receive less than 5% of the national party vote. And if they get an electoral seat, then their percentage of the party vote can add more seats, even if it is less that the 5% threshold.

There are typically 120 seats in the single house parliament; 71 seats are directly elected electoral seats, and the remaining 49 are allocated based on the share of the party vote. But if one party obtains more electoral seats than reflected in their share of the party vote, then more than 120 seats are allocated to ensure all parties get their share of seats based on the party vote.

There are 7 Maori electorates (based on the proportion of voters that choose to be on the Maori electoral roll). That is 7 of the 70 electoral seats. These overlap the standard electorates and elect representatives voted in by people that identify as Maori, indigenous New Zealanders. The Maori Party currently holds one of these seats, and has two members of parliament (one allocated due to the party vote). The Labour party hold six of the other Maori seats.

The governing National Party, led by PM Bill English, currently holds 58 out of the current 119 sitting members (less than 120 due to resignations, including former PM John Key).

The opposition Labour Party has 31 seats, their natural ally on the left side, the Green Party holds 14 seats.

The nationalist or populist party that often acts as a king-maker in parliament, NZ First Party, holds 12 seats.

The ruling National Party holds the balance of power in parliament with support from the ACT party (1 seat, right-winged), the United Future Party (UFP) (1 seat – centrist) and Maori Party (2 seats – left). It needs at least two additional votes to make the 60 seat majority.

On current polling, the National Party is again not going to get an outright majority with 46% of support, losing some ground since the last election. Labour looks likely to pick up some extra seats polling 30% of the vote. Greens are stable at around 12% and NZ First has improved its position somewhat with 10%.

On these numbers, NZ First may return as king-maker in the election; Nationals may not be able to cling to power with the support of the single-member ACT and UFP.

Working against the Nationals is that they have held power for nine years and three terms and, like many democracies, the people often want to give the other lot a go.

NZ First was founded and is led by the enigmatic Winston Peters who knows how to tap into discontent with the major parties. He is an opportunist that will deal with either side of politics to gain a ministry and/or significant policy commitment. NZ First is often against immigration, and this has become a much more contentious issue, running at record levels for a number of years, placing upward pressure on house prices and strains on infrastructure.

To date, the NZD is showing no sign of political risk. The market may be too complacent in thinking that the National Party will retain government. And it is showing no concern that if it does, it will have to deal with NZ First that would make its government more unstable and may require some curtailment on immigration.

If Peters’ NZ First holds a balance of power, he will almost certainly squeeze both sides of politics and threaten to choose the other side if he doesn’t get something in return.

Once the market begins to contemplate that Labour could form government with Greens and NZ First, it is likely to weaken demand for the NZD, raising policy uncertainty, and seen as risking growth in the economy.

As it stands, Labour is closer to NZ first on immigration policy. On its website it says it will “ban foreign speculators from buying existing homes, and “tax property speculators who flick houses within five years”, and end negative gearing tax concessions for house investors.

Addressing housing affordability in a major issue in the upcoming election. Both major parties have a plan to fund building more houses. But the Labour Party proposals appear to pose a bigger risk for house prices and would potentially contribute to a bigger correction in the housing market, with negative implications for the broader economy.

National Party website: https://www.national.org.nz/

Labour Party website: http://www.labour.org.nz/

New Zealand economic growth slowing

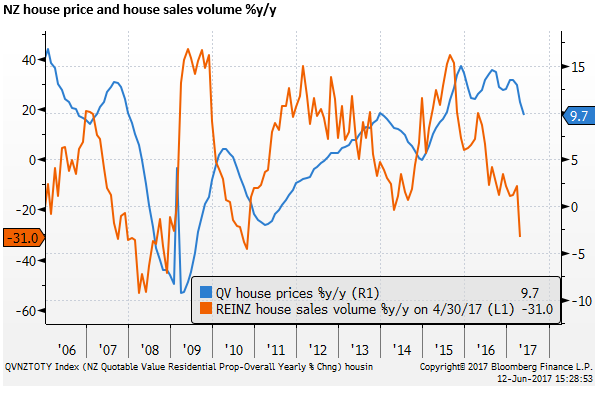

The housing market in New Zealand has been weakening since late last year with tougher macro-prudential policies and more conservative bank lending practices as banks witness regulatory pressure on parent companies in Australia.

The QV house price index has slowed from 13.5%y/y growth in February to 9.7%y/y in May, a low rate of growth since June-2016. REINZ house sales fell 31%y/y in April, a low since 2010 (May data are due this week).

The New Zealand economy has been growing at an enviable rate above perception of potential, albeit with the help of rapid immigration that has added to broad demand in the economy, but helping hold down wages.

