RBA cut the obvious decision

We think the case is clear for the RBA to cut rates tomorrow and are predicting this outcome. The much lower core inflation reading, evidence of tightening bank credit conditions, some softening recently in credit growth, cooler job vacancies, a stronger AUD, some renewed doubts on China and timing of the 2 July election suggest the RBA needs to be decisive and get ahead of expectations. Consequently we see further weakness in the AUD and continue to favour gold as we discussed last week outlining risks in China that may spill over to global asset markets and the rebounding JPY that may push the BoJ toward more easing.

Politics is thick in the air

It’s an interesting week for the AUD ahead with the RBA rate decision on Tuesday a live meeting with the market pricing the odds of a cut at just over 50%. Adding juice to the week, the Government releases its annual budget on Tuesday evening local time. And this is a budget that essentially kicks off its campaign for the 2 July election.

Politics is thick in the air in Australia at this time with the polls showing the race is neck and neck between the ruling Liberal National Coalition (LNC) and the opposition Labor party. Housing is never far from the hearts and minds of Australians and it will play a part in the RBA policy decision and the budget.

A rate cut by the RBA would have to weigh-up the odds that it fuels further excess in housing. And the government will face off the opposition on housing taxation policy, with the opposition Labor party proposing reducing negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions for housing investors.

Walking a fine line on the budget

The Government budget is expected to be more heavily scrutinized by rating agencies as the government attempts to walk a fine line between supporting growth and providing a plan for returning the budget to balance that has been in deficit since 2007. There has been little progress in reducing the deficit from around 3% of GDP over the last few years as the government has continually pushed forward its projections of returning to balance.

Australia’s gross general government debt has risen from around 10% of GDP in 2007 to around 37%, and may top 40% in the next two years. Australia’s net government debt is lower at around 18% of GDP. It has blown out from a net asset position in 2007 of around 7% of GDP. The fiscal surpluses in the early to mid-2000s when Australia was benefiting from the resources boom allowed the government to set up its sovereign wealth fund called “Future Fund” established in 2006, mainly to fund government’s pension liabilities.

These fiscal numbers still look quite good compared to the large developed nations, but they are getting to levels that threaten Australia’s AAA rating, in part because Australia has a relatively high level of household mortgage debt owed to Australian banks that still rely heavily on international financing. The strength of the Australian economy and its finances are highly leveraged to the housing market.

Moody’s rating agency wrote in its research last month that government debt will increase further. It said, “First, subdued commodities prices will continue to weigh indirectly on government revenues through weaker corporate and income tax receipts. Second, broad-ranging measures to raise revenues are no longer being considered while possibilities to restrain spending will be limited by commitments on welfare, education and health expenditure.”

Australian Bank Half Year Reports

The Big banks in Australia also release their half year earnings results; Westpac on Monday, ANZ on Tuesday, National Australia Bank (NAB) on Thursday and Macquarie on Friday. CBA releases its earnings next week (9 May).

ANZ and Westpac announced some weeks ago that they were raising bad loan provisions related to exposure to resource companies and South East Asia loan exposure. The results of ANZ and NAB that are more exposed to business lending than the other two big banks (CBA and Westpac) will be watched closely.

Australian banks remain highly profitable and are the jewels of the Australian stock market. However earnings momentum has slowed, bad debts are rising and steady dividend payment polices are under threat. (Dividends in the spotlight as bank profits to top $15 billion – AFR.com)

Somewhat higher bank lending rates over the last six months

To protect their prized profits and address tougher regulatory capital requirements over the last year, particularly in relation to mortgage lending, banks have raised their lending rates (out-of-step with steady RBA rates) over the last six months. Banks are also reported to have experienced some increase in wholesale funding costs this year and are now more actively pursuing term deposit funding by raising the rates they are prepared to pay. While these shifts are relatively mild, they suggest banks have raised rates to protect their margins, and may not fully pass on a rate cut by the RBA should it be delivered this week.

