An RBA rate cut next week is the smart move; Fed firmly on hold

The RBA should cut rates next week to signal that its inflation target still matters. Slumping inflation expectations over the last six months, and shifting global central bank focus to address low inflation outcomes, make it more imperative for the RBA to act. Its patience with low inflation was appropriate when the housing market and associated financial stability risks were rising; this is no longer the case. Global and domestic economic indicators have already shifted the balance of risks towards a weaker labour market. Waiting until after the election or until actual labour data soften before cutting risks more damage to the RBA’s credibility in the medium term, than acting now.

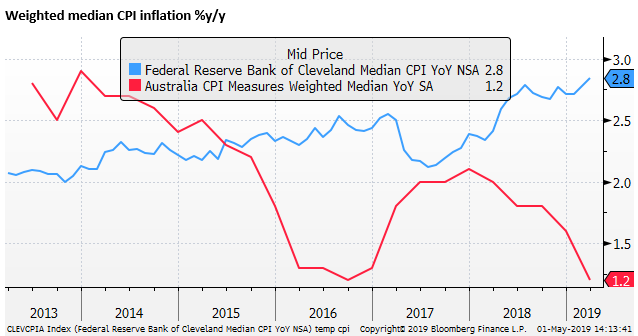

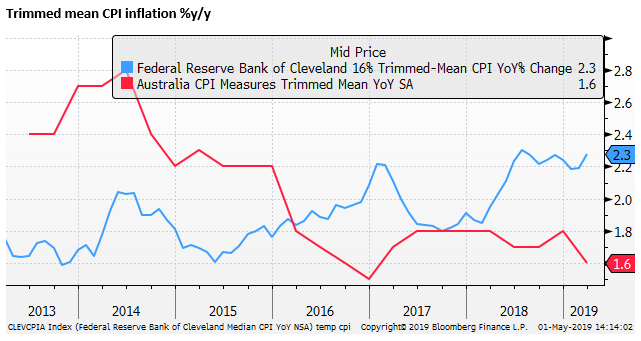

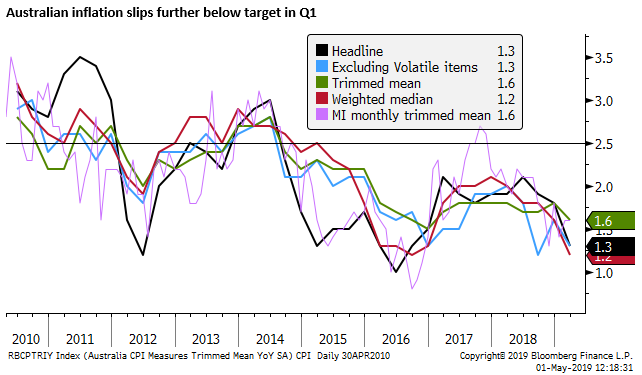

The Fed emphasised a rates on hold view today, batting away pressure to address the recent fall in inflation. Chair Powell highlighted the trimmed mean inflation data that shows inflation still steady at around 2%. Using statistical measures of underlying inflation there is a clear divergence in inflation trends in the USA (rising) and Australia (falling). With rates firmly on hold in the US, a rate cut by the RBA might be expected to push the AUD well below 0.70, something the RBA would welcome to help lift inflation expectations in Australia.

A live meeting

The RBA rate decision next week (7 May) is a live meeting, where the Board is expected to debate whether it should cut rates or not. That debate is likely to be raging inside the RBA as staffers tee-up their recommendation to the board. The market is pricing about a 45% probability of a rate cut.

It had been close to a 60% probability immediately after the weaker CPI data released last week, but has eased back under 50% as some influential RBA watchers, including the Sun-Herald’s McCrann and Westpac’s Evans said to the god of monetary policy – “not today.”

The argument in favour of a rate cut, and the reason why, in my view, the RBA should cut rates, is that not to do so would threaten credibility in its inflation targeting regime, and potentially permanently lower long-run inflation expectations, making it harder to achieve target-inflation in future.