However, more recent reports show evidence of peaking in economic activity.

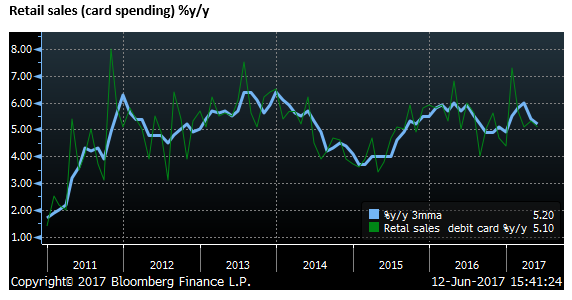

Retail spending fell 0.4%m/m in May, well below +0.2% expected. Annual growth slowed to a still solid 5.2% 3mth-yoy, but down from the recent peak of 6% in February

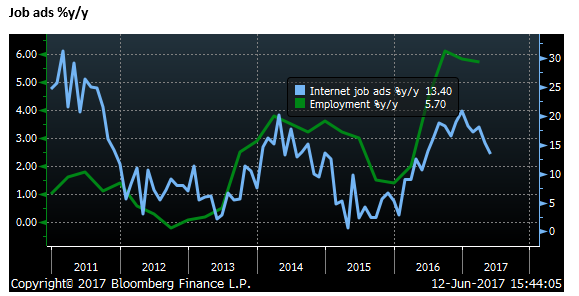

Job ads fell 0.6% in May; annual growth slowed from a recent peak of 21%y/y in December to 13.4%y/y in May.

Manufacturing activity volume (feeding into the GDP report on Thursday) fell 0.3%y/y in Q1, following a 2.0q/q fall in Q4 (revised weaker from -1.8%q/q). The fall was driven by a deep fall in meat and dairy product manufacturing.

The volume of building work put in place in Q1 also fell 3.4%q/q in Q1 also pointing some drag on Q1 GDP.

The market is predicting GDP of 2.7%y/y later this week, unchanged from Q4, but given these recent reports, the risk appears to be a weaker outcome.

Bank of Canada blindside market

The CAD has surged on Monday following a speech by BoC Deputy Governor Wilkinson. The BoC has a history of swinging their view and catching the market off-guard.

Canadian two-year rates have surged by around 12bp since Friday. Suddenly the 12 July policy meeting appears in play for a possible rate hike; albeit still a modest 13% chance. And a 60% chance of a 25bp hike by year-end.

Rates have been at a record low of 0.5% since mid-2015, cut twice in early 2015 from 1.0% in response to weaker oil prices crunching energy sector investment. The optimistic tone struck by Wilkinson included a recovery in business investment in the energy sector.

It is interesting that the BoC would flag a tightening bias just at the time when energy prices have ebbed from recent highs and competition from the US energy sector is growing. And threats to the Canadian economy that arise from tighter lending conditions and regulatory and tax policy that may dampen housing market activity.

Nevertheless, policy makers are impressed by broadening evidence of robust activity. Wilkinson said that the 3.7% q/q saar GDP growth was “pretty impressive”.

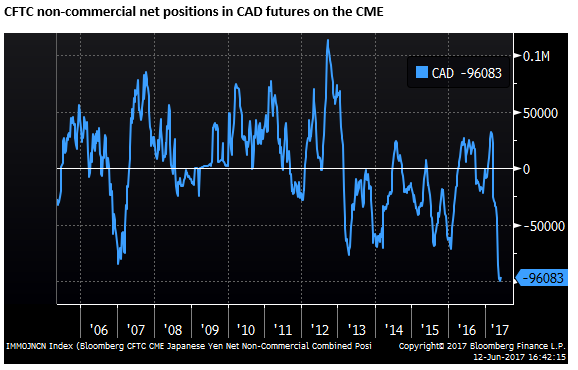

It does appear that the shift in tone on policy has caught the FX market with a significant net short CAD position.

From our viewpoint, we are somewhat surprised that the BoC has expressed so much optimism in light of significant uncertainty related to energy prices, its own housing market, and political uncertainty in the USA, including threats to NAFTA. But there has been stronger economic indicators and these at face value justify a BoC tightening bias.

USD/CAD has broken a recent uptrend, Canadian yields have jumped sharply, and market positioning has been caught out well short CAD. This creates a risk of further significant gains in CAD near term.

The market may look for parallels with AUD and NZD. However, we expect both these central banks to be much more cautious about adjusting their policy statements. Both tend to prefer a weaker exchange rate and maybe more concerned by vulnerabilities in their housing markets and household debt.