Tightening Bank Lending Conditions

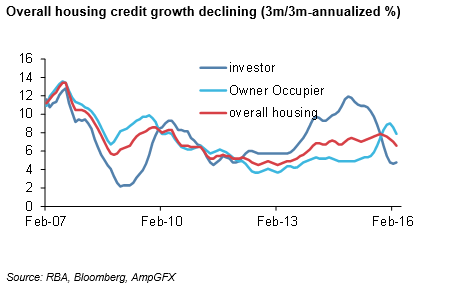

Banks were asked by regulators to slow lending growth for investment (buy-to-let) housing that was running above 10% p.a. up to mid-2015. They have done so applying tougher lending standards and higher rates. More recently news reports suggest that banks have further significantly tightened housing credit for buyers of apartments both domestic and foreign. See our report last week AmpGFX – Elevated and rising risk factors for AUD; 28 April)

This further tightening in credit for housing appears related to evidence of an excess supply of apartments developing and related worries that investors may step back from completing purchases they have made off the plan if prices fall.

As either the chicken or the egg, further bank credit tightening also appears to have followed warnings in the RBA semi-annual Financial Stability Report released on 15 April that, “the tighter access to credit for households could pose near-term challenges in some medium- and high-density construction markets given the large volume of building activity that was started several years ago. These apartments are popular with investors and foreign buyers and any concerns over settlement risk and/or a slowdown in demand for Australian-located property by Chinese and other Asian residents could lead to difficulties for particular projects.” (RBA Financial Stability Review – RBA.gov.au).

While local commentators generally dismissed as sensationalist the report by US research firm Variant Perception released on 22 Feb, called “I know a guy who can get things done”, and was reported in the Australian media as “Uncovering the Big Aussie Short”. The report may have succeeded in pressuring banks to tighten loose practices in the way they handled loan applications from aggressive mortgage brokers.

It appears to be the case that banks have further significantly tightened credit for housing over recent months and this is likely to generate a headwind for the Australian housing market.

As such, the RBA may feel more comfortable cutting rates. The chief concern holding the RBA from cutting rates further over the last year has been the risks to financial stability generated by excessive growth in mortgage lending and rapid growth in house prices.

Sucked-in by the RBA inertia

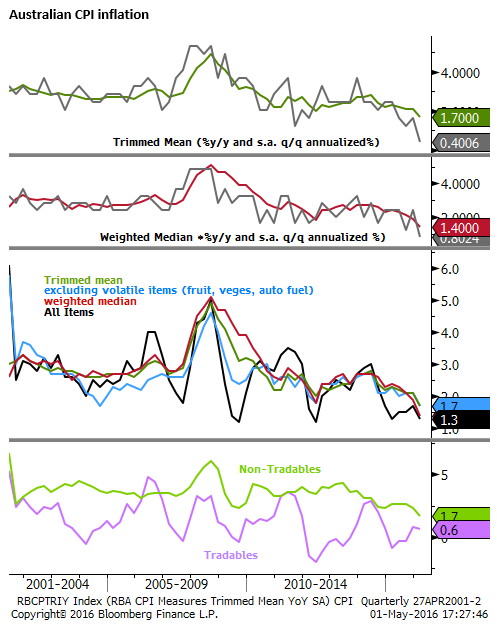

The big news last week was that underlying inflation fell sharply from the bottom of the RBA 2 to 3% target band to well below it. It was 1.7% on the trimmed mean and excluding volatile items, and only 1.4% on the weighted median.

Importantly, the quarterly data suggests momentum is falling, with the lowest readings occurring in more recent quarters, such that the annual measures of underlying inflation may fall further in the next quarter or two. The risk is high that year-ended inflation falls towards 1.5% in Q2 and from there the RBA cannot be confident that it will rise back into its target range within its normal three-year forecast horizon.

It is somewhat remarkable then that the majority of Australian bank economists are sticking to a no rate cut call this week. Only one of the three big four banks has changed its forecast to a cut.

The local economists appear have been sucked into inertia by the stable rate policy of the RBA over the last year as its Governor Stevens has stubbornly resisted the urge to cut rates as inflation slipped to the low side of his target, banks’ edged up their lending rates late last year, the AUD strengthened and global growth expectations ebbed.