(The RBA targets inflation in a 2 to 3% range over the medium term. In the past it has made a virtue of averaging 2.5%; implying this is point target).

It also appears that the RBA has little to lose from cutting rates at this meeting. There is little risk that it will spark a set of conditions where inflation will rise too much and force a rapid reversal of the cuts, neither would it trigger a sudden run-up in household borrowing and worsen financial stability risks.

The ‘Not Today’ viewpoint

The viewpoint that the rates will be held steady at this meeting leans heavily on the notion that the message from the RBA in its recent statements is that it is closely watching the labour market that has remained relatively strong.

The strength in the labour market underpins the RBA’s projection that wage and income growth will increase and in time, albeit some years away, gradually lift inflation back to target. The RBA has displayed unusual patience in allowing a prolonged period of below-target inflation and projecting a slow return to target. The RBA has been less focused on inflation outcomes, accepting inflation may remain stubbornly low for a variety of global structural reasons, and more focused on the underlying balance of supply and demand in the economy.

The ‘not today’ camp argues that while the lower inflation outcome supports their view that eventually, in some months ahead, the RBA is likely to cut, it does not provide sufficient reason for the RBA to change course next week.

The ‘not today’ camp has pointed to the sentence in the April RBA policy meeting minutes that said, “Members also discussed the scenario where inflation did not move any higher and unemployment trended up, noting that a decrease in the cash rate would likely be appropriate in these circumstances.” The ‘not today’ camp argues that while the first part of this statement, “inflation did not move and higher” may appear to be met, the second part “unemployment trended up”, has not been met. As such, if the RBA were to stick to its messaging, it would not rush to cut at the 7 May meeting.

Some seasoned RBA watchers think that the RBA would be reluctant to change policy without first changing its messaging, and anticipate that it will use the May meeting to establish a clear bias to cut rates, allowing them the basis from which to cut in coming meetings, especially if there is any hint of momentum waning in labour market indicators.

Furthermore, coming within two weeks of a close national election (18 May), where there is a high probability of a change of government, the RBA would be reluctant to inject itself into the political debate by cutting rates.

No doubt these are fine reasons to expect the RBA to refrain from a rate cut at the 7 May meeting.

Less Tactics More Game

However, my view is that the RBA is more likely to cut rates next week. The reasons not to cut are almost entirely tactical. Virtually every one of the RBA watchers that anticipate no cut still expects the RBA to cut in coming months.

If the RBA has changed its mind, then it should act. To not act potentially undermines its credibility in the long run, and risks a policy mistake by not easing policy rapidly enough, threatening to require much further policy easing in the future, to the point where it has to deal with the unintended consequences of NIRP and QE that have dogged central banks abroad.

There is no guarantee that the RBA will not have to suffer the trials of unconventional monetary policy easing in future, but more timely rate cuts now would reduce the probability that it might.

While acting before messaging a clear bias to ease policy might undermine its credibility a bit, and hiking in an election campaign opens it up to criticism, it will appear to lack integrity to hold back a month simply to allow time to adjust its bias and avoid the election cycle.

If a cut is needed and the RBA holds back a month until after an election it could be criticized for supporting the electoral chances of the incumbent government.

If the RBA does not cut at this meeting, then it would appear to need a new trigger to cut at a subsequent meeting, otherwise holding rates steady will appear cynically tactical. This means that it should then wait for unemployment to rise, or inflation to fall even further. In both cases, the RBA raises the risks that rate cuts are unnecessarily delayed, raising risks for the economy and the long term credibility of the RBA and its inflation targeting regime.

Inflation still matters

From my perspective, the low inflation outcome is sufficient reason to act. A cut in May, directly after the inflation report, sends a clear message that the RBA’s inflation target still matters.