Their arguments for inaction include that further cutting rates may do little to boost non-mining business confidence and may even undermine household confidence. They appear to be influenced by RBA Stevens recent speech to a global audience in New York on 19 April where he pointed to the diminishing effectiveness of monetary easing in major countries (Observations on the Current Situation – RBA.gov.au). There is a sense that the RBA is resigned to low inflation, seeing it as a global phenomenon and perhaps something it should not quickly respond to.

Basically many local economists seem to think it’s just harder to see Stevens doing anything unless he really has to, and the growth data has been strong enough that he can wait. They note that GDP data in Q4 was stronger than expected, with upward revisions to 2015, suggesting the economy was operating close to trend, and employment growth has been sufficient to lower the unemployment rate to a recent low of 5.7% in March from a high of 6.3% around a year earlier.

Scott Haslam at UBS believes rates stay on hold. He said, “Low inflation is more likely telling you about supply side pressures rather than weak demand,” he said. “So it’s a good story: consumers have better purchasing power, and even though nominal wage gains are low, real wage gains are doing better.”

The Australian National University’s RBA “shadow board” thinks there is no need for the central bank to move. Its Chairman said, “The RBA shadow board’s policy preferences have turned mildly more accommodative, although there remains a strong consensus for keeping the cash rate on hold,”

Michael Blythe, chief economist at Commonwealth Bank of Australia, points out there have been a number of occasions since the last rate cut in May 2015 that “demanded” RBA action. He said, “Yes, inflation is running below target,” …. . “But that target has always been described as being ‘fuzzy’ or having ‘soft edges. So the Bank is prepared to tolerate periods of out-of-target inflation.” (Majority still see RBA on hold despite deflation – AFR.com, 2 May)

Westpac’s chief economist Bill Evans also sees rates on hold. The Sydney Morning Herald reported that he says a cut might miss the RBA’s targets and simply add to already high ratios of indebtedness…..The RBA would instead be looking at whether the March quarter inflation surprise changed its longer-term view of the economy…..”We believe the RBA is concerned about Australia’s lack of progress in lowering household debt,”…. “Lower rates would be of little help in boosting business investment, whereas household debt is likely to be the sector of the economy responding to the rate cut.” (NAB first of big four lenders to call May rate cut – SMH, Mark Mulligan, 28 April)

RBA cut the obvious decision

Our thoughts are that the rational decision is most certainly to ease policy and that is what the RBA will do on Tuesday. While economic data last year was stronger than expected and even in Q1 unemployment has eased further, the risks to growth are significant over the rest of the year.

The inflation data are reason enough, but as discussed above bank lending conditions have tightened over six months, and more so in recent months and indeed the last month. As such the financial stability risks of a 25bp cut in rates are less. The banks may not even pass it on in full.

The evidence is already starting to show up in the credit growth aggregates, and was apparent in the data released last week. The RBA April policy minutes acknowledged for the first time that, “Housing credit growth had moderated a little over recent months”. There is every reason to believe that this has continued into April at least.

The April RBA policy minutes that included discussion on the RBA’s semi-annual Financial Stability Report, added that, “members assessed that it was appropriate for monetary policy to be very accommodative.” In its policy press release in April and in recent months the RBA said only that, “it is appropriate for monetary policy to be accommodative.”

The RBA minutes added “very” and it may reflect the evidence it had gathered for the Financial Stability Report that more clearly noted that banks had tightened credit conditions, and recent evidence of declining overall housing credit.

At the time of the April policy meeting the RBA was still reflecting on the stronger than expected GDP released about a month earlier, the day after the March policy meeting, and congratulating themselves for resisting pressure to cut rates late last year. Its April minutes said, “Including upward revisions for the September quarter meant that GDP had grown by 3.0 per cent over 2015, which was stronger than forecast in February. Members noted that this outcome was broadly consistent with the improvement in the labour market observed over 2015. More recent data had suggested that the Australian economy had continued to grow at a moderate pace in early 2016 and that activity had continued to rebalance towards the non-mining sectors of the economy.”

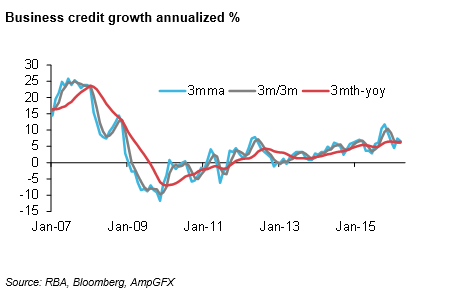

The RBA was reasonably confidence that the recovery in non-mining business activity was building and thus it did not need to support growth. However, more recent data suggests that activity may be patchy or losing momentum. Retail sales disappointed in February and was soft over three months since December. Business credit growth, seen as a strong sign by the RBA over the last six months to February, fell back in March and has not been all that consistent. Given the increasing pressure on banks to control rising bad loans, confidence in a further upswing in business credit may not be as high.

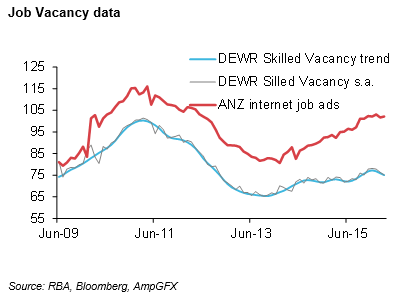

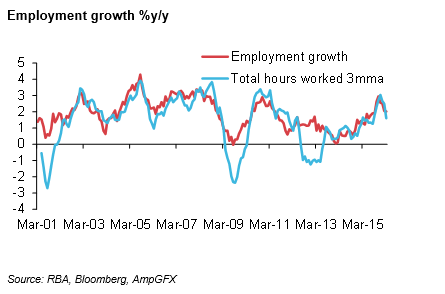

Employment strength has been a virtue for the Australian economy, preventing RBA policy easing. But a look at recent vacancy data suggests momentum may have ebbed.

Total hours worked and employment growth themselves have come of the strong peaks they reached at the end of last year.

Each of these indicators do not argue for a change of policy, but they do suggest that momentum in the recovery is fragile and the RBA needs to be on the lookout for a need to ease policy with low inflation.

Certainly the recovery had more momentum than generally perceived last year, but confidence that it has continued into 2015 should have eased somewhat since the previous policy meeting.

Add into the soufflé that inflation is much lower than thought and may be losing momentum and the evidence that bank credit conditions have tightened more significantly in recent months, and the case for calmly leaving policy on hold falls flat. The case is clear, the RBA should cut rates this week.

Timing a rate cut now, rather than waiting would be fortuitous; it might hit the AUD at a time when it is more vulnerable, and help weaken the currency, something the RBA would like. It would look decisive against the steady policy decisions last week by the Fed, BoJ and RBNZ, it gets on with the job rather than leaving the market guessing what will move the RBA, and provides the RBA a basis to keep forecasting inflation in its 2 to 3% target band towards the end of its three year horizon in its quarterly statement on Friday.

As the economists at the NAB said, “[The] RBA remains an inflation-targeting central bank, so faced with this new lower inflation forecast it now seems likely that the bank’s board will vote in May to take the opportunity to provide some slight further assistance to the Australian economy and so potentially help lower the unemployment rate more quickly than previously forecast,”

Others predicting a cut are JPMorgan, Macquarie, HSBC, Goldman Sachs and Capital Economics. Sally Auld at JP Morgan who is calling for a second cut in August said, “There is enough signal – rather than noise – in the last couple of inflation prints to convince the RBA that the disinflationary trend is genuine, and moreover, has not stabilized.”

Goldman Sachs Asset Management’s head of fixed income for Asia-Pacific Philip Moffitt, one the most astute and experienced Australian and global bond investors, said that although it would be reluctant to move on the day of the federal budget, the RBA might feel compelled to make a pre-emptive strike.

He said, “The low core inflation rate, the negative headline inflation rate and the relatively strong currency – all those things combined – puts the RBA in a position that they don’t want to deal with, but they have to,”

“The fact that we’ve got core inflation at 1.5 per cent – not 1.9 per cent or 1.8 per cent – makes it necessary, we think, for them to move ahead of market expectations, rather than lag expectations.”

Allan Mitchell, the AFR Economics Columnist and RBA watcher said in his first take on the inflation data last week that “If the Reserve Bank is inclined to cut interest rates but is hesitant because of the election campaign, it now has the perfect excuse.” And, “if the RBA concludes that it is very likely to want to cut the cash rate between now and the election, now might be a good time to do it.”