The global winds have shifted towards lower embedded inflation expectations. Key members of the Federal Reserve have indicated that it might be necessary to target average inflation (ie. accept periods of above-target inflation to offset past periods of below-target inflation). Central banks have become more worried about falling inflation expectations and low inflation outcomes forcing them to have to resort to unconventional monetary policy more often.

Whereas the Fed was hiking rates last year, more focused on a tightening labour market, this year they are more focused on actual inflation. As such, further Fed rate hikes in the next year or so appear much less likely. This focus shift is likely to be filtering into the decision-making process at the RBA. It too should be moving towards being more focused on actual inflation (and the problem that it has been too low for too long, and in fact now falling again).

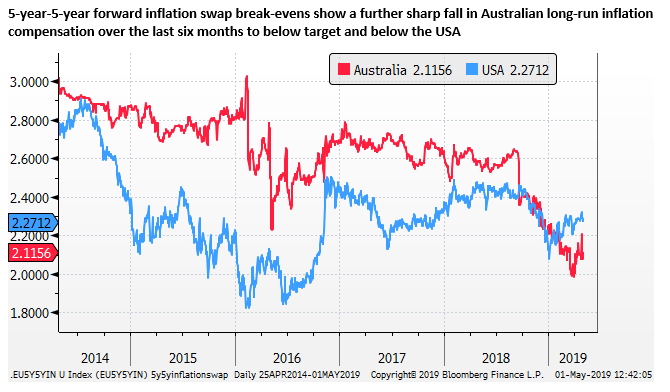

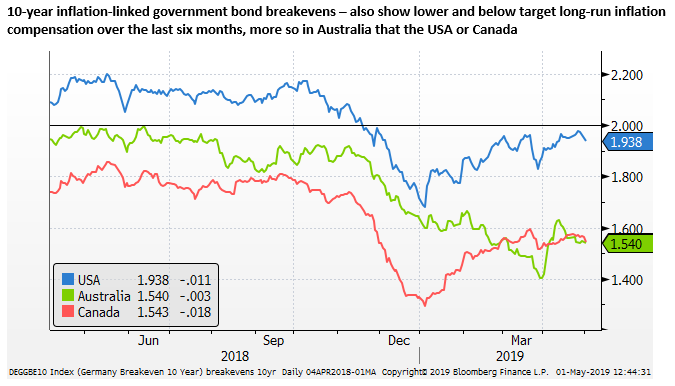

Market-based inflation expectations data also suggest that the RBA is facing a bigger problem. Long-run inflation compensation has dropped sharply in Australia, below that in the USA over the last six months, suggesting that expectations have become unanchored and dropped below the RBA’s target. This suggests that the RBA’s patience with below-target inflation is no longer appropriate, and it needs to respond to low inflation to signal its inflation target has not changed.

Labour market outlook has already deteriorated

In any case, the broader analysis of the domestic and global economic data suggests that the risks have already shifted towards a weaker labour market outlook. It may not have shown up in actual labour data yet, but it does not make sense to wait for labour data to soften anymore, especially if inflation and inflation expectations have fallen.

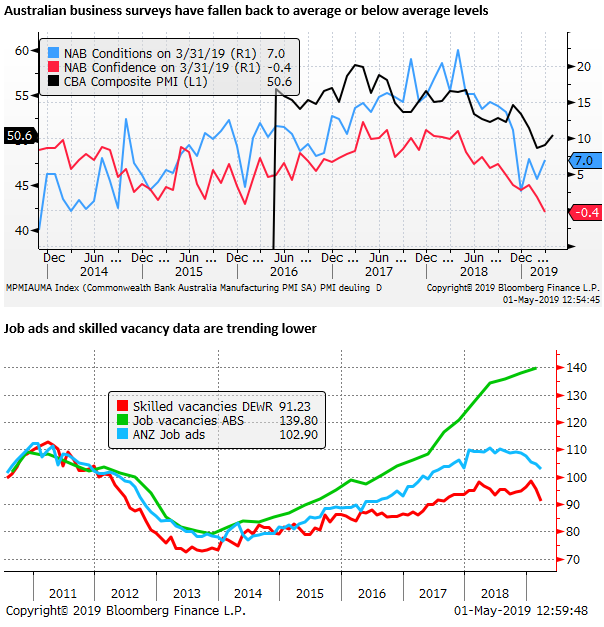

Australia business conditions and confidence are at best around trend levels. Some surveys are below average. Job vacancy data hit a new high in February (the latest data). But job ads and skilled vacancy reports show a declining trend for the last year in more up to date data.

Global industrial activity has slowed significantly and PMI reports for March/April show no evidence that it is about to recover.

The RBA has been clinging to the notion that employment data in Australia and globally are stronger than GDP and industrial activity indicators, waiting for the divergence between the two to be resolved.

It’s possible that underlying Australian and global growth remain more robust than GDP and industrial activity data, but there should be little doubt that the balance of risks has shifted towards softer employment data ahead. With dis-inflation risks now higher, the RBA should not ignore the risks of weaker employment growth any longer.

The RBA had already shifted to an implied easing bias

The RBA had already moved to contemplate rate cuts in April; while a bias to cut was not clearly stated, it was heavily implied. The RBA should not feel that a cut in May is inconsistent with its messaging. In its April policy minutes, it proposed a scenario for lower rates if inflation did not rise and unemployment did rise. However, it did not comment on what it might do if inflation actually fell. This outcome did not appear to be on their radar at that time. It is new information, arguably sufficient to act on an implied easing bias.

The Fed is firmly on hold

The Fed Chair Powell emphasized that the Fed is currently firmly on hold. He batted away multiple efforts from the media to address the possibility of insurance rate cuts to lift inflation from below its 2% target. He also batted away the one reporter that asked what the Fed might do if the economy over-heated.

The USD has strengthened and yields firmed in response to the press conference as the bias in the market had moved significantly towards possible rate cuts later this year.

The market is still seeing the risk of rate cuts, but these have been wound back as Fed Chair Powell failed to show as much concern over recent lower inflation outcomes than some may have been expecting.

This is consistent with our preview of the Fed meeting where we said that:

“The most-watched measures of US inflation have fallen, but there is a divergence in underlying measures and the lesser watched, but perhaps more indicative measures, have increased. The US labour market still appears tight, and the market and the Fed might be premature in writing-off inflation. However, the Fed would welcome higher inflation, and US rates are expected to remain stable for the foreseeable future.”

A reprieve for the EUR, but not a game changer; 30 Apr – AmpGFXcapital.com

Under repeated questioning on its response to the recent fall in inflation, Powell said that the declines appeared to be transitory, commenting on several special factors, including the new methodology in measuring apparel prices.

His predecessor, Yellen, described the fall in inflation in 2017 as transitory and pushed on with rate hikes in that year. She was right, with inflation rising again a year later.

Powell also highlighted the Cleveland Fed’s trimmed mean measure of underlying inflation, noting that it was above 2%, tending to support the notion that a few outliers were bringing down the more closely watched core measures of inflation that exclude the volatile food and energy components.

Indeed, we also highlighted this and some other alternative underlying price measures in our preview of the Fed meeting that suggest inflation is not as low as it seems.

We were somewhat surprised to hear Powell drag out the trimmed mean, but the persistent questioning over low inflation outcomes pushed him to reach deeper into his tool kit.

It is also worth noting that the transitory factors that depressed inflation in 2017 when Yellen was Fed chair were more broad-based and also depressed the alternative measures of underlying inflation. As such, Powell has even more reason to dismiss the recent fall in core CPI ex-food and energy as transitory and unrepresentative of underlying inflation.

There is a clear difference between inflation trends apparent in the USA and Australia at this time. Whereas these statistical measures of underlying inflation in the US are still close to target and trending up in some cases, they are well below target in Australia and have fallen recently.